Age of Wonders: Planetfall is about building empires in the ruins of an empire

A hex of one's own

Did you ever read about the Ship of Theseus? I'm sure you have – the RPS community is, after all, a bastion of scholarly insight, where people can write about things like digital museums and heraldic devices and attract comments like “actually, Liu Bei's supposed Han ancestry has minimal DNA basis and I'll thank you to use the Harvard referencing system”.

But on the off chance it's slipped your mind because you've been binge-reading Ibsen or whoever, the Ship of Theseus is a classic thought experiment. In brief, if you replace every part of Theseus's ship as the wood decays, is it still his ship? Are things no more than what they're made of, or does something about an object transcend its components? And what the hell does any of this have to do with Age of Wonders: Planetfall, a turn-based 4X strategy game featuring jetpacks and acid grenades? The answer to the last one is that there are Elves of Theseus, too. Also Dwarves of Theseus and Borgs of Theseus. Crikey!

Planetfall is the first game in Triumph's 20-years-strong empire-building series to embrace science fiction and venture beyond the atmosphere. In theory, anyway – you're granted a brief peek of the stars in campaign select screens before you're whisked off to another series of firmly terrestrial, hexagonal grid maps. As in previous games, the basics of play are raising settlements, researching technologies, balancing income and production, wooing rival civs and/or staving their skulls in on separately loading battlefields. There are population happiness and unit morale stats to fuss over, resource-intensive “Operations” (aka, spells) you can unleash to tip the scales in a firefight, and hero characters who factor into RPG-style quests that often double as tutorials.

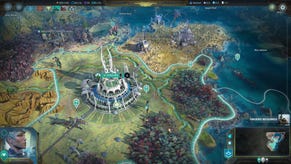

Triumph has made a few significant structural revisions to the elderly Age of Wonders 3 template. Maps are now divided into Sectors - small, busy clutches of buildings, hazards and terrain or climate effects, which makes the landscape feel more like a collection of places and less like, well, space. Combat, meanwhile, rests on a familiar balance of offensive, defensive and support unit categories, but takes a few extra cues from XCOM, with an overwatch mechanic and a corresponding emphasis on cover. There are also the new unit mods, hundreds in all, which add a creamy dollop of variety to a menagerie that extends from pterodactyls to quadrupedal robot tanks. There's plenty for a returning player to consider, however well-trodden Planetfall's lustrous, faceted terrain may appear from a distance. That said, during my few hours with a demo build I found myself less intrigued by what Triumph had added, and more by what had somehow remained the same.

Consider the six new races - all wrestling for the abandoned territories and riches of an interplanetary human empire called the Star Union, whose collapse presages the game's events. They may sound refreshingly weird if you're sick to the gills of Orcs and wizards, but in practice, each is its own little Ship of Theseus thought experiment, a collection of interestingly repurposed parts from previous games and SF&F generally. The Amazons, for example, are space elves whose rapport with nature allows them to field dinosaur cavalry and walking trees; being all-female, they supply the de rigueur sexy glowing-eyed lady for the cover art. The Deva, meanwhile, are “capitalist-communistic” space dwarves (confusing!) who wear giant mech suits (neat) and are partial to a spot of mining (of course).

There are two flavours of humans: the Syndicate or space mafia, who are great at trading and spying, and the Star Union's old Vanguard militia, the Americanised normies of Planetfall, who are great at catching opponents in webs of reaction fire. And then there are races that gently reinterpret other works of sci-fi. The Kir'ko, for example, are the Zerg with something of the snobby mysticism of Halo's Elites, while the Assembly are the Borg if the Borg could be persuaded to care about buttering up other rulers and signing trade deals.

Planetfall is very far from the first game to practise this kind of genre alchemy, and before we start yelling about diminishing returns, it's arguable that playing around with such archetypes, reinventing without destroying them, is integral to SF&F's appeal. As a man who has weathered more goblin charges than you've eaten hot dinners, I love the mild shock of, say, deploying a Kir'ko squad to find that they're not quite the buy-in-bulk swarm faction I imagined, going by all the talk of hiveminds in dialogue. True, their grunts receive defensive bonuses when they club together, and grow “frenzied” with every successive attack, but they're also pretty hot at sniping and warping flexible specialist units across the map in a cloud of insectile emissions.

These mild surprises owe something to a narrative that, its penchant for naff jokes and overwritten macguffins notwithstanding, is sort of about the construction of culture and identity. All the factions were once appendages of a greater (and crueller) civilisation, and are struggling to reorient in the vacuum left by its downfall. Inevitably, old sins and grudges have an out-sized impact, but the past doesn't have to determine the future. The Kir'ko were once the Union's slave workforce, and harbour an appropriately dim view of the humanoid factions, but reconciliation is a possibility. The Amazons, meanwhile, owe their elvish sensitivities to centuries of gruesome biochemical experiments: their ancestors were essentially Big Pharma, which rather undercuts the whole hippy-green-fingered vibe. The legacy-of-empire theme also gives us six “secret” technology trees, one per race, which call upon the Star Union's most terrible enigmas, and unlock the nastier victory scenarios. If befriending neighbours, out-producing everybody or scooping up every last colony isn't your bag, you might incinerate the planet's surface from below or obtain limitless energy via portals to other dimensions.

It's an opportunity to think twice about the social and racial stereotypes SF&F games reflect, and too often perpetuate – what does it bode, for example, to cast this world's quasi-American faction as an army that no longer has a nation to defend? Planetfall may not deliver useful answers to such questions – it's a game about having fun building an empire, for crying out loud, and its characterisation of former slaves as a well-spoken religious tribe risks channeling any number of racist cliches. But I like that it encourages me to ask them, at the level of both writing and mechanics.

So, in a much smaller and sillier way, does the new modding system, which lets you pile on attributes such as micro-missile arrays or phasing gadgets that teleport you away from damage, steering faction characterisations still further from type. Is an elf still an elf when she has robotic legs? The copy-pasting of more basic technologies between races, on the other hand, seems a little contrary to the theme, though each race does have access to its own unique combination of weapon and ability types. I appreciate that it would have been a nightmare to design and balance six wholly separate research trees, but it's harder to feel the difference between space marines and telepathic insects when everybody has access to the same, generic “civilian infrastructure” upgrades.

Planetfall is not the absolute reworking one might hope for, from a venerable classical fantasy series making its first trip to the stars, but there's a lot going on under the crust. At its most powerful, its portrayal of a postcolonial galaxy reminds me a little of Sins of a Solar Empire – there's the same sense that everybody involved, righteous or unrighteous, is fighting the gravity of an underlying, aeons-old corruption. Beyond that, its battles are ripe with variables to meddle with, and the newly region-centric approach to map design feels like a good advance on its predecessor. It might be broadly the same old ship dipped in chrome, but I look forward to taking it out onto the water and seeing where it goes.