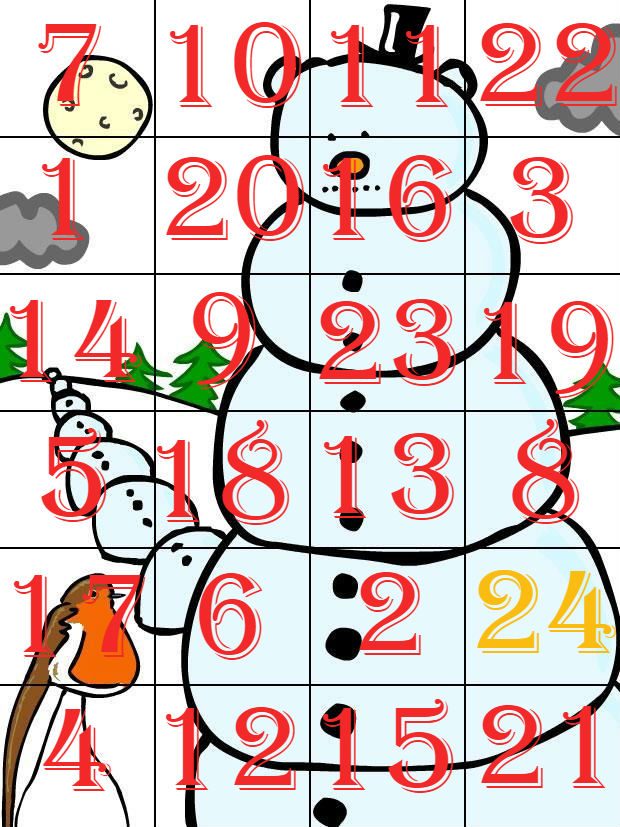

Our PC games of the year 2017

Calendar condensed

The calendar's doors have been opened and the games inside have been eaten. But fear not, latecomer - we've reconstructed the list in this single post for easy re-consumption. Click on to discover the best games of 2017.

To explain: RPS picks our 24 favourite games released each year and reveals those choices on the countdown to Christmas like a daily chocolate treat. Each chosen game is left a surprise until you click through to the post, which means those 24 posts are easily lost within the vast RPS archives. This article collects those 24 games together into a single post, so they're easier to find for future generations who want to know what what floated our boat in 2017.

You have two methods of navigating this post. One is to use the little arrows below the header image or the arrows on your keyboard. The second is to click the doors of the advent calendar below, which will zip you to the page with the game originally revealed on that day. The games aren't in any order, except for December 24th which is objectively the year's best game. Enjoy!

Wolfenstein II: The New Colossus

Alec: A first-person shooter with heart. And also with the sort of bug-eyed mania that means seeing even a single moment of the game out of context paints it as bellowing, hyper-violent incoherence that's trying to say and do far too much at once. Which is a totally fair cop, but the thing about Wolf II is that, if you're with it from the start, almost every splurge of splenetic nonsense makes sense, has connections to events and people and most of all to its star BJ's internal monologue, which itself is equal parts impossibly true grit and glum self-doubt. BJ grounds the mania, makes it all work when, in almost any other game, it simply would not.

BJ Blazkowicz, the original FPS lunkhead, now the vanishingly rare heart and soul of the 21st century action game - whoulda thunk it?

Given the insane discounting of Wolf 2 not long after launch, my guess is it's not sold too well, and we know what not selling too well means both for franchises and experiments. If Wolf 2 ends up being a full stop on a certain style of single player action games, it is, at least, a very fine and heartfelt one.

Adam: The New Order, MachineGames' first trip to Wolfentown, is a better shooter than the sequel. I replayed it right before I dug into The New Colossus and two things stuck out - it's massive, and it's amazing at sneaking, stabbing and shooting. The first time I played, I was so astonished that it not only had a story but that it had characters that I cared about that I don't think I noticed quite how good it was at everything else.

Wolfenstein 2 is a damn fine shooter as well, but sometimes I found myself waiting for the action to finish so I could get back to the story. The fact that I can write that sentence, sincerely, about a Wolfenstein game still seems weird. It probably always will. But that's fine because Wolfenstein is a weird game. It's silly, frightening, romantic, hilarious, exhilarating, wonderful and ugly. As Alec says, Blazkowicz is at the heart of it again, wounded and weary, a man burdened by his own myth. He's a hero, but he's sometimes a reluctant protagonist, preferring to listen and follow than to lead.

Thankfully, he has a supporting cast more than ready and able to lead. They're the real stars here, showing the cruelty and nobility and anger and hatred and fear that are so often missing in depictions of war. Nobility gets flushed down the toilet, brothers in arms are jostled aside to make place for their sisters, and there's a manic glee alongside the terror and pain.

I think it'll find its place in history as one of the great singleplayer first-person shooters, and I'm fairly sure it'll be the game I always think of when I cast my mind back to the things I played in 2017. That's because it didn't just capture the zeitgeist, it performed an act of extraordinary rendition on the zeitgeist, spirited it away to parts unknown, and ripped its shrieking soul out so that it could plaster it, garish and loud, onto a screen. Whether you think the game (and its marketing) performed a crude hijacking of political concerns or delivered a cathartic and triumphant smackdown (or blew a gigantic raspberry), I'd love to hear what you think.

For me, Wolfenstein 2 worked. As a story, as a (anti-)rebel yell and as a beautifully crafted game that goes to some very ugly places. I look forward to going wherever MachineGames take me next.

The Norwood Suite

Adam: The Norwood Suite is a game about visiting, and working in, the best hotel in the world. The Norwood isn't a great hotel because it has particularly comfortable beds or a great bar, it's great because it's a concert hall and an art gallery and a place for a bunch of interesting people to hang out and discuss music theory.

"Oh no," you might be thinking. "I don't want to discuss music theory or to listen to other people discussing music theory. That sounds like it'd either go over my head, under my radar or just bore me to death."

The reason The Norwood Suite is so great is that it delivers all of its cleverness without showing off or condescending. It's like having a conversation with a very smart and generous person, who leaves you wanting to know more about a hundred different topics, but always feels like a storyteller rather than a professor. It's a game I'm comfortable to wander around and to study, to enjoy and to analyse.

There have been many musical games, from Gitaroo Man to Amplitude and Epic Mickey 2, but The Norwood Suite is the most thoughtful and joyous one I've encountered. It's faintly sinister too, which is great if you like that sort of thing (I absolutely do).

Alice: Despite the giant stone heads, the slicing machine with feet and the head of a dachshund, the musical bowling pins dominating a hall, the eyeball in the Wi-Fi router, the book of spiders, the grasping hands around a doorway, the impossible sheet music, the secret diorama tunnels burrowing through the building, the murals of man and beast, the bedroom containing a miniature city bopping to a beat, the giant mushrooms, and the piano in the oven, the Hotel Norwood is not a strange place. It just is. I adore the bricolage style throwing together so many disparate objects, styles, and motifs so intensely that the hotel is just itself - often surprising but never kooky.

It's a great place to visit but, as Adam says, the way the building intertwines with the stories of everyone drawn to it is extra-great. It's a catalyst for a life-changing visits. I still find parts of the hotel -- and especially of some guests' stories -- popping back into my mind.

Torment: Tides of Numenera

Matt: It’s possible that one of my most memorable gaming moments was a product of chance more than design, but Tides of Numenera is smart enough that I can justify believing that isn’t the case.

I was in my first dozen hours of the game, and my party contained the maximum of four characters. One of those was a little girl who I’d found huddled in a ruined house, trying to sequester herself away from a bunch of thugs. I saved Rhin and took her in, despite her being a liability in every confrontation I got into. At one point I decided enough was enough, that she’d be safer if I sent her away - but her reaction when I told her it was time for her to leave made me reconsider.

