Assassin's Creed Odyssey presents a ‘softer’ version of slavery

Having your cake of ethically aware nuance and eating it too

Assassin’s Creed Odyssey attempts to address the historical nuance of a slave’s status through a series of quests. Its presentations are universally sympathetic. In some cases, they’re downright positive. Scheming cultists who mistreat or acquire slaves are exceptions, not the standard. It’s true that slavery in ancient Greece often operated differently than similar systems in the American South. Unfortunately, since Odyssey is a game about kicking mercenaries twice your level off cliffs and not a history book, we aren’t given the information necessary to understand how and why these differences emerged. Without this context, Ubisoft’s representation of the relationship between slave, master, and Greek culture falls into a Twilight Zone of grinning, apologetic slaves and noble masters that only becomes more disturbing over time.

Just across a narrow strip of sea from the first couple of starting zones are the islands of Euboea and Skyros. Together, they are known as the Abantis Islands. Every major region in the game has a subtitle. Makedonia is designated “Rise of an Empire”, Korinthia is the “Land of Beautiful Corruption”, and so on. The subtitle for the Abantis Islands is “Islands of the Fall”. Where most regional areas have maybe one member of the Cult of Kosmos member, a covert conspiracy whose evil machinations drive the plot of the game, there are at least two on Euboea alone. Taking all of this information together, you might think that there’s something wrong here. Stepping off of your ship, you’ll soon be proven right.

