Eidolon Diary: Diarising Eidolon

Surviving & Journaling

Eidolon is a beautiful survival game inside which John starved to death on video back in August. We asked Jack de Quidt, writer for The Tall Trees, to live a little longer and write a little more about his experiences with the game.

When you first open up your journal in Eidolon you’re met with wonderful, terrifying blankness. You have no objective. You have no map. You have nothing in your inventory. There are spaces for these things, but they’re utterly empty. One icon in particular drew my attention - a little hand-drawn pencil that opened a tab with a single blinking cursor. I closed my journal. I looked out at the landscape. I opened my journal again.

I find myself in a dreary and beautiful landscape of which I know little about.

Eidolon is a game about uncovering mysteries. It disguises itself as Proteus, perhaps as a survival game in the vein of Day Z, but at its heart it’s something unique. It’s Candy Box, it’s A Dark Room, it’s the discovery of secret doors in houses you thought familiar. This means there are going to be some minor spoilers, though I’m going to keep almost all of its surprises secret. I walked down the hill.

At the base of the hill is a quiet lake.

I’ve found a fishing rod. Who left it beside the lake?

I wasn’t role playing - as it stands there are around 70 in-game pages of notes and none of them talk about how wet my feet are from walking through the marshes or how good blackberries taste. Instead I tried to take notes based on how I was feeling, sitting late at night on the floor with some beer, a proxy explorer. That’s why, occasionally, we get notes like:

I ate 40 blackberries by accident.

Because I did.

Eidolon’s survival mechanics are, for the most part, pretty gentle. They’re the punctuation as you move through the world, stopping occasionally to make a camp -

Startled by the rediscovery of my own campfire.

- or catch some fish:

Awoke to beautiful blue fog. Could barely see other side of Lake. Fished, cooked fish.

Occasionally my notes become slightly panicked as I run out of stuff to eat, but in comparison to other survival games which essentially hit you with a hammer as soon as you get a little peckish, Eidolon taps you on the shoulder and says “how about a snack?”.

Need to head south over a mountain to another lake, then southwest from there.

Eidolon revels in walking and exploration. The gameworld is enormous, with distances rendered comparatively realistically. It takes a long time to get from one place to another, and probably the majority of my notes are about my struggles and processes to get to where I want to go.

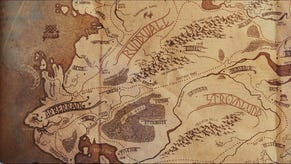

I’ve found some sort of map, hand drawn, of the local area.

The maps, and there are several, are all diegetic. You don’t appear on them at all, instead having to work your position out through landmarks and lakes and the bands of rolling hills.

I believe I’ve found my location on the map. It is getting sunsetty. My plan is to follow the river down from the easterly lake I am at to goodness-knows-where.

My heuristic at this point was to pick an interesting looking place on the map and go there.

Still raining. A little hungry. Will eat a fish.

It was beautifully mundane. The world is gorgeous, pastelly and impressionistic - fat polka dot clouds scud gently across vast skies, forests roll away into darker forests.

The pines I saw looming on the mountain descent were small, perfectly shaped pine “bushes”. They are cute and small and I wish I saw more of them.

Sometimes I encountered things in the wilderness.

An object on the ground some distance away.

Sometimes my discoveries were fun.

It was a little fox! Maybe this was the coyote I heard. I am reassured and starving.

Sometimes my discoveries were assuredly not fun. One of my notes just reads:

i got attacked by a horrible cat.

(I never encountered Horrible Cat again. There was, however -

Saw a bear and ran away.

And -

I can see either a deer or one of those Horrible Cats some distance ahead. It certainly has hooves. I don’t think Horrible Cat had hooves.

It’s probably still waiting for me.)

The primary antagonist of the game was (and still is, it hasn’t changed) The Spectre Of Getting Lost. Lots of games have tried to nail Getting Lost as a mechanic, but I’ve never seen it achieved as comprehensively and terrifyingly as in Eidolon.

I think I’m walking back towards where I began. This had better be worthwhile. I do hope I haven’t read the map/compass wrongly.

Cartography is not my strongest suit.

When I start descending I’ll know for sure I’m on the right track.

Concerned I’m reading my compass wrong.

I became obsessed with my inability to read a compass.

I don’t think I am. I hope I’m not. Will double check.

Checked again, definitely heading in the right direction.

That occurs seven notes before:

Fear I’m off track in a big way.