A few hours after that, I got the chance to recruit a deadly assassin into my group. It was an opportunity I couldn’t pass up, so I gritted my teeth and told the girl she had to go. Rhin ran off, crying - directly down a passageway marked by hundreds of handprints. When I examined them, I learnt that they were the last marks of hundreds of souls who’d come to that spot to end their lives. I followed the tunnel to its end, where I was horrified to see it open up into a sheer drop from a cliff face.

I went straight back to the ruins where I’d originally found her, and was relieved to find her back amongst the rubble. It was near the start of the year when I played Tides of Numenera, but I vividly remember the ninth world as a setting, where millions of years of history and technology from ancient societies create space for anything imaginable to happen. I remember the game’s philosophical exploration of concepts from justice and the self through to the metaphysical. I remember the decisions I was forced to make, which sometimes made me question my assumptions about right and wrong.

But most of all, I remember that moment with Rhin.

Bayonetta

Katharine: PlatinumGames may have made its name on console, but golly, what a treat it is to finally have Bayonetta on PC – and the best version of it as well. Whatever your feelings are about the titular witch herself, this outrageously camp action brawler is an absolute delight. Its combat is second to none, and slipping past enemies in slow motion before laying gigatons worth of damage on them is just immensely satisfying. There's also nothing quite like its larger-than- life boss fights and (literally) hair-raising finishers. It's so ridiculous, in fact, that it's just got to be played to be believed.

If you haven't kicked an angel in the face with a six-foot- high stiletto heel, ripped off a god's arm with a fist made from your own hair, or motorbiked your way up the side of a rocket while fighting off hordes of seraphim with nothing but a pair of guns, you simply haven't lived.

Adam: I love Bayonetta. Creator Hideki Kamiya was also responsible for the original Devil May Cry, a game that made me feel like I wasn't cut out for this kind of super-stylish action hack 'n' slashing. It was tough and I never felt like I was doing anything more than stumbling around and embarrassing myself. When I watched other people play, they made Dante look like a super-agile monster-slayer. When I played, he was like a drunk with his shoelaces tied together.

Bayonetta, by design both visual and mechanical, makes me feel like the best witch ever and that is a wonderful thing to be.

Graham: Adam hits on something important. I think people assume that Platinum action-combat games are about beat-'em-up-levels of button dexterity. They can be, if you want them to be, but they scale so well to even people with fat, brittle fingers like mine. Bayonetta includes an "automatic" mode in easier difficulty levels that handles positioning and allows you to perform an array of attacks by pressing only a single button. If you just want to experience the games absurd spectacle, then you can do so and be entertained without being challenged.

If you feel ready for more, you can turn off the automatic mode and continue to play on Easy or Very Easy difficulties, and it's a great on-ramp to getting better at the game's combat. These modes make enemy attacks slower, making it easier for you to time your blocks and dodges, and on Very Easy your health will regenerate over time. They create a space for you to experiment and, little by little, you'll learn how to not just beat enemies but to do so with greater degrees of flair.

I think it's worth taking that journey of self-improvement, but ultimately, Bayonetta is worth playing even if you're bad at it and planning on staying that way.

OneShot

John: Released in December last year, OneShot employs RPS's unique Advent Rules for inclusion in this year's list, and goodness me, it deserves it. OneShot is unlike anything else you've played, which is quite the claim to make in such a saturated gaming world. But a true claim.

(And no, don't let anyone tell you, "it's a bit like Undertale". If you bounced off Undertale as hard as I did, ignore this. OneShot is doing something very different, something very specific.)

First, and most importantly, you are a character in OneShot. The main protagonist is a lost little girl, known in the strange land in which she finds herself as "the Messiah", clutching a light bulb the locals think is the sun, and bemused as to how she got here. But she's not the game's only protagonist - that's where you come in. And indeed the game itself. The game is a character in this game.

The layers start piling up, and then peeling off, in ways I've never seen a game do before. The first time it popped itself out of fullscreen to a little RPGMaker window, and then a dialogue window appeared on my desktop directly addressing me (presumably using my Windows account to get my name), I was utterly spellbound. And that's its move for the opening moments - it gets smarter and more interesting the further you get.

But what makes OneShot so very, very special is that it's not a collection of super-smart gimmicks - it's a wonderfully compelling and moving story that embellishes itself with all these fascinating, frame-breaking ideas. Where it could have been smug, it's instead full of heart. I cared about Messiah more than any gaming character I can think of in years, her vulnerability made so much more meaningful by her directly engaging with me as she explored. She knows I'm there, the game knows I'm there, and she knows the game's talking to me instead of her. And none of us is entirely comfortable with the situation.

This becomes more complicated by Messiah's understandable assumption that you, the person playing, might be some sort of god. The game lets you choose whether this is something you want to lean into, or dispel her of immediately, and knowing which way to go isn't simple.

And then it just keeps getting cleverer. It does things I didn't know my PC could even do. It messes about with you desktop, it uses hidden files, it... well I can't spoil the good stuff. I can just implore you to switch off any non-standard desktop management software you might have running before you start (I had to disable DisplayFusion). And none of it is for the sake of it - all these odd little features directly tap into the story, and deepen the relationship between you and the game, and Messiah herself.

Oh, and even the game's name is a stunningly clever little idea, that reveals itself as you play. Oh gosh, it's all so clever, but also all so lovely! Games this special are rare, and it'd be such a shame if you missed out on OneShot because of its RPGMaker wrapping. It's gorgeous and smart and packed with feels, and the most innovative game in forever.

Northgard

Matt: I haven’t played an RTS since Starcraft, so Northgard was a great reminder that not every game in the genre has to be about constant micro and maximising your actions-per-second. Northgard is a much more sedate game, where you can’t even attack your opponents until you’ve sent a scout to map out their territory.

You have enough to worry about without antagonising the other factions, anyway. Wolves and Draugr present a constant threat if you don’t commit to wiping them out, but focusing too much on your military can result in your people starving and freezing when winter comes. On top of the harsh food and firewood penalties, every winter also brings a calamity like an earthquake or a rat plague, which will wipe out your food stores and spread sickness amongst your clan. They’re a nightmare to deal with, but boot up the multiplayer and It’s all worth it to hear the panicked screams of your friends.

Brendan: God, I love competence. Northgard is a viking strategy that simply knows what it is doing. It is competent. If that sounds like faint praise, it shouldn’t. This land-grabber is merciful to dabblers and those new to the RTS, while also being faithful to the genre that Company of Heroes so excellently reformed. You nab bits of a randomly-generated island, each plot having its own benefits. Maybe there’s some fertile land there to grow a farm. Maybe it has a stone circle you want to examine. Maybe you just need it for longhouse real estate.

Whatever the case, you expand to expand. But conquering isn’t a simple matter of rolling over everything with troops. Victory can be achieved through military might, but because of the low population cap each warrior lost to the axe feels like a harsh blow. And since you’re often re-assigning villager’s tasks, each fighter is also a potential hunter, merchant, or witch doctor. That makes it tempting to go for other types of victory conditions. A good trading plan or lore-farming strategy can also win you the game. Although there will still be challenges. Harsh winters can leave you without food. Giants can ally with your foes and come stomping into your territory. An armoured bear can eat all your fishermen. Like all good map-based strategy games, Northgard is about staying in control when everything is going wrong.

Songbringer

John: Procedural generation is so very often used to great effect in games where starting over is a frequent occurrence. As a result, the gaps, the less impressive joins, tend to be more dismissible, because hey, a new one will be along in a minute. So when a linear game is bold enough to let its entirety be procgen, that's something impressive. That's the first time Songbringer is impressive.

Once you've seeded your world, with a string of six letters or numbers, it crafts a unique version of its collection of enemy-filled individual screens, expansive underground dungeons, and hidden items, upgrades, and NPCs. And then weather, ground conditions, shop contents, monster density... And that's your game world, from start to finish. A decent chunk of time, as you follow the daft story through.

The story is of crashing on a planet surface, and attempting to recover, and prevent a big bad. It's nothing original, but nor does it set out to be. It's breezy, a background, but with enough fun dialogue and silly moments to not feel in the way. And indeed, that your original ship's navigators were called Rosenbow and Gildenstern is reason enough for the game to exist.

