Free-To-Frag: QuakeWorld's Once-Planned Business Model

Just some old news for you

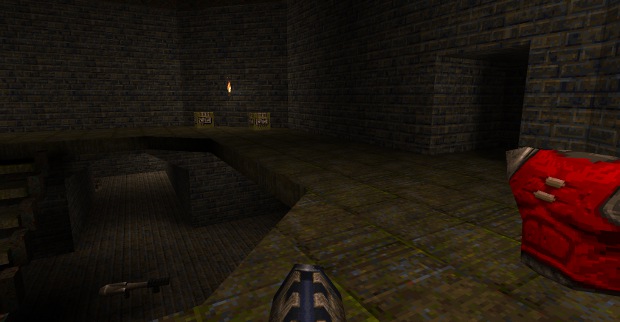

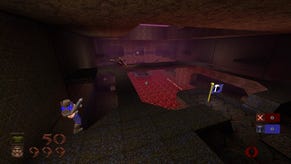

When John Carmack started tinkering with Quake's multiplayer code in 1996, his plans for the QuakeWorld client went deeper than TCP and UDP. Its new netcode made playing an FPS online over dialup not total garbage, sparking the multiplayer FPS explosion, but Carmack had also once intended for QW to be what we'd now consider free-to-play. Though the plans changed and this never happened, I can be endlessly fascinated by scraps of video game history like the time John Carmack thought about selling the right to have a name.

Quake had started building a multiplayer community even before release, with Qtest, and QuakeWorld was to encourage that competition and bragging something fierce. "All frags on the entire Internet will be logged," Carmack schemed in a .plan file update (an awkward precursor to weblogs, using the hilariously-named 'Finger protocol') in 1996:

"You should be able to say, 'I am one of the ten best QuakeWorld players in existence', and have the record to back it up. There are all sorts of other cool stats that we could mine out of the data: greatest frags/minute, longest uninterrupted Quake game, cruellest to newbies, etc, etc."

Quake became a game with big personalities ("Who names their child KillCreek?" I wondered, reading PC Gamer) and plenty of trash-talking. It also connected people to form communities and friendships and all those soft things. That's why Carmack's monetisation idea fascinates me:

"My halfway thought out proposal for a biz plan is that we let anyone play the game as an anonymous newbie to see if they like it, but to get their name registered and get on the ranking list, they need to pay $10 or so. Newbies would be automatically kicked from servers if a paying customer wants to get on. Sound reasonable?"

id did shareware. They made large chunks of their games free to prove the full thing was worth buying. Carmack's idea would give away the pure game side but limit access to what made multiplayer any fun at all: people. Connecting and competing with people across the world, exploring that weird frontier, and expressing ourselves as whoever we wanted to be was so exciting then, and vital to multiplayer. It'd be a mite more difficult without a name.

I've been idly imagining an alternate timeline where free-to-play grew out of weird ideas like this. Popular F2P models focus on the game side, selling boosters, items, and so on. Carmack's idea would have monetised human interaction. Which sounds a bit monstrous when I say it like that. (And stats, sure, all those stats, and the not-getting-kicked-from-servers, but I'm not particularly interested in those.)

In a way, Dota 2's take on free-to-play feels close to this. Valve let everyone play then charge for instant unlocks of cosmetic items. These don't affect the core game, so buying (or not buying) never feels unfair or cheaty, but they do let us express ourselves through our wizard's outfits. As hero looks can range from blind mystic to Cyndi Lauper, it feels unusually personal.

Video games are very different now. Pre-Steam, pre-Counter-Strike, pre-PayPal, Carmack wrote:

"If it looks feasible, I would like to see internet focused gaming become a justifiable biz direction for us. Its definitely cool, but it is uncertain if people can actually make money at it."

At the time, id didn't believe they could. These plans were dropped. QuakeWorld didn't turn out like this. In the end, it was simply (hah!) an updated Quake client for people who'd bought it. QW did launch with basic player rankings, but stopped them after a few months. The first multiplayer-focused id game was Quake 3, three years later in 1999. In 2010, Q3 became the free-to-play Quake Live. Its business model isn't nearly as interesting to coo and poke at.