I imagine that to some people this feels too much like a chore. I’ve always loved maps inside and outside of games and the idea of treating an open world as a great spatial puzzle was what first drew me to Eidolon. Besides, when it pays off, it pays off magnificently. Burying yourself in a landscape, muddling and calculating and inching your way through it means that when something even slightly amazing happens, it’s A Whole Thing.

Oh my god the stars have come out.

At night I’d often set my course with the compass and walk looking directly up at the sky. Occasionally I’d pass beneath the canopy, or under the branches of tall bushes before emerging out into a clearing with the stars arching wide above me. Your first night in Eidolon, Horrible Cats permitting, is a certified Video Game Experience.

But even still, this isn’t Eidolon, not yet. What exactly the game is unfolds itself to you piecemeal, each revelation arriving just before it feels you’ve been exploring too long. Your first clue comes when you open your journal and find that alongside your paper notebook is a slick grey tablet like thing called a Luxe Device. It has a little signal indicator in the top left that (as far as I can tell) doesn’t seem to change and ostensibly seems to track your status effects. It’ll tell you when you’re hungry, or too cold, or ill.

Emblazoned in the centre of the device, though, is a warning that says “Due to your distance from a beacon, your vitals are subject to extreme changes, including death”. No context is given, but the first piece of the puzzle is already nestled within your journal.

The inventory objects that I acquired at the start of the game were represented in the world as tiny white glowing cubes, hovering at eye level. Collecting one gave me a fishing rod, or a compass, or a bow, or:

Binoculars! There were binoculars on top of the watchtower. I am so happy about this.

The first time I saw a green cube, then, I wasn’t sure what to expect.

Two flashing lights. Strange bird sounds. One of the lights looks green - perhaps another map?

The lights are opposite each other across a small cold river.

I picked the green cube up.

A letter. From the year 182.

Letters, let’s be honest, have existed in games before now. Most recently, Gone Home basically put us down in a Letter and Note Storage Facility and let us go wild. What struck me most about this was not just its rarity - I’d already been playing for an hour and a half, quietly exploring - but its style. The letter begins:

“Its been half a moon sins we left our blood in the storm & shadow of nite…”

It continues, introducing new ideas so thick and fast that my notes afterwards struggled to keep up.

Somebody fleeing some other people, a community, her name’s Ada? In a group with others. She’s tracking myths or stories, can’t find any in the ruins (?) that she finds.

This is a lot of new information to me.

She says she’s heading west to find “great skeletal leviathans” in the hope that they “hold their answers”.

The difference that this immediately made on the landscape around me was profound.

The landscape has changed now, knowing of skeletal leviathans and people fleeing others through these pines, down this river.

A couple of pages later I write.

Concerned now by the noise and light my campfire makes.

Below the letter in my inventory, I found two small buttons. One said “Ada”, and one said “Oldtown”. Clicking each button caused a glowing light to be emitted, presumably from my Luxe device, and go dancing off among the trees.

It took me a long time to work it out - Eidolon’s world is so vast that testing theories takes a while - but these green lights lead you to the nearest relevant thing within the world. Each discovery you make has similar keywords, and as the world around you blossoms with narrative you pingpong around the map from character to character.

A house, completely swallowed by blackberry bushes.

There’s so much I wish I could tell you, mundane and exciting. The moment I realised that the clock on my Luxe that I’d been navigating by had been entirely broken all this time. When I saw that my map had writing on it, among the trees.

When I caught sight of - something - vast, colourful, game changing through the darkness ahead of me. When I read about the cats. When I found the bridge. Danica Hemberly and Anders and MHZ and #FiveYearsGone.

But I can’t - I can’t because to talk too much about them would be to rob this wonderful, strange game of its power, and also because I am still so far from finishing it. Last time I played, the game’s plot took a swerve to a place that I would never have guessed, but looking back seemed entirely plausible.

When you sleep in the game, you dream about eidolons. Every night. These dreams manifest as four line stanzas drawn at random from Eidolons by Walt Whitman.

Dreamt of earth eidolons.

say my notes, and the next night I close my eyes and, in stark letters on the screen, dream:

“Of every human life,

(The units gather'd, posted, not a thought, emotion, deed, left out,)

The whole or large or small summ'd, added up,

In its eidolon.”

Jack de Quidt is a writer and composer for The Tall Trees and co-creator of Castles In The Sky, a videogame wot RPS has written about previously.

You can read more Survival Week articles over here.