What you do is explore, discover, and be constantly overwhelmed by how utterly beautiful are its pixel graphics. Think Sword & Sorcery, lit by God. The lighting is so ludicrously wonderfully throughout. From that point on, it's a very deliberate tribute to early Zelda, without ever actually feeling like a Zelda clone.

A screen might have one or two enemy types, each requiring different tactics to fight, allowing you to build up quite the mental bestiary. Dungeons contain multiple rooms, keys, and bosses. You gather new skills and equipment throughout. It's very Zelda in some respects. But it doesn't attempt the same twee atmosphere, the same noble themes, and most importantly, none of Zelda's various styles. That, and the procedural generation.

And it all works so splendidly. It's witty, breezy, and absorbing. There's always plenty to be doing, it's always a huge pleasure to look at, and yet it feels comfortably relaxed, the sort of game to play while enjoying a podcast - comfort gaming. It's been one of my stand-out games of the year, and yes, I've seen the middling reviews it's received elsewhere - I can only assume they were expecting it to be something else. Just enjoying it for what it is has made it one of my favourite things in 2017.

Adam: I haven't spent enough time with Songbringer and I'm hoping to remedy that over the holidays. The first time I played it, I was at Devolver's lot at E3. Rather than being hidden inside the sweaty halls of the convention centre, they occupy a carpark, bringing their brand of outsider anarchy to a little patch of escapism just outside and opposite the showfloor. I always enjoy visiting because there are plenty of developers to talk to and no crushing queues to endure.

Nathanael Weiss, the developer of Songbringer was there. I think he was wearing a pointy wizard hat. We spoke for fifteen minutes or so and he told me about his background in game design, how he had dropped out of the industry for some time to travel. It sounded like he'd gone pretty far off the beaten path and some of the experiences he had made it into Songbringer. It doesn't look or play like a travelogue, but I think Weiss' journeys were an important part of his approach. Images and ideas have leaked in, and even though Songbringer is fantastical and strange, it feels like it's driven by dreams and figments of memory and imagination rather than world-building and homage.

As John rightly says, it's very Zelda in some respects. Early Zelda, with the single screens connected into a larger world. But it has a beauty all its own, with some of the best pixel graphics I've seen in a long time, and most importantly it feels like the work of a singular mind rather than a deliberate attempt to (re)create a link to the past. Zelda is a reference point but so are hallucinogenic cacti. I think they're both equally important.

Hand of Fate 2

Alec: A delightful melting point of recent gaming vogues: CCG, dodge-or-die combat RPG and survival/permadeath roguelike. HOF2 does a hell of a lot in a remarkably understated way - it could well have wound up wearing an ill-fitting costume with garishly clashing colours (the Sixth Doctor, if you will), but instead it pulls it all off with cool aplomb. The plate-spinning always feels thoughtful rather than frantic, and a structure that essentially sees the game composed of lunchtime-friendly short stories suits it down to the ground.

The broader focus over its predecessor means that game's best feature, a wryly malicious narrator/rival, is sadly lost in the mix. As such, I don't feel locked in battle with my own computer in quite the same way. But maybe the same joke wouldn't have been funny the second time anyway.

Adam: I liked the first Hand of Fate well enough but I'm surprised by how much the second has won me over. It's doing something similar to games like Guild of Dungeoneering, HeroQuest and Pathfinder Adventures by offering bite-sized quests with a boardgame-like structure. But in a year that has seen bitter (and often justified) complaints about unlockables in the form of lootboxes and the like, Hand of Fate 2 is also a brilliant example of progression done right.

New cards and adventures are unlocked through skill and experimentation, and everything about the system of unlocks and discoveries is designed to encourage thoughtful, playful interaction.

Getting Over It With Bennett Foddy

Graham: You are a half-naked man in a cauldron of water. A mountain stands before you, made of rock and metal and detritus. You can only move by using the sledgehammer in your hands to lift, shove and swing yourself across the terrain. Just the concept alone makes me fall in love with Getting Over It.

That concept is taken from another game, called Sexy Hiking, released for free in 2007. What Getting Over It does is pair it with nicer art and physics, which is fine, and with narration by creator Bennett Foddy. It's the narration that takes it from diverting novelty to sublime physical comedy. Foddy explains the philosophy of the game, drolly remarks upon your setbacks and comforts and mocks in equal measure. You can best get a sense of it and the game via the trailer, which is the best of trailers.

Foddy is best known for QWOP, a game I enjoyed a great deal, but controlling your sprinter's limbs made progress feel impossible. It resisted serious attempts at success. Getting Over It by comparison always seems achievable. You can move your character forward in easy arcs just by rotating the hammer against the ground. You can punt yourself into the air by flicking the axe against the ground. You can, quite quickly, make what feels like substantial progress up the mountain.

This is, of course, a trap. You will hit a hard part and you will make a mistake and this mistake will send you all the way back to the beginning again. In QWOP I would just give up, bored or frustrated. I'm never frustrated when I fail in Getting Over It. Instead I think: I can do it again, and I can do it better. Suddenly it's hours later and there's a pain in my neck because I've been tensing my entire body with each tricky maneuver. As the trailer says, Getting Over It was made for a certain kind of person. I am that kind of person - and it hurts me.

Alice: One single motion explored to its brutal extreme. It is delightful - and I really mean that. Between the bricolage of everyday objects making up the level, Foddy's narration, and the gentle building of tricks, it smiles as it stamps on your fingers while you dangle above a precipice. Don't get angry, get over it.

Rakuen

John: I honestly wasn't sure which way it was going to go. A first-time developer, even if that developer was Laura Shigihara, she behind many great gaming songs and soundtracks. An RPG Maker game in a gaming world drowning in RPG Maker games, despite stunning names like OneShot. And a game that, despite not having any meaningful overlap, felt like it was being released in the shadow of Kan Gao's To The Moon.

But Rakuen was better than anything I was hoping for. A wonderfully beautiful and emotional tale of a young boy (mostly known as "Boy") and his mother, who escapes the fear and sadness of his extended hospital stay by escaping into a magical world. A game exploring life and death, fear and love, and in a way that no other game has ever come close to, the relationship between a child and his mother.

It's also about an awful lot of things that it doesn't make clear for a good long while - things I therefore won't reveal either. But weighty subjects that you'd not be expecting, approached in gentle, intelligent ways. The game is metaphor laid upon metaphor, its central conceit of switching between a hospital and a magical fantasy land much more complicated than that fairly standard fare suggests. It's not nearly so simple as one being real, the other imaginary.

As you journey, you solve puzzles and perform deeds in both realities to explore the lives of the other patients on your character's floor of the hospital. If anything, it's here that the game slightly overlaps with To The Moon, where it's mature enough to understand that people's lives are messy and complex. That someone isn't grumpy because of a sad thing in their past, or whatever else your standard game plot might use as a pretense at depth. There's more to it, people are multifaceted. And throughout, through every moment, is the fear, the question, the nagging, niggling, incessant worry in your mind, that you just don't know why the boy you're playing is in hospital, and you just can't bear to think about it too much, not now, not for this bit, maybe later.

It's the relationship with Boy's mother, Mom, where the game is at its very best. It's a portrayal of real, unhyperbolic maternal love that feels so honest and raw and huge and ordinary. And it's not incidental, either. Mom accompanies Boy for most of the adventure, there to provide colour commentary, and sometimes hints, but most of all, to - you know - be this little boy's mummy. A dynamic relationship at the heart of a game is so ludicrously rare, and Rakuen is a template for everyone else to follow.

This is a game that features no combat, but packs so many punches. Will you cry? Bloody hell, yes, you will cry. Through tears I found myself, out loud, begging the screen not to let the plot go in one particular direction. In fact, my only criticism was that it perhaps pushes toward sadness a little too often. I was emotionally exhausted by the end, and I think a little more light could have shone in some places. But saying that, it's often very funny too, and there are some absolutely hilarious characters. When I reviewed it, I made the obscurest of references, comparing its humour to that of Dragon Quest Heroes: Rocket Slime. I repeat it now.