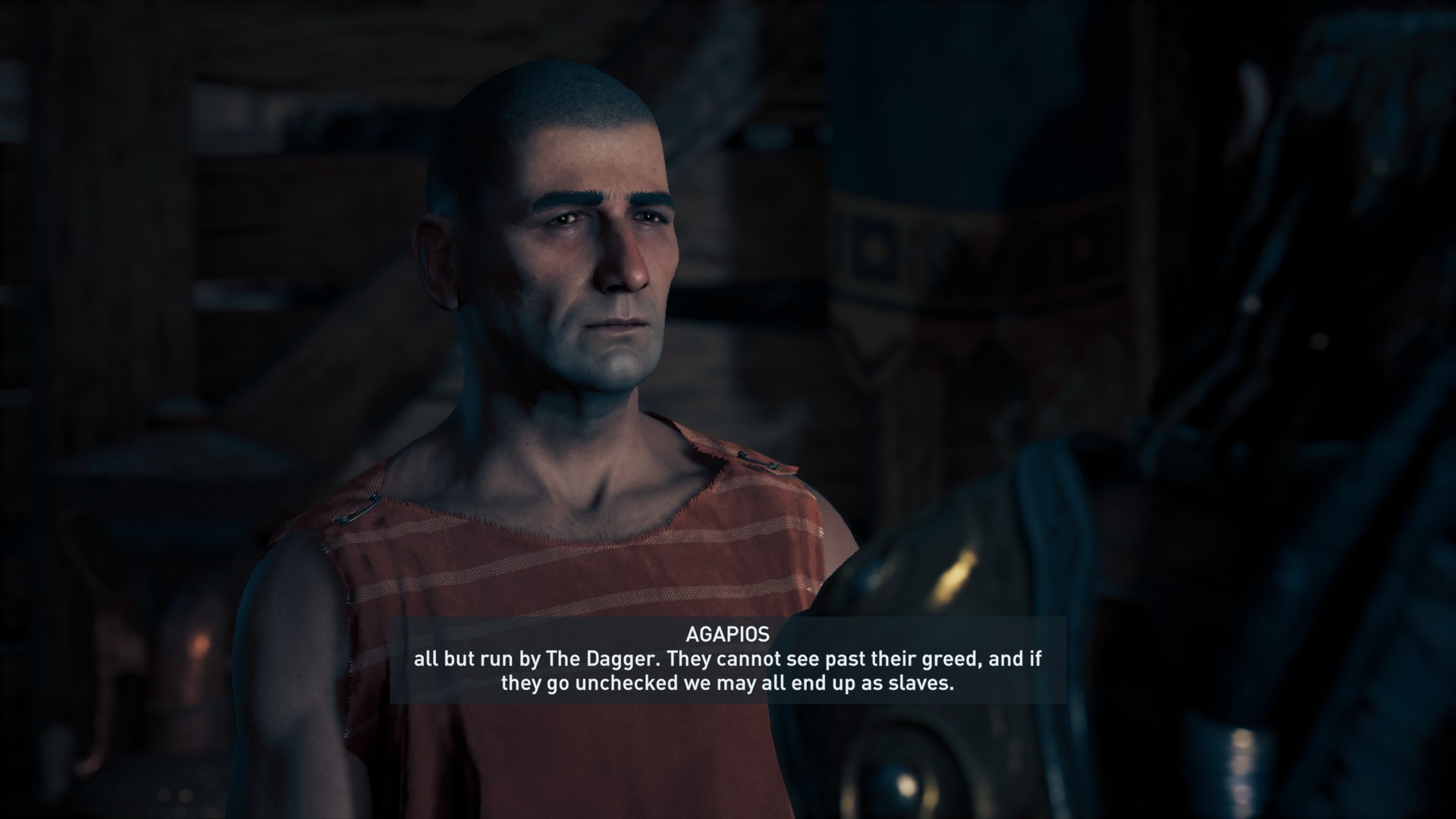

There’s an accountant waiting in a sheltered stall in the port. He asks you to retrieve tax information from a nearby warehouse. Corruption is apparently endemic in Euboea, and he is being barred from doing his administrative duties by soldiers of a mysterious organization called the Dagger - further proof of issues affecting the entire island. Security is light and the mission is an excuse to “complete” the warehouse location, gaining another easy experience boost on top of the quest itself. So you take it. When you come back, the accountant, Agapios, tells you more about himself and his purpose for sending you on the quest. He drops a bombshell: Agapios is a slave.

In fact, Agapios counts himself fortunate. He was sold into slavery as a child, rose to his current station, and now has access to a network of fellow slaves that he believes might contain the information you need to root out the Dagger once and for all.

He asks you to meet him in the slave market to continue your fight against the Dagger’s corrupting power, launching a several-hour chain of quests and events across the Abantis Islands that almost always seems to tie back into slavery.

The slave market isn’t far away, but as I jogged over, I was struck by the grim reality of what I was stepping into. I was going to a slave market. For quests. And loot. I stood still for a moment, meters away from my mission objective, listening to the surprisingly broad range of slave auction dialog recorded for the space. One auctioneer claimed that he won’t split a husband and wife currently being sold. You aren’t just buying service, he argued: you’re buying “family”. It sounded like the clearly disingenuous patter of a grimy salesman looking to get a bigger paycheck, which, of course, it was.

This is where I began to realise that Ubisoft wished to have its cake of ethically aware nuance and eat it too.

On one hand, Assassin’s Creed Odyssey uses slavery as a shocking, nefarious “s-word”. You’ll meet a chortling ass of a man, threatening to sell off the performing children cared for by a couple managing the local theater. He forces you to choose between this couple in a twisted game where one must die, before you finally have a chance to shove a sword through his throat.

Members of the Cult of Kosmos are described in similarly broad, menacing terms, their relationship to slavery used as irrefutable proof of their evil so you can feel appropriately justified in killing them.

