Why you can anger the gods in Noita

Who wouldn't want to

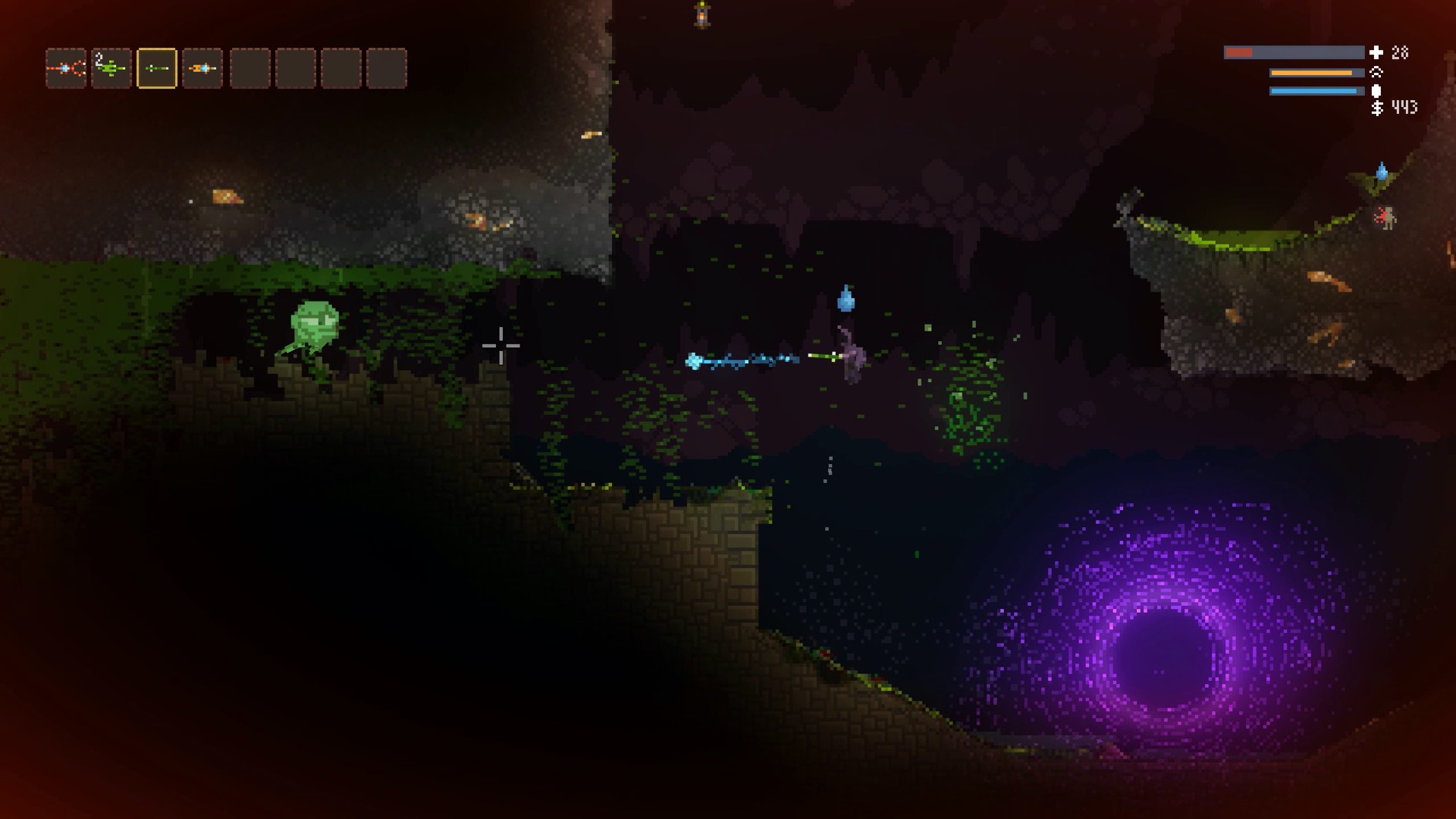

In Noita, you can destroy every pixel. Walls, lakes of blood, rock mass, bodies, piles of gold, wooden piles, minecarts - if it’s there, you can mess it up. But there’s one place where you probably shouldn’t do that.

The Holy Mountain is a moment of respite on your journey downwards in this very physical take on the dungeon-delver. It’s somewhere where you can recoup your health, buy new wands and spells, and prepare yourself for the next area on your journey into the depths. But if this sanctified place should become damaged, you’ve just angered the gods.

“I’d point out that angering the gods is probably one of the things that people don’t like about the game,” developer Petri Purho tells me. The problem, you see, is the worms. But there are many reasons why angering the gods exists in Noita, reasons which tap into the very bedrock of how the game works.

When you anger the gods, a large and dangerous skeleton guardian called the Stevari begins spawning in the Holy Mountain for the rest of your run. It’s there to dissuade you from breaking the walls of the Holy Mountain, but to understand why that’s important, you have to understand Noita’s roots.

Noita started not as a game but physics engine made by Purho. So the first challenge for him and his fellow developers, Olli Harjola and Arvi Teikari, was to find a game in which to use it. Developer Nolla Games started with a permadeath-based dungeon-delver which is actually quitte close to what it is today. But it had a big problem. While the engine’s physics created great interactions between objects, it also produced lots of glitches. “They were annoying and unfair, especially if you died because a box came flying out of nowhere and hit you,” remembers Purho.

Without knowing for sure if they could fully avoid these glitches, Nolla explored alternative game ideas that might mitigate them. One was a god game, which Purho describes as a side-viewed Populous, in which you’d control multiple units. The good news was that it wasn’t so much of a problem when one was flattened by a flying box. The bad was that since you weren’t controlling a single character, you didn’t tend to pay close attention to the world, making the engine’s banner physics interactions little more than a sideshow.