And because it's a Shigihara game, of course there are songs. Lovely songs, and even lovelier background compositions. The whole thing is something exceptional, and unlike anything else you played in 2017. There are so many layers, so much more going on than you might guess, and characters you'll feel like you actually know by the end. It's completely marvellous, and you'll thank me once you've played it.

West of Loathing

Alec: Ah, I'm so glad this made it onto the calendar. Almost no other bugger on staff played it, to my knowledge, and maybe that's because they're all cruel and heartless fools, or maybe it's because its simple stick figures and mugging to camera makes it seem too throwaway. Maybe it is. Maybe A Guaranteed Nice Time is just not enough in this age of constant shiny new or delectably experimental things.

But! Everyone should play West Of Loathing, because A Guaranteed Nice Time is also a very rare thing in this age of constant shiny new things all thumping their chests and selling us lootboxes and telling us ponderous, cutscene-heavy stories about how war is bad but now go shoot everyone. West Of Loathing, a halfway house between point and click adventure and low-maintenance RPG, is so warm-hearted that I want to hug it forever, even though one thing it never, ever is is even faintly mawkish. Its tone, its constant humour, its message is Have A Good Time. It is a game, and a very silly world of cowboys and magic, in which almost everyone is enjoying themselves. Even when they're shooting each other.

The temptation to make trite observations about the dark world of 2017 is very strong here, so I shall sidestep that particular issue by saying: a game as straightforwardly joyful and funny and companionable as WoL is such a valuable thing right now. Hell, even the very medium of videogames is often a hideous battleground; WoL reminds me that games, at the end of it all, are about having a jolly good time. It is full of characters and throwaway gags and callbacks and silly walks and crazy items and tiny hidden features that are all, each and every one of them, designed to coax a smile from our weary faces. And: those simple stick figures and their silly walks have a thousand times more personality than even the most impeccably-rendered photoreal megabucks game character, I assure you.

I don't think there's even a single Christmas reference in West of Loathing, but nonetheless, it is by far the most Christmassy game on this list.

Adam: I played it, Alec! If crackers contained jokes even half as good as the worst gag in West of Loathing, they'd be very precious things indeed. It's not just a game with occasional jokes, it's a game constructed entirely using jokes as a raw material. The atoms that make up its very being are jokes.

What's really striking is that I don't remember anything cruel. Some comedy punches up, some comedy punches down. West of Loathing just tips its hat at everyone and invites them to a party.

Graham: I played it, too! Though admittedly only after you'd written this, Alec. I'm only a half hour in which means I'm only equipped to say that it is fun even in the first half hour, a claim so few games can make. I think I was wholly sold on it the moment it let me stick my hand elbow-deep into a spit bucket just to see what was inside.

Battlerite

Matt: The creative director at Stunlock Studios described Battlerite to me as ‘the fighting game of the Moba world’, and I can’t think of a better way of putting it. It’s the perfect antidote to the hour long slogs that Dota matches all too often become, offering ten minutes of top-down brawling where reaction speeds, accuracy and psychology are paramount.

As accurate as I think that description is, you know what? Just don't think about the word Moba. That word is loaded with too many connotations at this point, and while a round of Battlerite plays a lot like a teamfight in Dota or League of Legends, there are key differences. Yes, you'll still need to learn the moves of dozens of different characters, but that's nothing compared to the 100+ characters boasted by most Mobas. There are no items or levels to worry about either, which places every player on a level footing from the start of a match to its end.

That means success of failure is distilled into individual moments, rather than as a consequence of decisions you made 30 minutes previously. There's no room for playing passively in Battlerite: each second that you spend in that arena is one where two to three nearby enemies will be trying to kill you.

You don't need to worry about being pigeonholed into a particular role. There are tanks and support characters, sure, but every character has some way of dodging or countering their opponent's moves. Of course it's not as deep as Dota, which is a strength rather than a weakness, but because every single ability needs to be aimed there's a certain sense in which the skill ceiling is even higher.

Testament to that is the way it’s almost as much fun to watch as it is to play. Some of my favourite moments have been when me and someone on the other team were both spectating from the grave, watching the two remaining combatants dance around dodging and countering each other’s abilities. That said, nothing can compete with the rush I get when I’m locked in my own 1v1, and manage to win the round by baiting out my foe’s dodge move then punting them away into the encroaching death zone. Get in the bin, Thorn.

Night in the Woods

John: I'm very excited to see what's coming in this month's Director's Cut of Night In The Woods. It's because I'm wondering if one of my favourite games of 2017 might be getting a better ending.

Endings aren't nearly as important as it's often argued. I adored Night In The Woods in many ways. It is, one one level, one of the most extraordinary pieces of gaming writing I can remember, set in a vividly beautiful 2D world, exploring a mindset utterly different from any of my own experiences. I was transported into this disaffected space of directionless ennui and depression, unlike any of my own muddle of mental illness. I really cannot think of another game that has so effectively and affectingly had me experience someone else's life. Although this experience isn't without qualification.

The silly ending has no impact on any of that, really. It does rather rewrite a lot of what I thought was happening, and none of it for the better, but it doesn't take away from any of the incredible moments along the way. The terrible fight my cat-like character Mae has with her mum, and the crazed need I felt to patch things up with her following, sticks with me months later. And the incidental, the overheard conversations, the snippets of other characters' lives, that I pieced together into meaningful narratives as I walked by. And so, so many other things.

It took me a long while to find my way in. I struggled to like the game's voice for the longest time. And then, the more I lived it, the more I understood it. I resented Mae's perspective, I wanted to shake her, tell her to recognise just how much she has, to snap out of her behaviour. All horrible, terrible responses. The more time I spent with her, the more I understood her, if not empathised with her.

And I struggled with the lack of involvement for too long. For many hours, your main role is to press "next". As I said in my review, "I would absolutely watch this TV show, but I really resent being asked to crank a handle to do so." This begins to change.

But it all pales when I remember. When I think back to moments, conversations, late-night emotionally exhausted outbursts, and mall break-ins. I adore it as I recall it. I think that's what matters most.

Alice: Unlike John 'The Dad' Walker, I empathise with Mae too much. Oh god, all too much. So I like all the colours and antics and adventures and crimes and friends as well as the oh so many regrets and so emotional gaps that are hard to look at, let alone cross. I'm definitely not onboard with that handle-cranking comment either; beyond the importance of exploring the town myself, even just getting around I was happy bouncing on cars and kicking through leaves.

What a wonderful tired town full of wonderful tired people.

SteamWorld Dig 2

Katharine: This is how you do a sequel. I was a bit cool on the first SteamWorld Dig, which saw your rust-bucket hero gradually explore a subterranean wonderland full of jewels, poisonous bogs and zombie-like hobos who'd clearly retreated underground in fear of their new robot overlords, but the way Image & Form's built on this for SteamWorld Dig 2 has quickly made it one of my favourite games of the year.

It follows the same basic premise – you mine a bit, earn some cash, upgrade your tools, mine a bit further – but adds so much more. After proving itself with the turn-based strategy genre in the equally excellent SteamWorld Heist, developer Image & Form finally gets to stretch its platforming chops here with inventive, dedicated puzzle caves that lie off the beaten track, giving the 2D exploits of other Metroidvanias a real run for their money. The treasures that lie at the end of those caves all feed back into its new cog system, too, which brings a welcome touch of the RPG to Dorothy's expansive toolkit, giving you the freedom to re-spec your heroine with new abilities each time you return to the surface.

There's also just something innately satisfying about picking your way through the dirt one block at a time, listening to the soothing tones of your pickaxe strike hard and fast against its easy-going soundtrack. It's the perfect game for a lazy Sunday afternoon, and you'll miss it when it's all over.

