Set The World On Fire: Fate Of The World

It's a good day for the interview to go live, I think. I've been following Red Redemption's global-future strategy game for a while and now - with its release on the horizon and its name settled, I thought it was time to talk to its charismatic founder Gobion Rowlands, Creative Director/Lead Designer Ian Roberts and MD/Producer Klaude Thomas about Fate of The World. We take in everything from the real science behind it to the gloriously apocalyptic actions you can perform to try and save - or destroy - the world.

RPS: Anyway, top level first. Care to talk about how the game came about from your previous work?

Gobion Rowlands: In 2007 with the help of Myles Allan from the Oxford University Physics Department, we convinced the BBC to sponsor us to make a strategy game called "Climate Challenge" in Flash. Our concept was that you would run Europe for 100 years in the role of president with a mandate to tackle climate change. It had some pretty strict limits - it had to be for over 18s, had to be serious in tone and had to use real world data. This was a chance to make some fun gameplay out of a subject that hadn't been tackled before.

The game was far more successful than we had hoped and eventually around a million people played the game. We also learned that first time through that many players sought to cause as much destruction as possible or went after specific technologies (the path to shiny) rather than play the game 'straight'. I shouldn't have been surprised really - taking the destroyed approach is fun, and also lets you see how bad things might get. We then made another follow-up flash game for education, followed by some unrelated work; but in early 2008 looking around at where the games market was heading with the emergence of a strong indie and serious games movement, we hypothesised that there was a much bigger game to be made there... and we wanted to make it.

RPS: So - what was the next step?

Gobion Rowlands: Two questions kept popping up: Why cover just 100 years and why just Europe, when there was an entire world to play with? We imagined covering the full human drama that climate change will cause - there will population issues, land issues, possibly resource wars, mass migration; a whole range of disasters and impacts, in fact. We also looked at platform. At the time we were having fun playing other peoples Nintendo DS games and wondered if serious games couldn't be made for that? We explored that by prototyping two ideas and quickly realised that what we wanted to do wasn't an ideal fit for the platform. We prototyped something more like Sim-Earth or Civilization, and considered designs influenced by the Sims. In parallel we worked on our business model and quickly realised that frankly as an indie developer the DS was the wrong platform - it is dominated by the big publishers, shelf space is at a premium and the returns per unit make it really tough for a small developer to even recover their development costs.

So we switched to PC, which immediately felt like coming home to us. PC gaming is where I do almost all of my gaming and always has been and is a natural environment for strategy games. Of course they can work on consoles, but then when you consider how much more approachable the PC market is for an indie developer via online distribution channels, well understood architecture, minimal dev kit costs and the cost of goods is much smaller on dvds compared to cartridges and almost non-existant for online sales which is where the market has shifted to.

So that was the genesis of the game that has come to be known as 'Fate of the World'. But coming up with the rough idea was just the start. We are a small indie developer and we wanted to make a PC and Mac title that would take real world climate data, economic data and all sorts of other data and make a challenging strategy game out of it for the commercial audience. We quickly realised that this wasn't exactly regular publisher material, so we decided to try fund it ourselves. Something that at the outset we weren't sure was possible.

We kinda seem to like taking on massive challenges and then adding on some more challenges - but it was the only way we could make this project happen; and I really believe that it needs to happen.

Luckily we met a number of private investors who really understood what we were trying to achieve and gave us the funding we needed. It may sound easy, but it has been a struggle at times. We got some good breaks. That said staying indie was by far the best move for us. Once we had our seed funding we had to get on with the process of designing and making the game.

RPS:: And what's the state of the game now?

