Wot I Think: Offworld Trading Company

Two invisible thumbs up

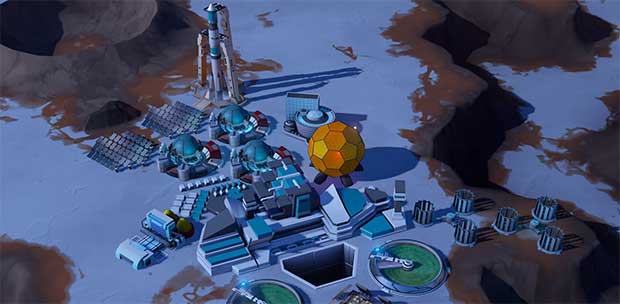

Offworld Trading Company [official site], the new game from Civ IV lead designer Soren Johnson and his team at Mohawk Games, is a strategic simulation of a sci-fi Martian economy. It's also one of the smartest strategy games I've ever played.

Money is no object. That's the most important lesson I've taken from the hours I've spent running a corporation exploiting the raw materials of Mars. It's a phrase that I mean in a very literal sense and cuts to the heart of the brilliance of the game's design: it's a game about making money in which the actual amount of money you have doesn't matter anywhere near as much as the flow of cash and resources.

Offworld Trading Company treats money as ephemeral. Values change constantly in the dynamic market that is the game-space. Mars may be the landscape on which you're constructing the tools of capitalism, but the entire corporate conflict plays out in the markets. Just as many RTS games are played on the minimap, Offworld is played in the numbers at the side of the screen. The genius of the game is in making the manipulation of those markets comprehensible while never allowing them to become predictable.

And yet they're entirely predictable. Everything that you and your opponents do causes the figures to shift in a sensible fashion. Build a production chain to make glass or computer components and you can flood the market with the end-product, causing prices to plummet. Create a monopoly on one of the resources necessary for survival on the planet and you can hoard the fruits of your labour (or your labourers' labour, I guess), forcing everyone else to ship the stuff in from off-planet at great expense.

You're always making choices, every second that you play. There are ways to interact with other players directly through purchases made on the black market. These disrupt and interfere, cutting off sources of revenue, stealing resources or manipulating the market to present false figures. All of that comes later. The most important decisions are related to the limited claims you're given at the beginning of each game. Looking at a random map, you must decide where to place your headquarters and then secure the first pieces of land that you'll construct factories, solar panels and other facilities on. There are obvious sequences of construction to follow in the early minutes of each map, but to win you'll need to adapt to the situation as it changes.

Everytime you upgrade your HQ, which costs cash and specific resources you'll receive a new set of claims. There are other ways to get them as well, but mostly you'll be working your way up through the game's equivalent of a tech tree, enjoying a brief flurry of expansion each step of the way. The claims system ensures that your corporation can't produce everything – you need to specialise and, crucially, you need to engage in a symbiotic relationship with your opponents.

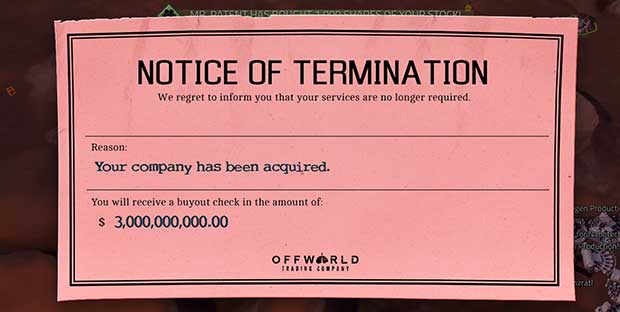

Offworld creates an incredible tension through this forced cooperation. The difficulty of operating on a planet with an unfriendly environment makes the corporations reliant on one anothers' produce, particularly in the early game. They can't thrive – or even survive - without what the others have. To destroy them would be suicidal. You're not trying to destroy your opponents, you're trying to absorb them. The end-game isn't destruction, it's a hostile takeover.

When you're vulnerable to a takeover, the game tells you. It crunches the numbers, figures out that somebody has enough assets to buy a majority holding in your company, and lets you know. Your opponent - the person currently holding all the cards - doesn't get that message. They may have the ability to snuff you out but the game doesn't tell them; the potential victim sees the Sword of Damocles but unless their opponent is paying close attention, they might just see a CEO sitting on his throne.

That goes back to that opening phrase: money is no object. Cash alone isn't always enough and the buy-out might require liquidation of stock. Performing the buy-out might then make the buyer vulnerable to the remaining corporations and will almost certainly cause an upset in the markets that might dangerously upset the balance of power.

Everything that you do has consequences and everything that your opponents do will have an impact on the state of the world. I can't think of another strategy game that is so changeable. To succeed you'll need to be flexible, not just building bigger and better, but willing to change course, tearing down facilities that have been rendered obsolete by market forces and replacing them with something new. The market never stands still but, thankfully, the game does. In the endlessly replayable singleplayer campaign, the world pauses whenever you make a decision, and can indeed be halted at anytime with a push of the space bar.

The entire campaign is like a turn-based variant of the rapid-fire multiplayer game. There's a progression system threaded through the randomised scenarios and it's forced me to reconsider the entire game, having only experienced it in multiplayer for so long during Early Access. When I came to write this review, I asked myself if I'd buy the game just for the singleplayer mode. I would. The multiplayer brings out the best of the systems, creating its own weird momentum through panicked mistakes and elegant deceptions, but the singleplayer takes all of those same systems and creates a slower, more thoughtful experience out of them.

That the economic simulation can cater to these two varied experiences is testament to the intricacy of the design. The core mechanic - the market that acts as a malleable foundation on which every other system is built - is close to perfect.

All this talk of systems (and there's much more of that in my preview) makes Offworld Trading Company sound like an abstract thing, disconnected from its setting. Every element is thematically appropriate though and there's some subtle world-building between the interplay of mechanics, particularly in the implied off-screen asteroid mines that are an essential part of the flow of capital. Mars is a relatively safe and serene place, even when there are horrible weather conditions and pirates buzzing around, and if you focus on the map and manage to filter out the movements of the market for a while, there's a certain tranquility at odds with the cutthroat deals and deceptions.

The score helps - it's the work of Christopher Tin, composer of Civilization IV's Baba Yetu.

Civilization IV - the greatest strategy game ever made - was Offworld creator Soren Johnson's first commercial games as a lead designer. Offworld Trading Company is an entirely different proposition: short-form rather than ultra-long-form, real-time rather than turn-based, sci-fi rather than history. Its surface complexity and basis in economics rather than war and culture make it a less immediately attractive game than Civ, but it's an exceedingly intelligent game.

I haven't even mentioned the different challenges offered by each of the four factions. There's so much to analyse that I could write another couple of thousand words, but you don't need to know everything. What you need to know is that Mohawk have made a game that creates tension and ruthless competition out of a screen of ever-changing numbers. Every victory feels hard-earned and every defeat can be traced back to specific twists in the tale, and in each of its half hour sessions, there are as many twists as in Civ's six thousand years.

Offworld Trading Company is out now.