Brendan: You know when you see a dog with its tongue lolling out, and you think: “Oh what a good boy!” Well, Steamworld Dig 2 is a good game, said in that exact voice. It’s friendly, warm and generous. If it were a big cuddly Labrador, it would only ever want to have fun with you. It’s old-fashioned, in that it’s also a Metroidvania, but here this is a strength, not a cliché. You’re robot miner looking for your uncle, and you’ve got to dig, climb and bash your way to new abilities. A hookshot lets you traverse that windy desert you couldn’t face before, a jetpack lets you smash through a soft, mouldy roof to a hidden cavern, a pressurised water bomb uncovers one of the many subterranean secrets.

In many ways, this is a videogame for traditionalists, yet there is something comforting in how well it’s executed. The platforming feels good, the characters are simple but likeable, and there isn’t a hint of grind. I can’t think of a better PC game for kids this year, but I’d also recommend it as a tonic for any adult who is weary of microtransactions, season passes, and the punishable-by-death business phrase “games as a service”. Steamworld Dig 2 is a reminder that games can be approachable, decent and un-selfish, even when they’re about hoarding gem stones.

John: Like Katharine and Brendan have both said, it's just so unrelentingly lovely. It is, in a year that has seen difficult games shine, a demonstration of just how much fun it's possible to have without difficulty, too. It's about constant satisfying progress in a gorgeous cartoon world, packed with daft NPCs, constant upgrades, and the joyous sense of success that the best metroidvanias deliver.

It reminds me of childhood games on the Atari, the odd one or two that were designed to be enjoyed and finished. But far more sophisticated, with its pleasingly malleable upgrades, and scale. And it has a hookshot. All the best games have a hookshot.

Zero Escape: The Nonary Games

Katharine: Arguably the greatest visual novels of all time (sorry, Danganronpa fans), Zero Escape: The Nonary Games is actually two games in one, bringing the excellent 999: 9 Hours, 9 Persons, 9 Doors and Virtue's Last Reward to PC for the first time. Instead of asking players to simply click through reams of (admittedly excellent) text, the strength of both games comes from their ingenious escape room puzzles and clever branching storylines that build in the idea of a traditional 'game over' scenario right into its overarching narrative.

To go into detail about each game's story would be stepping into huge spoiler territory, so let's just say this. In each game, you're one of nine people who have been kidnapped and placed in the mysterious Nonary Game - the first is aboard a strange replica of the Titanic, while the second appears to be in some kind of underground research facility. Each contestant also has a wrist watch that can instantly kill them if they disobey the rules, and the only way to get out alive is for everyone to work together in order to solve the myriad puzzle rooms that await. The only problem is that one of you is also the Nonary Game's main architect Zero, causing tensions to run high as everyone tries to figure out who in the group put them here and why.

The escape rooms come thick and fast, providing a serious work-out for your brain as you delve deeper into each one's deadly game of trust and betrayal, and the way the game forces you to work together with certain characters ensures you build up a rounded picture of everyone's motivations and suspicions. The characters are all beautifully realised thanks in no small part to some surprisingly decent voice-acting, and there are twists galore that keep you guessing right to the end. Yes, it might look a bit ropey by today's standards (these were originally DS and 3DS games, after all), but what's a few low-res textures when the rest of it is such a rich, succulent treat?

XCOM 2: War of the Chosen

Alec: Long-time RPS readers will probably have presumed this pick was a foregone conclusion for me, but, in all honesty, prior to WOTC, XCOM and I were on a break. Though I sank dozens of hours into it at release, XCOM 2 hadn't achieved the same compulsive lure upon my thoughts that XCOM 1 and its expansion had. It wasn't a well I wanted to go back to, due to a combination of my growing bad feeling about the irritating and illogical campaign map and DLC that made the whole show fussier and visually noisier. It felt like a game adrift.

Initially, War of the Chosen seemed to worsen that. Even more interruption and schlepp on the campaign map, even more wild costume options that fall a million miles from the stark white future XCOM 2 originally suggested, even more superheroic skills that fall a million miles from the X-COM/XCOM way of chance-based shooting. A frenzy.

Then, the cloud of chaos coalesced into a new sanity. A revised XCOM 2 in which not doggedly following particular paths, particularly on the campaign map, did not mean doom. An XCOM 2 in which every campaign meant a few roads not taken, real reasons to come back and do it all again, and an an XCOM 2 in which my mind-map of skill combinations and strategies grew and grew and grew. It felt like a pay-off for the thousands of hours I put into XCOM games, a real opportunity to take it to a new level, to be presented with all these possibilities and figure out new ways to use them. It meant incredible, impossible turns like this. It meant soldiers who felt really like rare and precious individuals, in terms of skills at least, rather than walking meat-pillars of ability points. It meant an XCOM that gnawed at my thoughts again.

Jeez though, the costume design needs to be ripped up and started again by this point. Mods to the rescue, at least.

Adam: XCOM 2 was already one of my favourite games of recent years and War of the Chosen is such an enormous and brilliantly designed expansion that it feels like a whole new game. It feels like Jake Solomon and his crew at Firaxis have finally made XCOM absolutely their own, by emphasising the unique abilities of individual soldiers and finally figuring out how to make the Geoscape busy with meaningful choices. At this point, XCOM is almost completely divorced from the original games in style, both aesthetic and systemic, and there are few games more likely to steal an entire weekend from me.

Matt: Alec said that ‘XCOM 3’ might describe XCOM 2: War of the Chosen better than DLC, and he’s not wrong. The expansion turns so much assumed XCOM wisdom on its head that it really does feel like brand new territory. XCOM’s always had a problem where the optimal way to play is to move your guys forward inch by inch, running each unit a minimal distance before placing them on overwatch.

XCOM: Enemy Unknown solved that problem with the Enemy Within DLC, which encouraged you to play more aggressively by placing juicy resource canisters deep into the map and limiting how many turns you had to reach them. XCOM 2 relied on turn-limits for a similar effect, but I like War of the Chosen’s solution best: make every soldier a superhero.

When my Ranger can cut through armour with a sword that never misses, my Sharpshooter can move and fire without any penalty and my Reaper can blow my enemies to smithereens before they even spot her, there’s no need to be overly cautious.

Tacoma

Brendan: An argument: Tacoma is better than Gone Home. The space station setting is more interesting than a middle-class house, the characters are better portrayed, and it gives the player more to do than nosy around, reading old notes. Part of this comes down to the way it rethinks audio diaries. You don’t just hit play and listen as you carry on rummaging through the bins. You get a holographic representation of the crew, pacing and walking and moving around the station. To listen in on one conversation, you have to follow whoever’s talking. To fill in the gaps and characters you missed, you have to rewind the holo-log, then follow someone else.

It’s neat and simple. And while I think the ending is entirely fluffed (although I can’t say why without spoilers) it remains one of the best space jaunts of the year and my favourite of the environmental story-telling gang so far, packed full of tiny details. By contrast, the rambling story of Firewatch and genre red herrings of Gone Home always felt to me like a lack of focus. With Tacoma, Fullbright have lasered in on what makes a good walkabout.

Katharine: I confess, I never much liked Gone Home, and I was expecting to feel largely the same way about Tacoma. How wrong I was. While its clinical, sci-fi setting might not be as immediately appealing or approachable as Gone Home's spooky old mansion, it's the subtler details tucked away inside its plentiful nooks and crannies that really make Tacoma worth celebrating.

Gone Home was a little too artfully arranged for my liking, but each of Tacoma's crew quarters feel thoroughly lived in – a welcome contrast to the stark corridors and functional work spaces you'll visit in between – and getting to watch these characters' personal lives slowly bleed into their public working personas is absolutely fascinating. To give an early example, you might discover that one of the missing crew mates has been reading (rather endearingly) a book on 'banter for the inspired social climber' in his personal AR desktop to help him settle in with this new group of strangers, and you can see the results of this play out in the reconstructed conversations you'll discover throughout the rest of the game. It's a brilliant meshing of the game's various exploration objectives, and it wasn't long before I found each crew member's individual story to be just as compelling as the central mystery. And that ending. Oh, that ending! Absolutely superb.