Gobion Rowlands: We spent the first nine months of the game getting the underlying model in the game right. That is really a fundamental of any strategy game and before you have that it is difficult for the gameplay to emerge, and this game was using data that had never been used in a game before, so step one was just trying to understand what it was we were working with and the scope of that challenge. That meant we needed a fulltime scientific advisor as well as games designers. We also got onboard a number of key scientific advisors to help us understand the models and data. Then we had to translate those into useful numbers and dynamics for a game. Near the end of that time we started to appreciate the underlying changes that are expected to take place in population and regional development over the next century. We had to create an AI that makes those changes while you are playing: you have powerful drivers changing the playing field dramatically while you play.

We completed core gameplay just after Christmas. This was the stage where we brought together of the different elements of the game for the first time to see what was working and what wasn't. This process showed that we'd not put enough emphasis into the impacts and feedback for the player and that focussed our minds on getting those elements in as our highest priority. Without those you have the framework of the game but no game. Every game requires tension in the dynamics for the player to exploit and receive crunchy feedback. Needless to say early 2010 has been a stressful time for us all, but we came out of it with every element of Fate of the World more clearly defined and with the plan for the schedule all the way to launch. It is those moments in a project where having someone like Klaude (our MD/Studio Head) managing the project is so key as he kept a steady hand on the tiller and got us through.

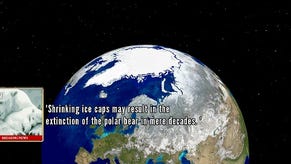

After reviewing all the available options the engine we had opted for Ogre, used most recently by the excellent Torchlight. It has its issues, sure but overall I think you will be seeing a lot more use of it in the future and it fitted our requirements very well. The stage we are at today is integration where we populate the game with the Masterplans, policy choices and the various feedback loops. A huge amount of work has also gone into making the star of the game the globe, and ensuring it features ice and snow cover changes, sea level changes, desertification, forest cover and also the feedback mechanisms for impacts.

Of course the other bit we just reached was the final name for the game. Fate of the World fits the broad scope of the game narrative we are trying to capture, whereas the pre-production title of Climate Challenge 2010 did sound a bit edutainment. Something people were quick to comment on. It can be frustrating from our point as there are a lot of cool things going into the game, and make no mistake it is a game rather than an educational sim. We want to give players power to do some radical things - to explore a range of possible futures based on coherent, believable economic and population dynamics, with the evolving environmental apocalypse biting them as they do it.

RPS: As a matter of interest, how do the Science advisors respond to the fact you're making a game? As in, do you have to work to prove your seriousness, or are people actually much more welcome to the possibilities of interactive games as a way to talk about this kind of issue?

Gobion Rowlands: You touch on an interesting aspect of Fate of the World's production. The first step for us was to ensure that each Science advisor was consciously aware of that core point: that we are making a video game! Spelling that out really clears the air. We have also had to prove our credentials: building those up over several years. For example, we have a science advisor on staff (Hannah Rowlands) to liase between game designers and scientists. Hannah has Oxford degrees in science and physics, and is a graduate of the environmental change masters program, but is also an enthusiastic gamer (lately completing Plants vs. Zombies twice just to get everything). Scientists don't think quite the same way game designers do: you have to work on that.

The scientists we work with are fantastic. Where we find ourselves asking "what does highly technical thing X give to players?" they give us the encouragement and data to make good design decisions. That was one of the things that most surprised me about all our interactions with our academic partners. They want our games to do what games do best - be entertaining personalised experiences that are challenging and fun for the players. For a specific example, Dr Myles Allen, who provided the climate model, pushed us to make sure we included methane as well as CO2, but he did so for game play reasons as well as scientific ones. He pointed out that if we included methane we could include a lot of exciting/scary geo-engineering technologies. That opened up a new set of features for players: who wouldn't want to be able to risk plunging the Earth into an Ice Age, or cause floods of biblical proportions?!

Ian Roberts: There's two sides to it, really. On one hand, games are superbly suited for expressing ideas vital to the subject and in that regard our advisors are very keen. Take the impacts of climate change, you have both the chance of them happening and how much they'd hurt if they did. It's not easy to get a feel for that when reading an article on climate change but a gamer understands this relationship all too well - it's L4D's survivor, as the clock goes up the chance of that tank is greater and tanks really hurt.

