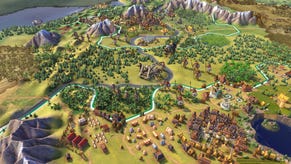

Bold Steps, Cold Wars: Civ VI Diary Part Three

Beyond the sea

This is the third part of a Civilization VI [official site] diary, running from the beginning of recorded history to the atomic age and victory (?). Part one is here, part two is here.

There's something special about taking a first trip over-seas. Whether you're a child or teenager taking a vacation away from your homeland for the first time, or the leader of a nation sending explorers out into the wider world, it's a magical time.

We are Japan. Having established a now-peaceful dominance over our neighbours, we craved new lands to occupy. The discovery of cartography gave even our smallest seafaring vessels the knowledge to navigate their way across deep waters and soon we were carving up the fog of war that lay between the world's two great landmasses. What we found when we reached the other side changed everything.

Americans. The place was lousy with them.

Yes, our new world was America (with bits of Greece in the north), but this was not a retelling of the Columbus story. Far from it.

Spotting the plumes of smoke belching out of American factories was the best moment in the game so far. To explain, I'll need to talk briefly about one of my few complaints about Civ VI. It's not a new complaint, it's an old one that I could level at almost any 4X game, and certainly at any Civ. In short, I reached a point where my tech and culture outmatched my local rivals and, like a snowball becoming an avalanche, my forward momentum was increasing and the gap was getting wider.

It's at that point that I spend more time waiting for the end turn button to light up when the AI is taking its turns than I do acting during my own turns (the AI does take more time as the game goes on but I've never found them to be so long that I'm annoyed by the wait). Civ VI is stronger than its predecessors when it comes to the waiting game, never quite becoming a fancy version of one of those clicker games, but being ahead of the pack can be a little draining.

I should mention that I'm playing on Prince difficulty, which is all that's available in the preview build. For my upcoming review, I'll be testing out higher difficulties to see how challenging they are – on Prince, which is the middle difficulty setting, I've found the going fairly easy on the whole. When I reached the industrial era, as Japan, my most dangerous neighbours, the Spanish, were just about entering the renaissance. The poor Romans, who had been hemmed into a small corner of the continent and struggled to expand at all, were barely medieval.

The disparity is, I think, a good thing. For me, Civ is at its best when it uses history as a loose framework rather than attempting to knit its various techs and buildings to approximately the 'correct' entry point. It's alternative history on alternative planets, not a simulation of the real thing. And the rules make abstractions of every piece of technology and cultural advance anyhow. If one player can't fall behind while another one races ahead, I fear there's a rubber-banding effect as seen in racing games. Weak players boosted to catch up, stronger ones having their tires deflated.

Civ has always been linear. That is to say, each civilization in any given playthrough starts at the same point and moves toward an ending. There are various victory types, and the civs are increasingly differentiated by their special traits and unique buildings/units, but everyone still starts with a settler, creates a single city, and then begins the race through history.

This time around, there's more room to spread out and diversify at any point during the race. That's vital and it's what might make this the best game in the series (currently, I'm not quite sure if I'd still go for IV over VI, but it's close). A civilization that favours artistic pursuits will have at least one city that's unlike anything owned by a warlike bunch, and the smokestacks that polluted the American skyline were an immediate tip-off that I was probably encountering my first industrial society. I don't mean 'industrial' simply in terms of the era they'd reached but in terms of the productivity they'd pursued. Though Washington seemed a city of culture, the land as a whole was an ideal of Blake's dark Satanic mills.

There were other civilizations scattered around the island, and lots of city states that were under Teddy Roosevelt's protection, but the Americans were the clear stand-out. Like my own people, they were dominant among their neighbours, the biggest kids on the block, and I was excited about the rivalry that would occupy me for the next few centuries.

And that's why my trip overseas was an unqualified success. The new world was full of promise. America was my Blackpool

I should explain. When I was a tiny Adam, my granddad used to drive us to Blackpool, which (for those who don't know) is a town in the northwest of England that lives up to just about every stereotype of an old-fashioned British seaside holiday spot. There's the Pleasure Beach, a theme park that has some brilliantly engineered rides but can't quite rise above the games of chance and bone-shaking constructions that feel like its most honest face. There are the piers, where relics of a bygone era tread on relics from a bygone era, and there are the shows, where shuffling, dusty ballroom dances and ribald humour are the order of the day. It's a bit like the internet, except with stag parties instead of trolls and double entendres instead of pornography.

As we drove down the motorway toward the land of saucy postcards, my granddad would always make the same challenge: whoever spotted Blackpool Tower first won a sweet. The sweets were kept in a tin that only emerged from the dashboard on special occasions – there were other treats and snacks in the car, but the tinned sweets were the best of all, made so by their rarity.

And so we'd squint and lean and peer, my sister and I, hoping to catch the first glimpse. The adults in the car pretended to play along, occasionally pointing at a tree or high-rise and exclaiming loudly that they'd won. Then the feigned disappointment from them and fresh encouragement for us.

It's not really possible to squint and lean and peer when you're moving a ship across the sea hex by hex, turn by turn, but the farther out my explorers travelled, the more excited I became about what I might find. Sweets and saucy postcards. Finding new civilizations at a relatively late stage of the game is one of my favourite Civ moments – seeing how they've developed and how they compare to my own empire is always fun.

With the people that you meet in the early stages, it's hard not to measure their progress through the eras alongside your own and Civ's race to victory is apparent. But those first meetings mid-way through a game shake me out of that mindset and I see nations as distinct entities that have evolved along paths that I can't directly trace. They're not competitors, for a few turns at least, they're part of the texture of the world.

And so it was with America. A monstrous factory of a nation that had forged alliances with its neighbours through fear. It didn't boast mighty armies or a powerful navy, but if the strength of its industry were turned toward military matters, it'd be capable of overwhelming me in no time.

Thankfully, Roosevelt's unique agenda, the prime driver for his behaviour, worked to my favour. The Big Stick Policy has him act aggressively toward anyone who causes trouble on his own continent, but he's fairly passive if you're killing people on the other side of the world. A true isolationist. That's why I decided that the most sensible route for Japan, as we hurtled toward the Modern a few centuries ahead of time, would involve the creation of a Union. A Union of Councils, or Soviet Union if you prefer.

That meant the people of my own continent would have a choice: to join Japan in a grand alliance or to join Japan as conquered serfs. Thanks to my scientific and cultural advances, I could conquer at least two of my neighbours using a colonial war casus belli – they were so primitive in comparison that the diplomatic cost of declaring war was negligible. It's in these rationales for war that diplomacy shines in Civ VI – while I find the general process of negotiations too repetitive, creating the ability to find loopholes for conquest is an excellent addition.

The state of the world was set. Two superpowers, nodding politely across an ocean. It was either a cold war or a frozen friendship. My heart was still fixed on a tourism victory and if I could conquer America and use it as the factory while Japan continued on its path toward landscaped perfection, that would be just fine.

An ending was in sight. There was fire and blood between our industrial leisure and the paradise I hoped to build, but I reckoned I could begin and end the war on my own terms.

I was wrong.

You can read the other entries in this series here – our final review of Civilization VI is coming soon.