Prey

Alec: Probably my favourite game of the year? It feels like too safe a choice, too Mid-30s Gaming Man a choice, but what are you gonna do? I lost myself to Prey's world of locked doors and hacked turrets and silenced pistols and wide-open yet claustrophobic spaces in a way I did to little else in 2017. What can I say, it just ticked all my boxes, to the extent that I was absolutely determined to uncover and visit every last square inch of its doomed space station, and in turn recycle everything I found in it into upgrades and ammo, despite knowing full well that my lizard brain was in charge.

A slow burn game if ever there was one, moving on from my raised eyebrow at its over-zealous attempts to be a mystery without doing the heavy lifting of making me care first, and into something where the mystery scarcely seemed to matter. All that mattered was making this labyrinthine, inter-connected ghost ship mine. I can take or leave the plot, which has some nice ideas but overly dour execution, but really is just skin around the mighty bones of this latter-day System Shock. I'm delighted we found our way back to this degree of sprawl and slow pace after the glitz and excess of Bioshock Infinite. Both games, I suspect, are bookends to certain schools of 21st century gaming blockbuster. I have no idea what comes next, but I'm so glad that I got Prey and its myriad locked doors.

Adam: I thought the mimics were going to be the stars of the show, clever little enemies that make you wary of the environment, but it's actually the environment itself that marks Prey out as a monstrously ingenious game. It's a perfect space to play in, thanks to all those alternate routes and tricksy locked doors, but it doesn't feel overdesigned. I believe in it, as a place with purpose, and even though there's no doubt a heck of a lot of subtle signposting and hand-holding, I always felt like I was making my own way.

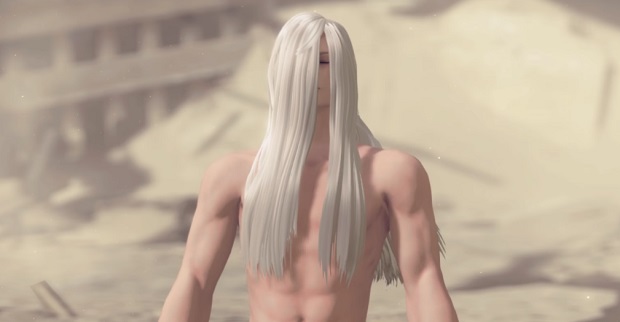

NieR: Automata

Katharine: What a ride Nier: Automata's had this past year. The sequel to a game about three people played on PS3 and Xbox 360 back in 2010, it just goes to show what a bit of PlatinumGames magic can do to an ailing cult classic. Okay, so the PC version of Nier: Automata was a bit borked at launch, but to dismiss it now would be a disservice to both you and action games as a whole.

For me, Bayonetta still edges ahead in terms of overall combat, but the way Nier: Automata effortlessly slips between about eight different genres – all in the course of a single level, no less – imbues it with its own kind of Umbran magic. One minute you're playing a bullet-hell shoot-em-up, the next you're in a 3D brawler, then a 2D platformer, and then to cap it all off you don a mech suit to an oil-platform-sized boss as an on-rails shooter. This is what video games are about, and that's just the first mission! Throw in an achingly beautiful world, soundtrack and story, and Nier: Automata is in no danger of being forgotten like its forebear.

Adam: I didn't have a horse in the NieR race. I've never played the original, I'm wary of sexybots and sad anime sci-fi, and I am not very good at many of the genres the game seemed to cover.

It turned out to be one of my favourite games of the year. For a good while it was my favourite and I still feel sad whenever I find out someone I know didn't get along with it. They have their reasons, and they're often good reasons. Automata does silly things, it winks at the fourth wall and then punches you in the gut, it veers between existential horror and weird whimsy, and I'm still not entirely sure why it's an open world game when I only really cared about following the story.

The thing is, it's so exquisitely idiosyncratic and carefully constructed that I wouldn't dare to second guess any element of it. Chances are, if you take away one of its uncomfortable qualities or moments, some of the best stuff in it might not work quite as well. It's a game of many endings; in fact, it's a game about endings in many ways. I wish it went on forever.

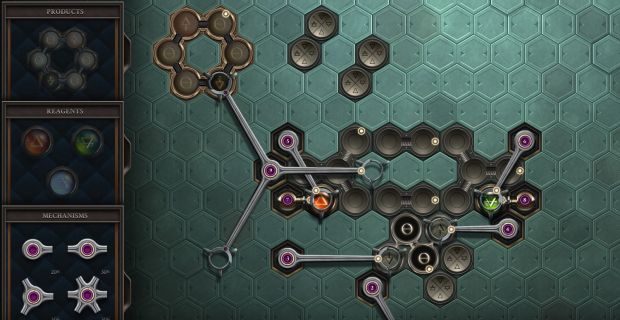

Opus Magnum

Brendan: Ah, the sweet ego-boosting hit of the Zachlike. There are plenty of puzzlers that make you feel clever for solving a fiddly problem. But this free-form alchemy engine is something special. You shift elemental marbles around with mechanical grabbers, bonding molecules together to create potions or hair gel or invisible thread. At one point, you are asked to create viagra (secret: it’s mostly salt).

Zachtronics games have a reputation for being difficult – the pastime of programmers and engineers. In many cases, that’s justly deserved. But here the machining is mostly straightforward. Later levels can take a lot of thought but there’s always a way to muddle through with trial and error, to hack together some brute of a contraption with more moving parts than should be necessary. In the end, you stand back from your wobbly, imperfect solution and think two things. First: This is very smart. Second: This could be smarter.

Matt: The best thing about Opus Magnum is that every solution is yours. Nobody else has combined pistons, tracks and calcifiers to make a stain-remover that’s gloriously wonky in the exact same way as mine. Other puzzle games might have multiple solutions that trick you into feeling like you're being creative, but at the end of the day you’re still following in the footsteps of a designer that’s laid those paths out for you. Opus Magnum gives you some tools, tells you what it wants you to make and leaves you to it. There’s no better way to feel like a genius, and unlike other Zachtronics that I’ve bounced off, this one’s accessible enough that I can get in on that too.

Graham: I've never got into any previous Zachlike, finding them fiddly or simply unappealing. I was convinced to try Opus Magnum because, after each solved puzzle, it has a menu button that lets you output a GIF of your solution. This is the most clever thing about the game. Its puzzles have aesthetic qualities beyond their success or failure as solutions, and the game recognises this by making them easily shareable. So when lots of my friends started playing the game, I started seeing lots of satisfying loops showing swinging arms and pumping tubes constructing unusual shapes. They were hypnotising. I had no idea what these clockwork contraptions were doing, but I didn't care: I wanted in.

To the game's credit, getting into it is as easy as those GIFs are pretty. The tutorial breaks down the concepts swiftly and the puzzles are framed by a story that's simple and sweeps you along. Even the game's options screen has some story dialogue to click through. I am not good at the game, but I could still muddle through most of its puzzles with inefficient designs, and when I decided to get better I did so by picking one of the earliest puzzles and playing it over and over again to improve my rating. I spent around six hours re-playing a single puzzle, entirely content.

Divinity: Original Sin 2

Adam: It's one of the best games I've ever played and there's only one RPG (Ultima VII) that comes close. Divinity: Original Sin 2 brings across and improves on everything I loved in its predecessor. There's the tactically exquisite turn-based combat, that involves manipulation of elements, freezing of blood, and as much slapstick as serious strategy. There's the reactive world, in which anyone can be killed, anything can be stolen, and quests can be completed by following the script or engineering systemic chaos. There's the weirdness of the world, which is as much Terry Pratchett and macabre mysteries as it is Dungeons and Dragons.

And then there's all the new stuff. Characters that I care about, plotlines that are sad, funny and strange, writing that brings everything to life in a way that all of the clever mechanics in the world never really could. Four player competitive play, in which you can deceive and betray your own party.

