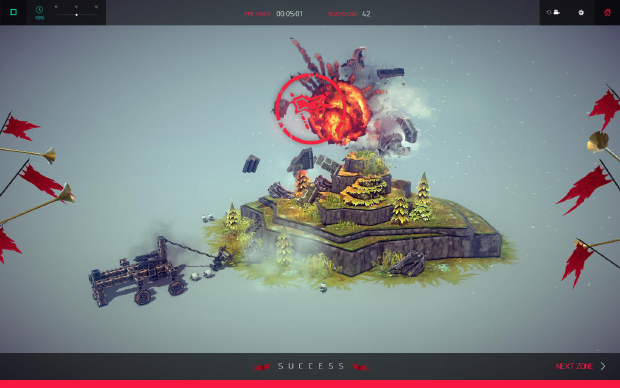

Premature Evaluation: Besiege

Cannon Fodder

Each week Marsh Davies hurls himself at the colossal walls of Early Access and comes back with any stories he can find and/or soaks the earth with the blood of his fallen foes. This week he is catapulted into Besiege, a beautiful, physics-based, build-your-own-ballista game.

Dr Blam is a killing machine. He does not have a medical licence. What he does have is a trio of metal braziers mounted at one end of a large wooden frame, each cupping an oversized explosive ball. The braziers are also attached to springs, stretched taut and fixed to armatures at the other end of the frame. Press a button and the braziers explosively decouple from their moorings while a set of three pistons gives them a little bit of extra lift, the springs contract, and the braziers twang upwards and forwards, slinging their contents in a long arc. Most of the time they even go in the right direction. Dr Blam is not really interested in surgical precision, but if the patient under his tender administration is a castle or a flock of sheep, then a messy lesson in anatomy is guaranteed.

The good doctor is just one of several badly named, haphazardly constructed devices I have designed across the course of playing Besiege’s robust, generous and joyous alpha. Each of the levels in its campaign presents a different challenge, requiring you to modify your machine or build anew. Some levels require your contraption to be highly maneuverable, to weave between explosive mines, or ascend inclines. Others need you to fend off ground assaults of pikemen or overly-affectionate sheep. You might be tempted just to cover everything in spinning saw blades, but you’ll have to find some way to maintain mobility amid mounting numbers of corpses. Later, you’ll want to build something stable enough to pluck boulders from the ground with a crane arm, or ascend steps. And after Besiege has taught you specialisation, you’ll need to work out how to combine your designs efficiently, so that you can survive a hail of arrows, kill the archers and still be nimble enough to weave up a steep and narrow path.

My solution for that, by the way, was to redesign Dr Blam to self-amputate. As soon as his barrage was underway, another button would decouple the cumbersome ballista apparatus, allowing the core of the machine to drop out and skitter away up the hill. But skittering is easier conceived of than done: of all the challenges that Besiege lobs at you, simply driving is the hardest. A sensible-looking steering mechanism will often successfully permit a tight right turn, but, despite appropriate levels of symmetry, the vehicle will sometimes strafe diagonally rather than turn left. Besiege has a few such physics quirks to iron out. Even Dr Blam immolates himself as often as he successfully looses his load, and while that is admittedly a fault of his slingshot design, its curious that the results are so variable when the same conditions apply on each button press.

That’s really just a quibble, however: working around such issues is no hardship when construction and execution are such a joy - methodical and chaotic, respectively. And, regardless, the simulation is consistent enough to make the central task of planning and building a bespoke problem-solving siege weapon a valid and engaging challenge. The tools to do so are powerful, plentiful and neatly arrayed, allowing you to quickly clunk components into place, rotating or mirroring them with hot-keys.

Comparisons with Kerbal Space Program have been made, but Besiege is a little less technically demanding, probably because it’s largely dealing with 12th century technology employed for mass sheep disassembly. It’s not rocket science - but it is definitely some sort of science, bouncily caricatured though the physics is. (What do you think Dr Blam got his PhD in? It wasn’t the humanities.) Besiege has a rich enough menu of components to allow you to build unassailable tanks, octopedal walking dreadnoughts, or even unleash a barrage of bombs from the skies with helicopters or planes. The missions of the current campaign don’t yet demand much more than Dr Blam’s dubious credentials, but a sandbox environment filled with hazards and other squishier, crumblier things encourages you to experiment with the full mechanical repertoire. And the community has certainly done that, producing machines that exceed what the developers considered possible within the game.

It’s also really bloody lovely to behold. I like everything about the way it looks: how the environments fade away into whitebox design space, the soft lighting and stylised simplicity of the world’s objects. Pike men and sheep don’t animate so much as jiggle along the ground - like tiny puppets, manipulated by unseen hands. The UI is weak-at-the-knees beautiful, elegant and unintrusive but with the occasional characterful flourish: mission completion is heralded by Gilliam-esque trumpets and pendants thrusting into the screen. Sonically, too, it is hard to fault, from the thunk of an arrow burying itself into your catapult’s wood to the ambience of birds twittering, cowbells tinkling and the babble of water. Beneath the environmental sound is a sparse and ethereal music that is somehow just right - all the better for contrasting so sharply with the flippant bloodletting of the game in action.

There’s already a good deal to Besiege - its modest campaign lasts 15 levels, and a handful of hours, but I’ve spent a good deal longer just futzing with different designs and trying to get a plane in the air that doesn’t immediately flip end-over-end. Locked islands from the campaign select menu suggest the amount of content multiplying by five come final release, and the devs promise more components are on their way, allowing for yet more elaborate contraptions. It’s rare to find a game on Early Access this confident and competent. I’ve already had my fiver’s worth of fun from Besiege, but even if I had felt shortchanged, its incompletion is, for once, a matter of tantalisation rather than trepidation.

Besiege is available from Steam for £5 and I played version 0.02 on 04/02/2015.

![As Beseige amply demonstrates, many siege weapons were as much a hazard to their operators as their targets. The petard, for example - a hand-delivered conical breaching charge - was so dangerous to deploy that it became a macabre idiom: “to be hoisted [i.e. blown to fuck] by your own petard”.](https://www.rockpapershotgun.com/images/15/feb/besiegepe4.jpg)