How Hades plays with Greek myths

Hell to pay

When Supergiant Games started to make Hades, their Roguelike action-RPG, they had plenty of experience making narrative games. Across Bastion, Transistor and Pyre, they’d found they were pretty good at telling stories. But in a Roguelike? And what’s that? They intended to put Hades in Early Access? Could they ever fit with the kind of rich characterisation and storytelling that made Supergiant’s name?

“We were really curious to see if narrative could fit into an Early Access experience,” writer and designer Greg Kasavin tells me. “And it turns out, it immensely benefits from it.” I have to agree. Hades’ Sisyphean-twitch-action, in which you take repeated runs through the Underworld in an attempt to escape your hellish dad, is brought to life by a setting within the rancorous interplays between the gods of Greek mythology, and dynamic story design which responds to your progress.

Hades was founded in the embers of Pyre. This sports-cum-strategy game, which was released in 2017, is wrapped inside a choice-driven visual novel about a bunch of fantasy jocks who have been banished into purgatory and must travel the land to play other crims in the hope of cleansing their souls. It was well received, but I get the sense that Kasavin is a little disappointed with some of the creative decisions he and team made for it.

“Man, we did all that work to create truly branching open-ended storytelling, but Pyre feels like a game that you’d only play once,” he says.

Pyre may as well have been just as linear as Bastion and Transistor. But the studio loved the narrative design they created, so they decided their next game would refine and be in a genre much better suited to it: the endlessly repeatable Roguelike.

“Whatever form the narrative would take, it was meant to make moments of story that’d intersect with the action and help contribute to memorable runs,” says Kasavin.

Hades’ Greek mythology setting came soon afterwards, along with the idea that players would wield powers defined by various gods, who’d also be characters. At first, though, the game was going to be set in Minos’ labyrinth of the minotaur.

“The labyrinth was going to be a shifting environment, a maze, different every time, and at the centre of it was a minotaur you have to hunt down,” explains Kasavin. It sounds so fitting! But Supergiant soon found they were struggling to fit the narrative design into it and to develop an interesting protagonist. That’s when Zagreus came along.

Hades’ gods and heroes might speak in modern language and provide a backdrop to a hack and slash game, but you can feel it’s all underscored by Kasavin’s real passion for Greek mythology, which began when he was a kid. As the project kicked off, it saw him reading Siculus, Ovid and Hesiod, writers he’d never read before, along with several different translations of the Iliad and Odyssey.

“I ran into this detail that there’s this little-known god called Zagreus who, according to some, is a prototype of Dionysus, but there’s also a shred of evidence that he might be the son of Hades. Like, woah! What’s that about? Then I researched Hades more, and it turns out there are very few stories told about him.”

Zagreus was a perfect subject: the lack of stories about him and his father gave Kasavin space to imagine new ones, and the repeating Roguelike structure slotted neatly into the idea of him running away after a blow-out fight with his dad, then failing and finding himself home again.

“And it seemed really funny! These slapstick failed attempts to get away, and your dad just makes fun of you and says I told you so. We were interested in that light-hearted tone because I think that the Roguelike experience has a slapstick quality. One moment in Spelunky or FTL you feel on top of the world, and then you make some bone-headed mistake and throw it all away. You feel clumsy and stupid and you hopefully laugh at yourself.”

From there, the dramatic role of the gods became clear. They’d be a big dysfunctional family unit, fighting and bickering and using their support of Zagreus against each other. “You can think of them as a powerful crime family, because there’s no one who’s going stop them from doing whatever they want,” says Kasavin.

In the mechanics of the game itself, the gods lend Zagreus their powers – boons – for each run through the Underworld. Zeus is about lightning, Poseidon about water. Hermes is about speed, Artemis about ranged attacks. Their iconic nature gives players an intuitive understanding of what they’ll broadly do – “we were drawn to having Hades be more straightforward,” says Kasavin – a reaction to Transistor’s more opaque powers, which required players to work to understand them.