Divinity is drawing on the history of RPGs and it doesn't look quite as flashy as some AAA productions, but it makes everything else in the genre seem stuck in the past.

Matt: Both Divinity: Original Sin and its sequel excel at letting - even encouraging - the player to break the game, but it wasn’t until Divinity: Original Sin 2 that the devs really embraced that philosophy. Early on, you’re given some gloves that let you teleport any character or object at no cost beyond a few seconds cooldown.

I’ve used those gloves to sneak behind enemies, painstakingly getting each member of my party into just the right position before attacking. Sometimes I’ve used them to avoid combat altogether. There’s even a maze that requires you to painstakingly gather keys from other areas, unless you realise that you can bypass those gates by simply teleporting through them. There’s a talking gargoyle at the end that sneers at you for cheating, but with an undeniable sense of grudging admiration.

Playerunknown's Battlegrounds

Adam: I still haven't won a game. I still don't care. What a splendid thing this is. Even though it's a completely different proposition, it's effectively the game I wanted DayZ to be. Moments of tension, exhilaration, and laughter and curses shared generously over chat. I haven't loved a multiplayer shooter this much in years.

Matt: In one moment, Plunkbat is a calm, pleasant environment where I can enjoy a comfortable chat with my mates. In the next, it’s a ridiculously tense shooter where death can come at any moment.

I can totally see why Plunkbat might not be your bag. A typical round might consist of 10 or 20 minutes of peaceful looting, following by an unavoidable, unceremonious death to someone who just happened to get the jump on you. It speaks to just how exquisite the game can be that all those uneventful hours are worth enduring for those rare occasions when you can make it into the very last stage of the round.

It’s sounds like a silly exaggeration, but I’ve literally had times with Plunkbat where I’ve forgotten to breathe. The other day, I was in the final 5 as the circle closed to a miniscule radius. All of us must have been a few metres away from each other, laying prone in grass that provided just enough cover for each of us to go unseen. Then the circle shrunk again, and the air erupted with the sound of bullet fire and explosions as several people made a dash for it at once.

I didn’t win that game, but I have had my fair share of chicken dinners by now. Each one is almost as delicious as the first, where I jumped out of my seat and punched the air, most likely waking up my flatmates. Who needs exercise when I have Plunkbat to set my heart pounding?

Graham: As a kid, my friends and I would play a lot of hide and seek. Every so often our conversation would return to the same idea: wouldn't it be cool to play hide and seek over our entire town? It would never have worked for many obvious reasons, but that desire to map the drama, tension and empowerment of hiding and hunting onto large, urban terrain is so simple and obvious that it occurred to us as ten-year-olds.

It's those uneventful minutes that Matt describes which are my favourite parts of Plunkbat. If I want immediate action and instant gratification, the game can provide that: jump when everyone else jumps, race towards the ground, and you'll find yourself quickly in the midst of combat. But mostly what I want is to be hunkered down inside a bedroom on the second floor of a house, peeking out a window and trying to get a view of the gunfire I can hear getting closer. I want to watch another player walk by the house without ever knowing I was there, watching.

There's another game from my youth that Plunkbat resembles, and it's Counter-Strike. Not in the maps, which are obviously larger by miles, but in the emotional experience. The feeling of being the last person alive on your team, fighting against the odds, is rare in Counter-Strike but a permanent sensation in Plunkbat. The feeling of trying to escape unseen with hostages in tow is only happens after substantial success in Counter-Strike, but is present during every new building you infiltrate in Plunkbat. This is the game's triumph: it makes the highest highs of other games accessible to anyone, whether they're inexperienced or bad at first-person shooters.

Plunkbat plunkbat plunkbat.

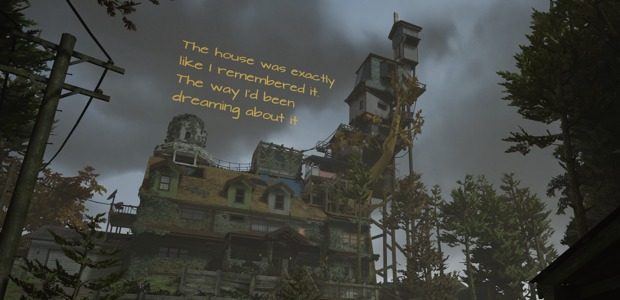

What Remains Of Edith Finch

Graham: You are returning home to a house from which you fled. You're in search of answers: what's the truth behind the family curse, which seemingly causes each member of your family to die, often young, in unfortunate, heart-wrenching and occasionally funny ways? You're the last Finch walking and you need to know. The answers will be found via the house's ornately modeled bedrooms, each of which prompts a vignette depicting the deceased's final moments.

The whole game is exquisite. The house is beautifully constructed, a masterclass of level design. It's simply wonderful to look at. There is only a single available path through its rooms, yet your discoveries feel your own. Every element is designed to communicate character. Storytelling by way of household objects and scribbled notes is not new, but What Remains' is built as carefully as a Rube Goldberg device. The clutter takes on meaning as you tumble through it.

Yet the vignettes take it beyond simply being Gone Homier. These are poetic and lyrical because the player is active within them, taking control of movement in a different way each time. Some are better than others, but all of them reflect and reshape the story you're gleaning from the environment.

The result is a game that deals with death with a lightness influenced by the works of Tim Burton, Wes Anderson, Bryan Fuller, but which has played on my mind every day in the month since I played it. In part that's because I'm still trying to work out exactly how much I like it. I suspect I admire it more than I love it. One of its stories reduced me to a bawling mess, but it was an easy target. Overall it shifts tones enough that I'm not entirely sure what, if anything, it was trying to say. I think its framing narrative is its weakest story, I didn't buy the ending, and ultimately I feel like it's not more than the sum of its parts... But when the parts hit the highs of What Remains?

Let's try this: What Remains is not my favourite story in videogames, but it is my favourite storytelling... And heck, it's one of my favourite stories, too. Damnit.

Let's try this instead: What Remains Of Edith Finch makes me excited for the future of the entire medium of videogames.

Brendan: There’s a scene in Edith’s familial myth-history that will resonate with lovers of videogames. It’ll spark thoughts for anyone who has sought escape from a menial job in this dumb non-reality we all adore for reasons none of us can remember, probably the flashing lights. I won’t spoil any more because this is a game that’s best enjoyed as fresh as a flapping fish.

Alec: All hail the short game - the game that does it all it sets out to do in just a couple of hours, then gets out of your way. Edith Finch goes the extra mile by packing in an almost obscene amount of environmental storytelling alongside its 150-odd minutes of wry tragedy and comedy, not to mention the wild abandon with which in introduces new ideas, control schemes and fever dreams every time it focuses on a new character. It's a game that lurks in the head for some time afterwards, and it's a game that is almost more satisfying on a second play, when you already know the tales of the wonderful, terrible, tragic, hilarious ways the various members of the Finch family died, and can now appreciate how all the little details predict and reference those stories.

And hell, the visual invention here, so much of which could sadly not be talked out for fear of spoiling the whole shebang, is off the charts. This is not some maudlin Gone Home knock-off: it's a feast of ideas, black humour and celebration of the power of stories.

Adam: I've written so much about it already, in our best PC games feature and in my review. Not as many words as I've written about games that I think are far less exciting or important, but enough to get my thoughts and feelings across. Graham says it makes him excited for the future of the entire medium of videogames and I'd agree with that. I'm more a systems and mechanics person than a narrative-lover when it comes to games, but Edith Finch made me a believer in this particular style of interactive narrative.

Perhaps I feel about it how everyone else felt about Gone Home, Firewatch, Dear Esther or The Stanley Parable. I like all of those games to varying degrees, but Edith Finch is the one that made me go, "OK, we've got this". And when I say 'we', I mean games as a medium, and when I say 'this', I mean everything.