Old media like newspapers and tv are terrible at reporting science and regularly confuse correlation for causation. The press reports scientific study as "the tank will kill us all" where a game shows you "the tank will often kill us all if we're standing right next to that car". Our challenge is making a rich enough system (with enough variation) to give us lots of amazing outcomes. The science advisors are great at understanding the degrees of approximation that are both satisfying in play and reasonable representations of the material.

RPS: Games are the best medium for explaining systems to people. Agree or disagree? And why?

Gobion Rowlands: I would say I have to agree, but that is probably self-evident. The thing about a game is you can spend 20+ hours immersed in the game world, exploring all the options and looking to improve your position through score or other character development. It is a profoundly personal interactive experience where you are the star, or at least one of a small group of friends or clan mates, and the game concerns itself purely with you.

In a game we also are free to experiment and to learn by that experimentation in a way we sometimes don't get in the real world. It doesn't matter if you break something, just reload your save and try again. You also can explore the world at your own pace and focus on the things that most interest you. Essentially what I am saying is games thrive on complexity and that is a good thing. Far from dumbing their audience down, I really believe that many games can and do appeal to the intelligence of their players.

For me there is no better format for explaining systems to people.

Klaude Thomas: I think that you can do some explaining of systems using any medium. A movie or TV documentary can explain a system in a way that is easy to digest, a book can present all the graphs and data: it's faster to turn back to a key page in a book, than to find your way to a specific point in a game level. The difference to me is the kind of understanding you acquire. After a few plays of a game your brain gets the feel of how to change the system the way you want it: you get the feel of the levers and relationships. This is a sort of deep, infra-learning. You get the feel of the system wired into you, your organic neural net changes weightings and so on.

But we're only really at the start of all this. Game designers are on a fast learning curve with plenty still to discover about how to make it happen effectively. Our goal foremost right now--with Fate of the World--is stimulation, fun, whatever you want to call it. Entertainment!

RPS: Okay - "a game about global warming" is a high concept people get. But what do you actually do? How do you play? How do you interact with the system? What's your approach - freeform, mission based or both?

Gobion Rowlands: So the year is 2020 and the world has done nothing significant to tackle the multitude of problems facing 21st century society, and then the first impacts strike and the nations create a new global organisation - the World Environment Organisation - and they put you in charge. But your past is murky and your motives mysterious. You can see that we need to tackle these issues, but frankly those are not your goals - they are the obstacles you need to overcome to create the future you want for humanity.

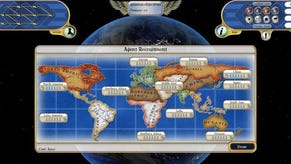

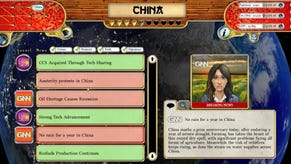

What you do in Fate of the World is through a mix of cunning, strategy and occasionally brute force with 12 global regions to get them to make the changes necessary to survive and prosper (or causing an apocalypse) over the next two hundred years. You interact with the system via the paradigm of playing cards (which unlock other cards, etc), and in response the world changes (the snow retreats, deserts shift, countries go to war, stuff happens).

The approach is a bit of a mix actually. We have a missions structure in the form of the "Masterplans" - things like 'Apocalypse' where the player is given the task of causing as much devastation as possible, the 'Lifeboat' mission where they save just their region and no others, a 'Utopia' (in the sense of Brave New World) where the player has to sculpt their global utopian society, a fun (and I use that term advisedly!) masterplan based on Soylent Green where you need to try and get the global population to 20Bn when the current thinking is that we can support at most 10Bn people, and of course a rise of the machines type Masterplan where we move to a mechanised future.