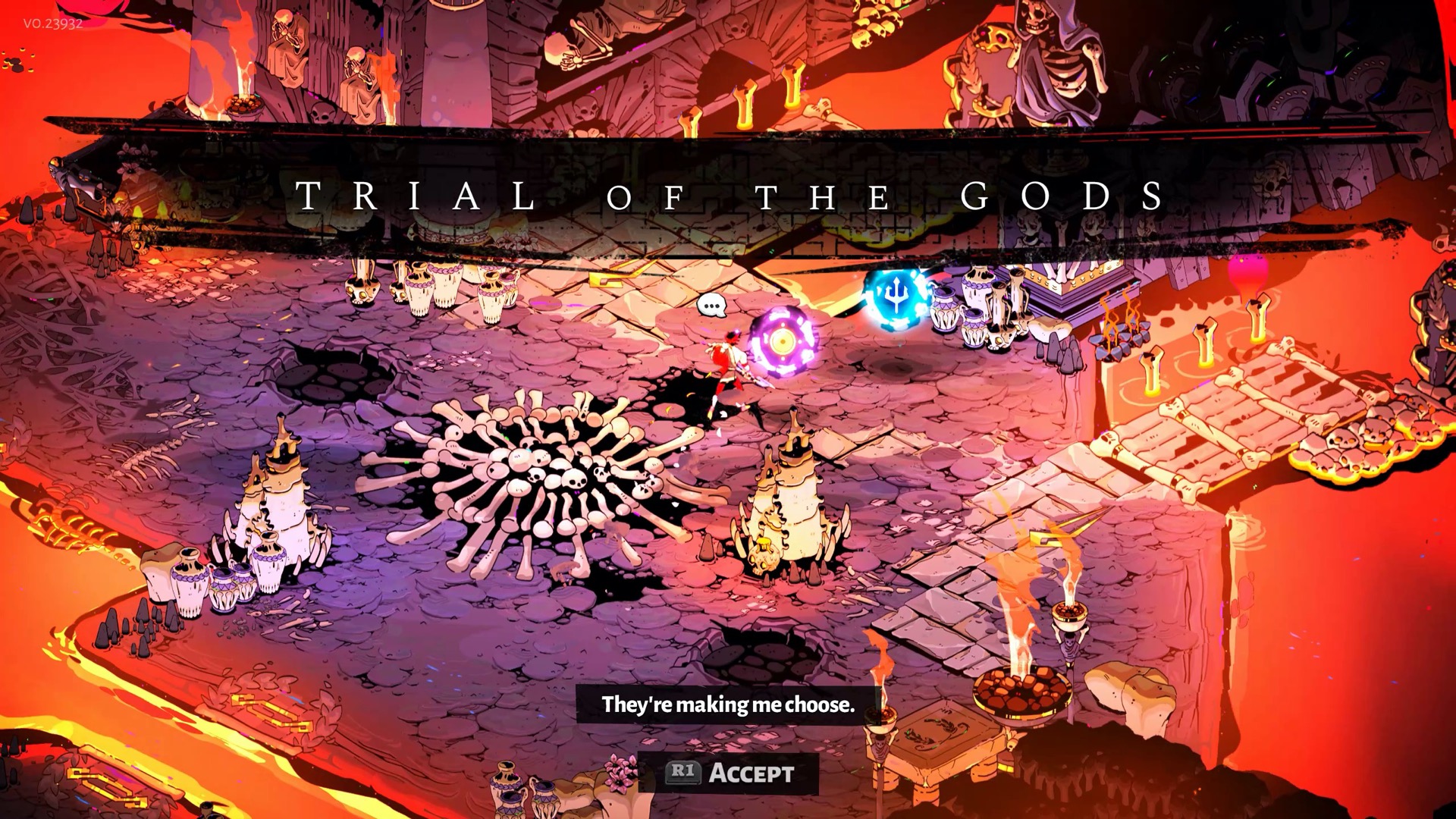

The idea of competition between the gods led to features such as the Trial of the Gods rooms. “We had to find a way to get the gods to interact with each other and express their displeasure with you,” says Kasavin. “They’re fickle, right? They love you one moment, they hate you the next.”