Graham: I'm looping back in here after everyone else to point you towards some of our other reporting about Edith Finch from the past year. Specifically, if you've finished it, it's worth reading Alex's interview with the developers about the use of text in the game and Pip's interview with them about the art design of the section Brendan's referencing above. The latter also contains some great concept art and in-development images. As I've already said at length, the game is exquisite, and personally I found it fascinating to learn about how it was made after I was finished playing.

(Also we named it one of the best PC games ever.)

Dead Cells

Matt: I didn’t expect to spend 35 hours and counting in Dead Cells, but they snuck up on me. At the start, every new area (apart from maybe the first) is an awful, terrifying gauntlet that you have to slowly crawl your way through. Normal enemies seem relentless and tough, and the elite versions of them almost impossible to get past without chugging through an entire stock of health potions.

But over a few hours, with each repeated encounter feeling fresh thanks to the magic of procedural generation, that changes. You go from being afraid of the world to on top of it, sliding and slashing your way across platforms without pausing for breath.

Once I’m comfortable in an area I’m constantly in motion, dispatching an enemy every other second as I combat roll through screen after screen. The game plays to its strengths, rewarding you with a speed and damage boost for each enemy you kill in quick succession. Rewarding skill with power might be a questionable design choice in a multiplayer game, but here it adds to the feeling that you’re a slick, unstoppable ninja.

There’s more to praise than the movement. A smart unlock system means the currency you collect from every slain enemy feels genuinely meaningful. The upgrades dovetail with your growing skills to allow you to push deeper into the game, expanding your arsenal as you do. I get far more excited about finding a rare blueprint in Dead Cells than I do a new gun in Destiny. Plus, it’s got the most gorgeous pixel art since Duelyst. I’ve only spent an hour or so with the latest update, and who knows how much more time I’ll have put into it by the time it’s actually finished.

Alec: I was a Johnny come lately to Dead Cells, not able to fit it in back when half my colleagues were joyfully ranting about it, and truth be told, I put it off because I figured it'd be too hardcore. Not in terms of being too difficult, but in terms of feeling playing it successfully would need to be a second career.

Well, I broke the seal and now all I can think about is Dead Cells, so I was halfway right. Up until a few days ago, it had been The Binding Of Isaac that occupied my every spare-time thought, but Cells has neatly and completely supplanted it. Much has been made of Cells' tapping into Dark Souls and Metroidvania bloodlines, but, coming straight to it from Isaac, I can see just how strong that lineage is too. I.e. the combination of never know what you're gonna get with slowly increasing the total pool of available goodies, and finding that sweet spot that, though death is gutting, you're always highly motivated to try again immediately.

And that's the secret sauce here - you never feel that you've wasted your time, and the slow growth of both your own ability and the toys you can call on to survive your voyage through this eerie underworld means there is real conviction that next time, this time, you're going all the way.

This is one of those games that fits my lifestyle with almost creepy precision. The sense of accomplishment within a lunchbreak; the sense of going somewhere else; the sense of a story told only through implication around the edges; the sense that I will always pull a little more from it; the sense that it doesn't put a foot wrong in terms of controls and interface, so every failure can be pinned on me and me alone. A jigsaw piece that fits perfectly right now. Dead Cells is going to live in my head for a long, long time to come.

Graham: Watched in videos, Dead Cells seems like total chaos. There are mobs of enemies leaping and dive-bombing, thorns are sprouting across the architecture, explosions are popping constantly, and magic effects are whooshing this way and that. Yet it's surprising how quickly it becomes readable when you're actually playing it, even for an amateur like me. From my first few minutes with it I could see an enemy's pounce attack being clearly telegraphed, which meant I could time my dodge roll and attack it from behind. It felt methodical, satisfying - a feeling driven home by the sound and animation.

Then I'd advance and get overwhelmed. Too many enemies made for total chaos again. But I'd keep trying, and bit by bit those harder fights would come under my control. Drop a turret here; roll over there; spam grenades everywhere. Enemies would pop with a delightful squish, points would scatter across the gutstained floor, and I'd hoover it up gladly while rushing onwards. I love all the systems Alec and Matt outline above, but when it comes down to it, I'm playing Dead Cells for how good it feels to hit things. They mention Dark Souls, Metroid, Isaac, and I agree and would add Diablo to the mix.

It's also worth recognising something else: this is an early access game. Its systems have improved over the course of the past year, and the satisfaction of hitting things has been present from the first release. This isn't the first time we've awarded an early access game in the advent calendar - Kentucky Route Zero was our top pick, notably, with only three episodes released - but it remains a rare instance of an early access game that's worth playing immediately rather than holding out till it's finished.

Katharine: Dead Cells isn't normally my type of game. I bounced off The Binding of Isaac after about 20 minutes - not because of the gore but because I very much like games to have a beginning, middle and end that doesn't require me to start again every time I die - and I've more or less steered clear of the genre ever since. Dead Cells, however, has won me back.

It still sends you back to the beginning each time you shuffle off your mortal coil, but the way it banks and carries over unlocked items is a stroke of genius. It makes the whole game feel like more of a journey, and even if you do end up spending the vast majority of your time dying over and over again in the first three main areas (did I mention I'm also rubbish at these sorts of games too?), the progress you make and the cells you collect still feels like time well spent. The controls and combat are also super satisfying despite the fact it's still in Early Access, and its pixel art is just gorgeous. It's made me want to give rogue-likes another chance, and that's a rare thing indeed.

Adam: There were three games I'd gladly have put at the top spot this year: What Remains of Edith Finch, Divinity: Original Sin 2 and Dead Cells. Three games that'd be contenders in any year and all so very different to one another. There's the short-form narrative invention of Finch, the enormity and sheer mechanical density of Divinity, and the endlessly replayable combat perfection of Dead Cells.

My learned colleagues have already described its brilliance - the precision of the controls, the beautiful ugliness of its setting, the challenge, the unlock system - so I'd prefer to take a moment to recognise how rich and diverse a year it has been. Dead Cells is, even in its early access form, at the bleeding edge of a certain kind of design, but even though it's at the head of our 2017 table of honourables, it's keeping company with cousins many times removed. There were so many games to admire in 2017 and I expect we'll cast our net even wider in 2018.

Here's to all of them, with an extra special round of applause for Dead Cells, which takes the crown this year.

This year's list was compiled by collecting votes from Adam Smith, Alec Meer, Alice O'Connor, Brendan Caldwell, Graham Smith, John Walker, Katharine Byrne and Matt Cox.

In previous years we each compiled an unordered list of ten games to collate the advent calendar list. This year, each person was given ten points to spend as they pleased: if they wanted to give all ten to one game to make sure it featured, that was fine (no one did this); if they wanted to change their votes based on how the list was shaping up, perhaps to take them away from a safely included game and add them to something on the borderline, that was fine, too.

The idea behind this system was to reward more of the games that we truly loved. It encouraged people to focus on their true favourites rather than make the numbers up to ten just for the sake of it. And this way, a game that two people 'just liked' would not always trump a game that one person loved. If that love was strong enough, it could still get on the list. This system also works better at a time when there are more games than ever that only one person on the team has played, a reflection of both the increased number of games being released and the current team's wonderfully diverse tastes.

These changes are probably partly responsible for the games on this year's list surprising some readers. The larger part of that surprise was probably caused by Matt and Katharine, who joined the team late in the year and therefore hadn't already made their tastes known.

The initially compiled long list included eight games that didn't make it onto the final calendar. They were CrossCells, Everything, Heat Signature, Hellblade, Kingsway, Resident Evil 7, Rime and The Sexy Brutale. Each one of these games received one point; everything that was included in the calendar received two or more.

Edith Finch and Dead Cells received the same number of points overall. Dead Cells was chosen as game of the year after some discussion - though we can mathematically justify it by saying that more people felt strongly about Dead Cells, whereas the majority of Edith Finch's points came from a single voter.

If you're looking for more recommendations, we also published a list a few months ago of the best PC games ever. Only one game from 2017 made the list.

And that's it for another year. Thanks to everyone who read along across the month of December. The Advent Calendar will return...