Overthinking games: designing natural beauty in Eastshade

Room with a view

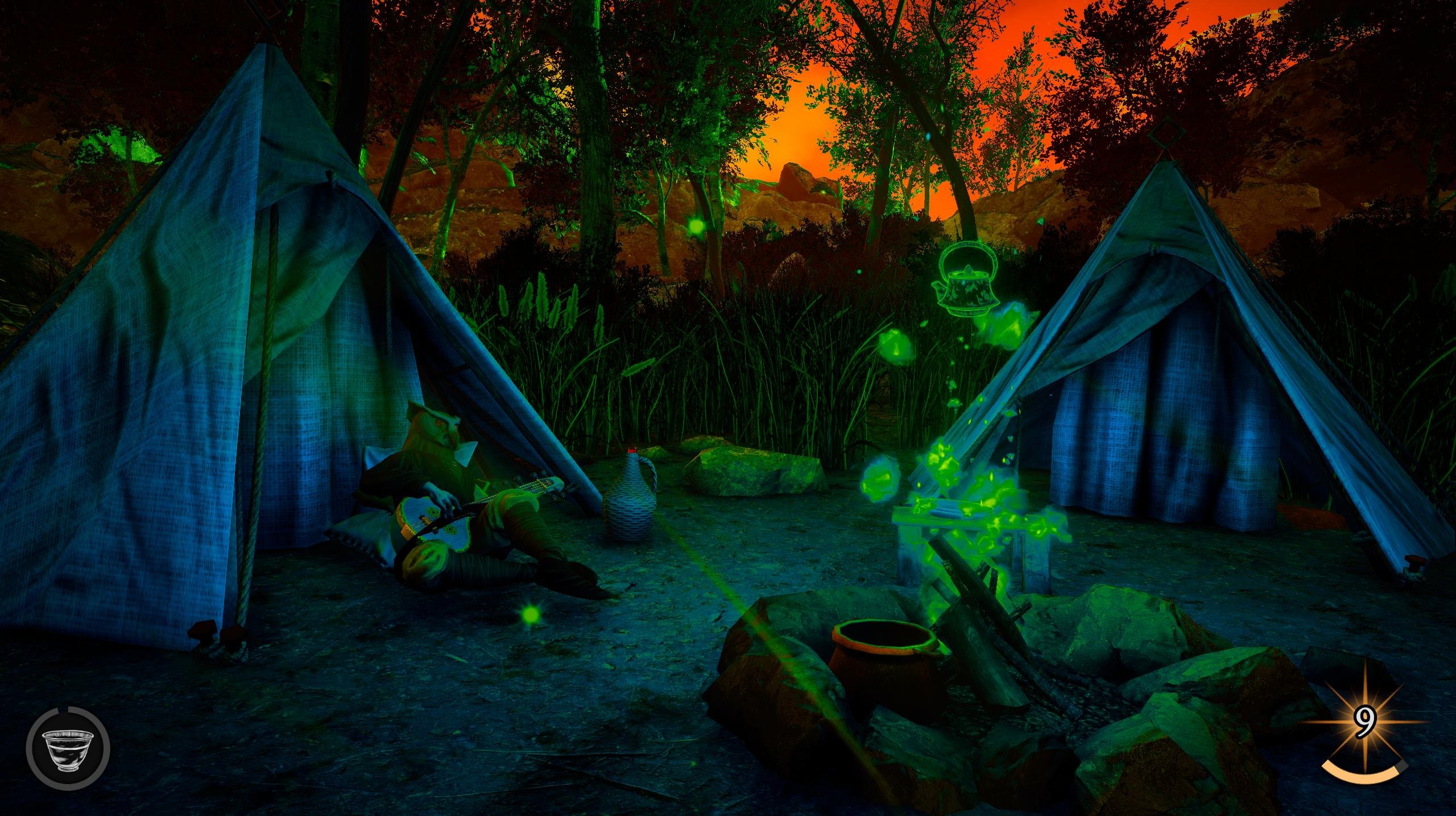

The first I ever saw of Eastshade was a single screenshot. In it, the sun stands high in the sky over a glittering river. Off in the distance, past the forest and its imposing trees, you can see what looks to be a city. Eastshade is full of such carefully designed landscapes: forests that invite you to saunter through them; buildings you just want to take a closer look at. Eastshade is a first person exploration game where every landscape looks like a potential work of art because that’s the game. Whenever you feel like it you can pop down your easel and start painting. How does everything look this nice? How to explain that almost everyone you talk to is equally impressed by what they see?