So in the Trial of the Gods rooms, you get to choose between two gods’ powers, and the god you didn’t choose then punishes you by turning monsters on you. “It’s a fun little change of pace, where you get to see another side of their personality and pick up an extra reward if you take the heat.”

The most recent divine addition to Hades is the god Demeter, and by gosh, Kasavin is glad she’s in, even though she’s not exactly one of the star gods. “Demeter is the goddess of agriculture,” he says. “You have a guy who can strike people down with lightning, and you have someone who grows wheat. So that sounds awful.”

But Demeter has added a rich new dimension to Hades’ storytelling, since she’s at the centre of the most vital myth around the Underworld. She’s the mother of Persephone, who was abducted by Hades. Demeter, enraged, finds out where she is and gets Zeus to force Hades to let her leave the Underworld. But on the way out, Persephone eats six pomegranate seeds and as a result has to spend half the year in hell.

“That, for us, is woah. She’s a mother who’s lost her daughter and she’s mad. She’s past the initial stages of grief and now there’s this bitterness. So she’s like, alright, fine, you took something from me, so you’ll have winter. It felt so clean.”

But even then, she nearly didn’t make it into the game. “From a writing standpoint, I’d love for Demeter not to be in the picture, because the story’s complicated enough as it is. But then, months into development, I felt very cowardly about that. Wait a minute. Demeter is important, this is a story about family. And furthermore, it feels shameful that this character hasn’t been rendered in an interesting way, to my knowledge.”

And besides, the bringer of winter presented an opportunity to finally add ice powers. “We’re making a fantasy game and still love Diablo and all that, and we hadn’t found an excuse for freezing powers.”

Aside from the theming, though, the real magic in Hades’ narrative lies in the way it responds to your actions and progressing storylines, despite being set within an endless cycle of dungeon runs.

“Reactivity has always been a goal of our narrative design, to have those moments where you feel the game is paying attention,” says Kasavin. And Bastion and Transistor are well-known for the way your character comments on what’s happening. “Those moments in games are so good, so we try to create as many as possible in the hope players can experience them.”

But Bastion and Transistor are linear games which gave Kasavin lots of control over how they did it. “Hades is completely different. We have no idea, apart from a couple of moments, how things are going to be sequenced and how they unfold for a player.”

So Hades uses a system which looks at what’s happening and sees whether it matches a huge list of events that Kasavin has written – enough that it’ll take tens of hours of play until they repeat. “So, hey, you just found Zeus while you were about to die. We have an event where Zeus is like, ‘Man, you’re in terrible shape, let me see if I can help you.’”

Some events are one-off reactions to situations, some are part of storylines, and the game figures out which to show, but Kasavin has some influence over them because he can weight conversations in importance.

For example, you might run into Eurydice during a run. Then, back at the House of Hades after the run’s over, you might find her husband, Orpheus, who’s trying to rescue her from the Underworld. When you talk to him, the game will play a conversation in which Zagreus says he saw Eurydice and Orpheus asks you to give her a message if you see her again. Then, when you see Eurydice, the next conversation in the chain will play.

The story between Orpheus and Eurydice also illustrates the way Hades ties storylines between a run and the downtime after it; the chance to see what’s new back at base and to progress storylines eases the frustration in dying. Will Achilles be back? What happens when I give Megaera this nectar? How’s bad-dad going to mock me now?

“It was an explicit goal of our early development, to take the pain out of dying and having to restart. If the whole game is structured around dying and restarting, then we had to make sure the moment of death isn’t about rage-quitting. You have to be compelled to explore further and feel the time you spent wasn’t a waste of your time.”

It’s exciting to play a game that marries authored storytelling, a strong theme and dynamic interactivity so seamlessly. But Hades’ real success is that when you’re playing, it’s easy to forget just how progressive and clever its narrative design is.

But it seems it’s inevitable that Kasavin would shift from the linear stories that built Supergiant to non-linear ones that make the player the driver. “There are much more efficient and probably better ways to tell linear stories than through games. I’d try to write a book or something,” he says. “But we’re making games, and we have to take advantage of what’s unique about the medium, which is its interactivity.”