Mixed in with the missions are the freeform elements in the form of the policies. So the player chooses which missions they want to attempt, but how they complete that task is very much freeform as there are many routes they can take in the policy and tech development. The policies themselves are presented as cards allowing you to compare and make choices between, for example, creating a new space programme, funding further fusion research, or rebuilding cities.

Behind the scenes we have a detailed model that tracks everything from population demographics, to GDP, Human Development Index, energy use and emissions. The model took 14 months for us to get right. The value of it is like having a good suspension model in a racing game: it's not in your face making you think about things that make your brain hurt, but it ensures the feel of the gameplay is right. The narrative stays coherent and responds appropriately to what you do.

Ian Roberts: The world is divided into regions (each with their own problems and contributions to the system) and you push the regions to do things you want. Sometimes the things you try will have major side effects, sometimes the regions will push back, sometimes the climate will throw hell at you and sometimes you totally deserved it.

It's all choices and in that respect it's pretty free-form. 'Do I need to build flood barriers? What if I just squeeze this region dry before that happens... oh their homes are all flooded and they're migrating to my richest region. Good thing I built a strong military to keep them out. I suppose :/'. Ultimately though there are objectives that the player chooses which have win conditions, lose conditions and ways to score the player depending on whether the results were part of the plan.

RPS: You talk about exploring some radical solutions. For those who aren't following cutting-edge climate research, care to talk about the sort of big actions you can try? And what can go wrong with them?

Gobion Rowlands: Before I answer that I should tell you what kind of player I am. I love the big technology solutions that feel sci-fi. So with that in mind it is probably not a surprise that I am interested in geo-engineering projects - space mirrors, giant titanium heat fins, arcologies, vertical city farms, transhumanism, colonising mars and fusion power. What surprised me is how over the last few years I have found as much passion for the smaller, personal, actions.

Ian Roberts: When it comes to climate change, you can avoid it, reverse it or sit and take it.

To reverse it you're going to have to do some serious meddling with geo-engineering and you better get it right. You could deflect the sun with reflectors or sulphur. Maybe it will work, maybe it won't but you better hope it does the right amount because going to far in the other direction could cause an ice age. You could try scrubbing the emissions back out. Remove them too quick and you have massive flooding on your hands from all the water vapour still in the air from

when it used to be much warmer.

Avoiding it is the obvious one but we're utterly reliant on fossil fuels for the world to function right now. If changing that reliance isn't your thing, you could always just engineer a way to kill off a few billion so we don't need so many coal plants and SUVs. Virus? War? Military state? Choose your poison.

If you're going to sit and take it, how do you prioritise? Do you move everyone away from ground zero? Do you defend against the floods, the fires and the droughts? Do you build a brave new world - underground, in one part of the world, on another planet? What happens to everyone who isn't part of it or isn't protected?

These are simplifications but those are the kinds of stories you can expect.

Klaude Thomas: To quote one of the reports we read, 'Geoengineering technologies can be divided into three broad areas: solar radiation management (SRM); carbon dioxide removal and sequestration; and weather modification.' Carbon dioxide removal sounds pretty good, right? We put the carbon into the atmosphere, let's scrub it out again! The trap for n00bs (basically, humanity) is that carbon dioxide has a limiting effect on precipitation, while warming of course increases the amount of water vapour in the air. Since temperature change lags carbon ppm (parts per million) change, the air will stay relatively highly water-logged for awhile after the carbon is scrubbed out. Suddenly removing that carbon allows precipitation (rain) to potentially spike way, way, way above normal, or even totally torrential, levels. Apres moi le deluge!

Another example would be the simple expedient of removing a large proportion of the planet's population from circulation. Let's say with an engineered super-virus. The first thing to say about this is the obvious, that killing every last person in Africa would have less impact on climate change than getting Westerners to use 10% less energy. But let's say you spread the virus around evenly, so everyone loses say half their family (the half who always get them crap stuff for Christmas). The trouble is, people don't just conveniently fall over and die. Their friends and loved ones have to go and try and keep them alive, or always want to bury them decently instead of just tossing them in a skip; and then they spend time moaning and weeping and what have you. And that guy in IT who was fixing your laptop? He's gone, and so, by the way, is the engineer who was keeping the power station running. So the rest of your society stops working so well, and that potentially puts your civilisation into a downward spiral as critical infrastructure falls apart.