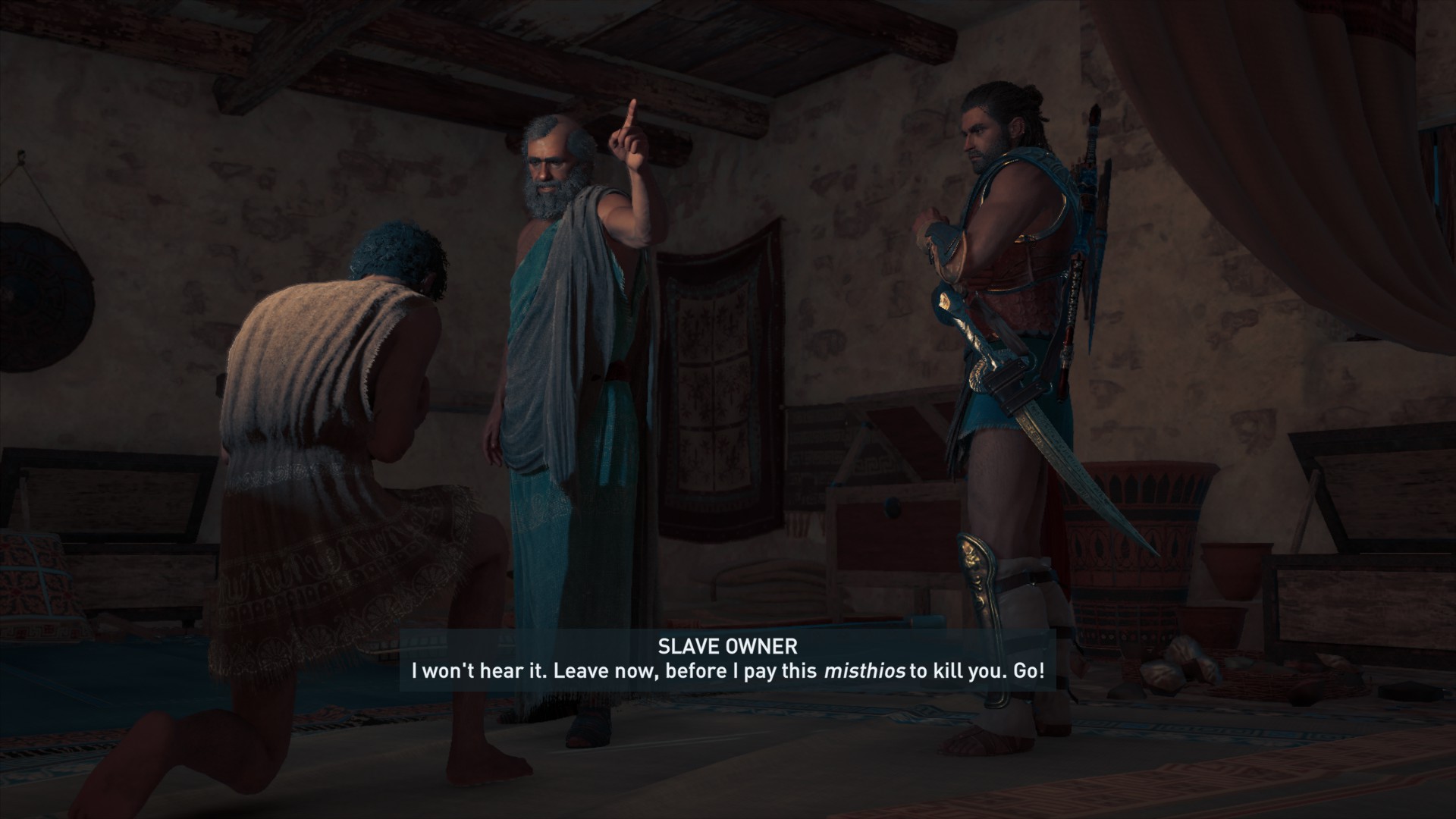

On the other hand, a quest on Skyros leads you to meet a slave who asks you to tell his master that he’s responsible for a recent crime committed in the home. If you do, he reasons, he can apologize to his master, and use it as an excuse to extend his service in atonement. Like Agapios, he describes the fulfillment and safety he feels as a slave — a life he wishes to keep, despite the upcoming date of his freedom.

The slave’s clear desire to remain enslaved makes it all the more heartbreaking if you go along with his ruse. His master throws him out of the house for disloyalty, never knowing the depths of feeling the unnamed slave held for his service.

If you go against the slave’s initial plans, your character instead clears up the misunderstanding directly. The result is an emotional reunion between master and slave that feels uncomfortably one-sided.The fawning slave, hesitant to even tell his owner he wishes to remain enslaved, and the apathetic owner who accepts the service but in a slightly different timeline would have easily cast him into the street.

The one example shown of a former slave, on an island ostensibly focused on the consequences and complexities of Grecian slavery, is a mess. Her tattered clothes and traumatised paranoia frame every line of dialogue. It’s a particularly stark contrast next to the well-fed, dignified, fulfilled current slaves seen elsewhere. You have an opportunity to help her by giving her 50 drachmae after your mission with her is through. For comparison, that’s less than the earnings for selling a single sword. Then, you serve out some platitudes about freedom, as she lays the credit for her now bright future at your feet.

This grand end for such comparatively small effort typifies the approach of the islands to slavery. Balanced on the razor edge of criticism or “not all slavery”, and tipping through lack of overall context.

Slaves across history have inhabited a variety of situations. Some could buy their freedom, others could not. Some could own land, or even operate separate businesses from their owners, while others were property. Bought, sold, and ripped from family units like so much cattle. In the United States, African American slaves would be considered to be 3/5ths of a human being — for tax purposes. This discrepancy in treatment over time and cultures makes sense. Respective positions, and enforced distinctions between classes, reflect the true values and beliefs of the slave master, as well as the society approving or disapproving their actions.

My concern, then, isn’t that slavery is presented positively in the game. It’s a valid and even appreciable angle to at least display. Loyal slaves, slaves who wished to stay with a family before or after being freed, and slaves that were well-treated indeed existed. The problem with Assassin’s Creed Odyssey’s depiction is that we aren’t told that this is a difference from other systems in the first place. It’s taken for granted. We have the what (slaves satisfied with their lot in life) but not the why. Without instances of slaves attempting to run away, for example, or voices conflicting with the heavily positive message of the islands, increasingly confusing, problematic conclusions can be drawn. That THIS is how slavery actually worked, everywhere, at all times. That it was a universally better life than a slave (or former slave) could have otherwise. That maybe, just maybe, slavery was a good thing for everyone involved.

Assassin's Creed Odyssey, an otherwise beautiful, well-considered game, tries so hard to show another view of slavery that it forgets to build the scaffolding necessary to support it, let alone set it apart.

I finished the questline for the island at 2 am. I couldn’t stop playing until it was over, until I figured out what the hell the game that I loved so much was trying to say with… this. Agapios, the trusted slave accountant, was dead. Killed by his brother Kingfisher, who turned out to be the leader of the Dagger all along. The camera panned onto the vast expanse I had supposedly saved, a soft fanfare playing in the background. Looking at the lights shining through trees across the dark inlet, this cinematic cap made me consider what I had actually done in my five hours on the island.

I killed some people. I watched others die. I reunited a slave with his master. I threw the equivalent of a couple of bucks at a freed slave, for what good that would do. And I felt fear. The fear of a black man in a racially divided world, watching a critical topic associated with his cultural and ethnic background be presented with uncritical, ambiguous contentment on the part of the enslaved. Fear of how the simplified depiction of slavery presented by a game I genuinely love might be bent out of shape to perpetuate harmful views, consciously or not. Fear that the concern scratching at the back of my mind in this gorgeous, dramatic landscape will follow me to the next island.

And the next.

And the next.