Instead of busily overthinking what makes me react so strongly to what I see on screen in Eastshade, I decide to enlist a professional and pose my questions to Eastshade’s lead developer Danny Weinbaum. He explains Eastshade’s strong sense of place is deliberate, and the result of the difference between traditional game design, and his own point of view as someone with a background in environment design.

“Most game designers approach environment design with combat in mind, so your environs have feature opportunities for cover or certain chokepoints. By contrast, I want to design the prettiest place I can think of.”

The actual process involves a combination of research and trial and error, on the hunt for slightly nebulous qualities that make creative endeavours so difficult to explain. “I strive to make something that looks good. To do so, I research actual architecture or building processes,” Weinbaum says. “Once you look at enough architecture, you definitely start to learn how things are constructed. You develop an internal library of architectural ideas to work with.”

Playing Eastshade, you can see different architectural influences mix together. Hobbit holes and cottages with thatched roofs blend with tall, plastered towers. Their big widows and intricate domes leaving a strong impression even at a distance. My suggestion that Weinbaum has “Frankensteined” real-world architecture to create something completely new startles a laugh out of him before he gently concedes. Eastshade lives from the bigger picture that emerges from paying attention to small things such as the trim around a window or the shape of a door.

As much as Weinbaum and his team populate their world with things simply because they like them, many design elements were also born out of the need to solve a problem. Such are the rice terraces near the city of Nava. While not completely unheard of, they struck me as an unusual design choice for a city by the sea. Rice terraces near the ocean are often at danger of fields being flooded with salt water. Here, they’re a way to fill up an empty hillside, both reasonable in scope and easy enough to create from a technical point of view.

Weinbaum and his team chose painting as Eastshade’s core interaction to give players a reason to explore the world and interact with its inhabitants. As travelling painter, you can either paint whenever you feel like it, or paint a commission to pay your way. Not unlike singing in Wandersong, you can use your creative skills to solve a problem or simply make someone’s day a little nicer.

Apart from offering combat-free alternative to roleplaying, Eastshade also wants to prove that a focus on exploration doesn’t have to make a game lonely or repetitive. When I tell Weinbaum how Eastshade feels very lived in, particularly because your arrival doesn’t lead to townsfolk immediately swamping you with quests, he stresses the importance of Eastshade feeling alive.

“There is certainly a fair share of indie games that are lonely places, and for good reason, but I wanted Eastshade to feel alive. Interacting with NPCs should be fun, like meeting new people, but your main reward isn’t necessarily satisfying their requests.”

Weinbaum puts it as “the place being the reward” – you look for ways to cross bridges or open closed doors, with the quests being instrumental in making you explore further and search for specific items to deliver or scenes to paint. But your role isn’t to save anyone, it’s to find a way to fit into a community and learn more about the people and landscapes that surrounds you. People continue their daily lives with or without your intervention.

Compared to a Bethesda game, where you’re the most important person in the entire world, Eastshade may feel like it doesn’t care about you. But every game makes allowances for the players moving around in it, and this is no different. In Eastshade this means having a clear path of approach to important buildings and towns, or simply not getting stuck in forest undergrowth. NPCS, too, are placed in a way that encourages you to talk to them. “It doesn’t hurt me if you don’t pick up on everything or miss a few quests, but if I notice people continuously missing whole areas or quests, that’s a design oversight,” Weinbaum says.

It strikes me as an art all of its own to design a place that doesn’t look like it’s made for your benefit, while being designed in so many small ways to be player-friendly. This includes Eastshade’s abundance of visually exciting ideas. There’s more to see than the real world could ever provide in one relatively dense area, and the distance between one place to the next, be it a mysterious cave or a tree so broad and lovely you just want to sit under it, is kept small enough that you don’t have the feeling of endlessly walking through empty space.

For once it seems like, even with all the overthinking, I couldn’t have considered all the aspects that go into an aspect of game design that’s easily taken for granted, from the lighting to each individual bush that someone placed in Eastshade by hand. The question that started my musings, however, turns out be relatively easy to answer.

“Why do a lot of people think Eastshade looks pretty? That’s human nature. Everyone loves a sunny day, the ocean or a nice forest.”

Duh.