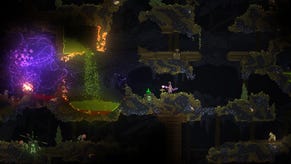

So they returned to having direct control over a single character, and began implementing a sprawling open-world game. Similar to Terraria, it would feature base-building and lots of exploration, but building on the scale of the engine’s pixels, rather than Terraria’s large blocks, was fiddly and unsatisfying, and playtesters kept getting lost and missing important areas. Nolla also wondered if they were getting the best out of its procedural generation if players only started a new game once or twice.

So, once the team finally resolved the physics glitches that were causing unfair deaths, they swung Noita back to permadeath, and they tightened the levels from an open sprawl into the narrower downward plunge that you play now.

It was in the Terraria version of the game, however, that Nolla built Noita’s first spellcasting system - or, as it was then, a sci-fi weapons system. Just as today, you could load its equivalents of wands with spells, but you could do this anywhere, rather than in prescribed areas. Enemies would drop spells, and you had large inventory for both spells and wands.

The wands were immediately fun, and the spells combined to create a vast possibility space of different effects. “It’s pretty big. We don’t actually quite know how big it is even now,” says Purho.

But the team noticed that players weren’t exploring the full spectrum. It turned out that giving players the chance to edit anywhere was a big problem. Along with the way spells dropped from enemies, it gave them the opportunity to quickly collect and set up a favoured set of spells and and they never really explored other creative paths.

There was a second problem. “It was also tedious because you were collecting all these spells and editing all the time,” says Purho. “In retrospect it’s obvious, but we were a bit lost, I guess.” After all, something else was contributing to the slow pace of the game: the health system.

The sci-fi setting evolved into one in which you’d be a vampire mage, and you’d recoup health by drinking blood. (Have you come across the Vampirism perk? It’s a surviving artefact from this period.) “That was fun, drinking blood and it’s going everywhere, and you could dig through bodies to get blood out of them. So it was a lot of fun in ways,” says Purho.

But it also meant that players played far too conservatively. “You’d constantly be editing, you’d get your optimal wand going, and then you’d be constantly drinking blood to keep your health up. You were in danger but not really.”

Nolla’s solution took five parts. Step one: remove vampirism (“It was a big thing for us, because we were losing this fun mechanic”). Two: limit the number of wands you can carry to four. Three: limit where you can edit wands. Four: make enemies drop gold rather than spells. Five: add a shop, where you can buy spells and recoup health.

Enter the Holy Mountain.

The changes showed immediate success: players had to get to the end of the level to heal themselves, and play during a level was only paused by meaningful choices over whether to carry one wand over another.

But though the game destroys its entrance when a player leaves so they can’t reenter, Nolla soon saw players getting back inside again. They were using their ability to destroy anything to tunnel back into the Holy Mountain at the top of a level and use it as a base: somewhere to store wands they couldn’t carry, and where they could go back to edit them any time.

“People who played the game the most used this strategy, and we worried it could become the default way of playing the game,” Purho explains. “It could be too tedious, so we decided to make it so there was at least a price to it. The price was angering the gods.”

Introducing the Stevari seemed a good solution. Purho wondered if the skeleton guardian could be tougher, but it was in good enough shape that they put Noita into Early Access.

And then they realised they had a problem with worms.

Burrowing through Noita’s world are packs of worms, which seek out such sources of food as the player and pools of blood, and they’re quite happy to damage the Holy Mountain with their tunnelling and thus anger the gods without any input from the player.

Noita’s forums lit up with complaints that the mechanic was unfair.

“But from our perspective, it was adding fun variety to the game,” says Purho. “The guardian isn’t that difficult an enemy because there are lots of ways of dealing with it, and it’s fun when you get this worm path into the Holy Mountain, because you can use it to go back inside. That’s quite a big reward.”

But Nolla issued a fix in the game’s fourth update in late October, placing a crystal beneath the floor which repels worms. It’s a solution that reflects Nolla’s naturalistic philosophy for the game: they could have made it so the worms can eat everything except the materials the Holy Mountain is made from, but they wanted it to be systems-led rather than down to an arbitrary rule. “It’s more interesting to have something that has an effect on the world,” says Purho.

The crystal works by stopping worms from considering players as food when they’re within the crystal’s radius of influence. So if another source of food is on the opposite side of the Holy Mountain to a worm, it’ll still eagerly churn its way through it and anger the gods, but the crystal markedly reduces how often the worms appear, and thus also the frustration.

“I don’t think our players are that vocal about it any more, so hopefully it’s not that big of an issue now.”

The reason Purho isn’t quite sure is that the worms only really annoyed a certain group of players. The more skilled the player, the less they cared about the worms. The players who complained most were mid-tier players.

Purho has a theory why. Worms are affected by gravity, so over time, they’ll make their way downwards. This means that the longer you spend in a level, the more likely it is that the worms have moved on or died before you reach the Holy Mountain. High-skill players tend to hang around a level longer to hoover up stuff, while mid-tier players tend to make a beeline for the bottom, just in time for when the worms reach it.

That’s Purho’s theory, at least. And if it’s true, there’s a chance that the reason the complaints have reduced is because mid-tier players are now simply better at the game.

But it’s hard to say. Skilled players, meanwhile, are causing other headaches, such as Purho’s girlfriend, who figured out a way of getting back into the Holy Mountain without angering the gods.

”She uses a teleport potion to teleport out of the Holy Mountain, skipping the trigger that destroys it. Then, if you pass the lava lake at the top of the Snowy Caverns, you’ll go back to the beginning, and then you can use the teleports at the bottom to go back to the intact Holy Mountain.”

But Purho is more bemused than he is concerned. “Doing it is a bit on the tedious side.”