Just like Survivors (the TV series by Terry Nation). Another of the most important big actions to consider is fusion power development. The trick here is to think about what happens if we don't do anything and just hit on fusion tomorrow. How long does it then take to get fusion tech into China and India (the big future emitters), and how long to replace own own power stations. A reasonable estimate for several reasons (partly to do with stock turnover in the energy sector) would be 20-50 years. If it's 20 years, we're fine. If it's 50 (or if we do not, in fact, have fusion tomorrow) then we'd be committed to enough warming to cause serious problems. Again, due to

lags in the climate system.

RPS: You've mentioned a couple of science-fiction reference points in some of the answers. What other, fictional pieces have you been drawing on for atmosphere or inspiration? I found myself reading Wyndam's polite apocalypse novels recently, and the vision of London sinking in The Kraken Awakes stuck with me. Anything like that on your mind?

Gobion Rowlands: My largest influences have been the tales and stories of the amazing people I have met in my career. Over the last couple of years I've been fortunate to become friends with Pen Hadow, and Arctic Explorer. His tales of savage winds, terrifying encounters with polar bears and arctic wolves, ice blindness and unavoidable extreme hallucinations when you are so far from help stimulate my imagination (and my awe of his crazy awesomeness). I have one secret trashy inspiration on the lines of a sunken London - the Rutger Hauer movie Split Second which is set in a flooded London. I saw it when I was 15 and it had a surprisingly large impact on my creative thinking about London.

Ian Roberts: When you get into the more apocalyptic scenarios, sci-fi is definitely the first thing that comes to mind but honestly we don't need to look much beyond the climate research to find shocking visions of the future. Where sci-fi really inspires is in the social aspect, the cultural consequences, the unfolding drama of how one possible crisis-struck world may react. "World War Z", for instance, with its extreme isolationist themes is one especially horrifying and disconcerting reaction to a world swarmed by those dispossessed by disaster.

Thematically, the game has mixes of golden age sci-fi, enlightenment literature, Randian socio-political nuttery and 80s enviro-enthusiasm. It's the players, though, that will bring out these themes in their choices - whether the future is all airships and metropoli or happy green pastures just outside the grim enslaving industrial states is up to them.

Klaude Thomas: I do think of Wyndham's 'Chysalids' of course. We'll also be offering players some of the more chilling choices as seen in films like Logan's Run (Carousel!) and Soylent Green. Scifi writers have been speculating about this kind of thing for decades, so as you expect they offer a lot of ideas for 'what iffing'.

RPS: And, finally, what are you doing between now and release? What challenges have to be overcome?

Gobion Rowlands: So my first task was to finish fundraising but I am very happy and relieved to say that is complete now, so my job now becomes touring Fate of the World around the world and showing it to as many people as possible. I made a decision earlier in the year that launching an indie game is like launching an indie band, so to really build long term success and a genuine connection with your fans and players you need to go on tour. Given the subject matter we cover and my own personal convictions as much of that as possible will be by train. It is somewhat awe-inspiring task but one I am looking forward to.

Ian Roberts: Getting in all the diverse narrative that the subject deserves. The outcomes in the game have to be broad - there are so many possible futures. Giving players enough choice to make dramatic course changes and having the world respond in interesting ways is the core of the game and the task ahead is making that as rich and satisfying as we can.

Klaude Thomas: Finishing the game, and making sure it is good.

Fate of the World will be released in August, with a Mac Version following 6-8 weeks later. You can follow its progress at Red Redemption's site, or Fate of the World facebook or twitter pages.