How Hypnospace Outlaw's 1990s internet was made

*screaming dial-up noise*

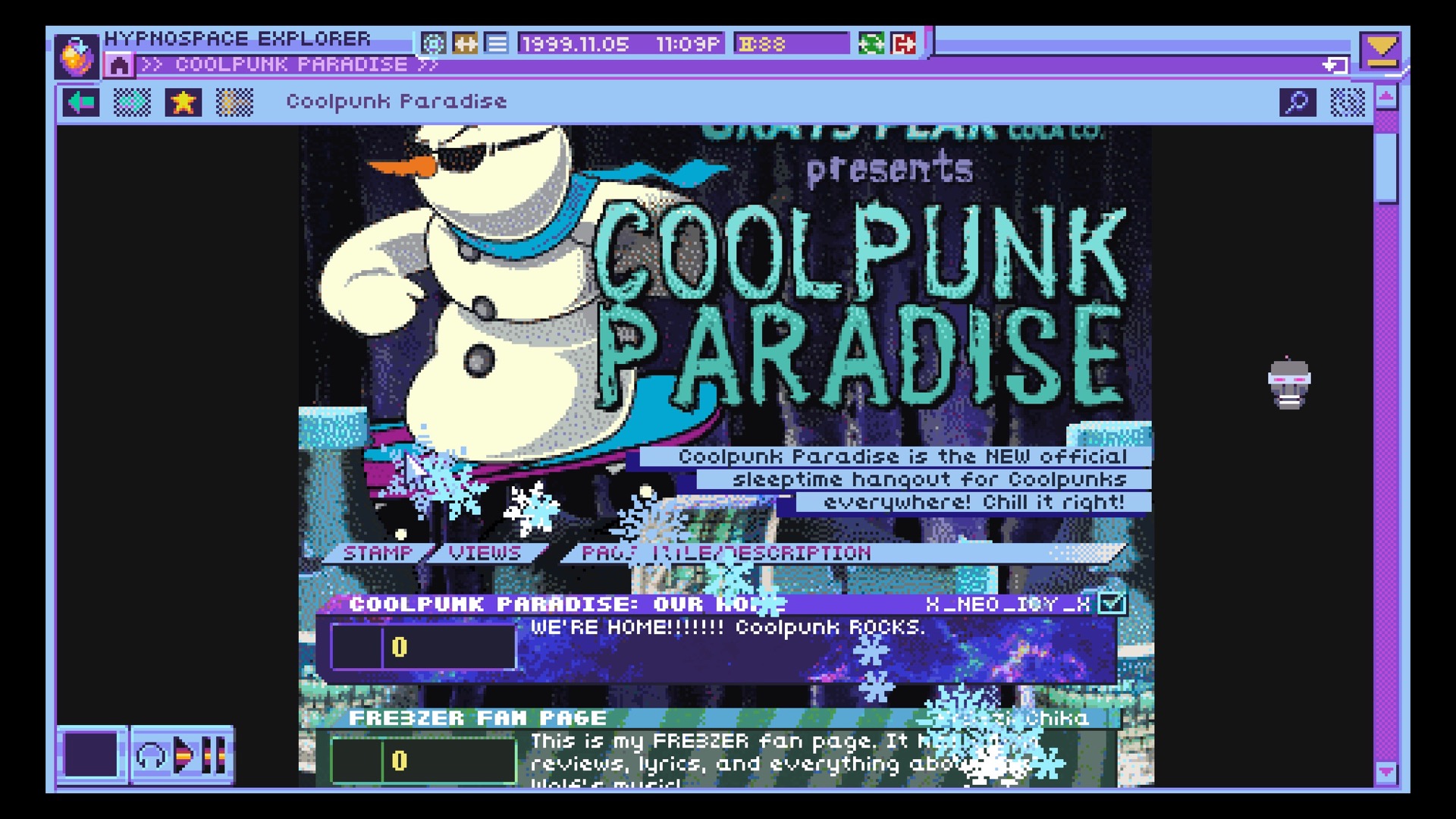

Hypnospace Outlaw is a game about surfing a fictional 1999 internet, a web of GeoCities-like pages made by a community of weirdo artists, rock stars, scammers, edgy teens, pastors, hackers and spiritualists. It’s funny, bizarre, poignant, and sometimes dumb, just like the early internet that it spoofs.

But it’s also a game, so its wild thickets of pages, all written by distinct personalities, are also navigable and carefully laced with puzzles to figure out. How did did the three-strong team behind Hypnospace Outlaw make something so playable out of something so chaotic? The answer lay in looking at how the early internet worked.

It’s 1999, the cusp of Y2K, and you work for a software corporation called MerchantSoft. As the maker of a walled garden of websites called Hypnospace, MerchantSoft imposes a lot of terms and conditions on its users, and you’re one of its enforcers, policing its rules, from content infringement to profane activity.

In other words, you surf an artificial internet where clues to finding the things you need could be anywhere. But for Jay Tholen, the creative lead behind Hypnospace Outlaw, it’s critical that this internet feels real and fun to read.

So how to help players get around? Tholen tells me that the first, and most obvious, thing to do was to create a homepage directory. Back before Google’s magical search opened the web up like a scalpel, you needed directories to find good stuff, so places like GeoCities had Neighborhoods, where you’d find science-fiction and fantasy pages in Area51, games in TimesSquare, and music on SunsetStrip.

“It had nothing to do with the game design, it just had to be in there,” says Tholen. After all, Hypnospace Outlaw came out of his fascination for the nascent internet. “That whole era, those were my formative years. I was 12 in 1999, and that’s when we first got the internet at my house. I was a little disappointed, because I was thinking the internet was Lawnmower Man and people flying around and conversing in 3D space. You were sold this utopian vision, this Epcot thing, where people from Australia and everywhere were hanging out.”

But while much of Hynospace Outlaw is closely inspired by how the early internet worked, it’s still the product of many decisions. For example, he’d originally wanted the directory to be set by the characters who created Hypnospace’s pages. But players might not immediately understand the esoteric thinking behind user-defined collections of pages. “It loosened the rules on what players can expect to find in any given place.” So instead, he had MerchantSoft dictate ‘zones’ with a bland corporate logic - Goodtime Valley (“Remember the good old days?”) and Teentopia Paradise - that players can immediately recognise.

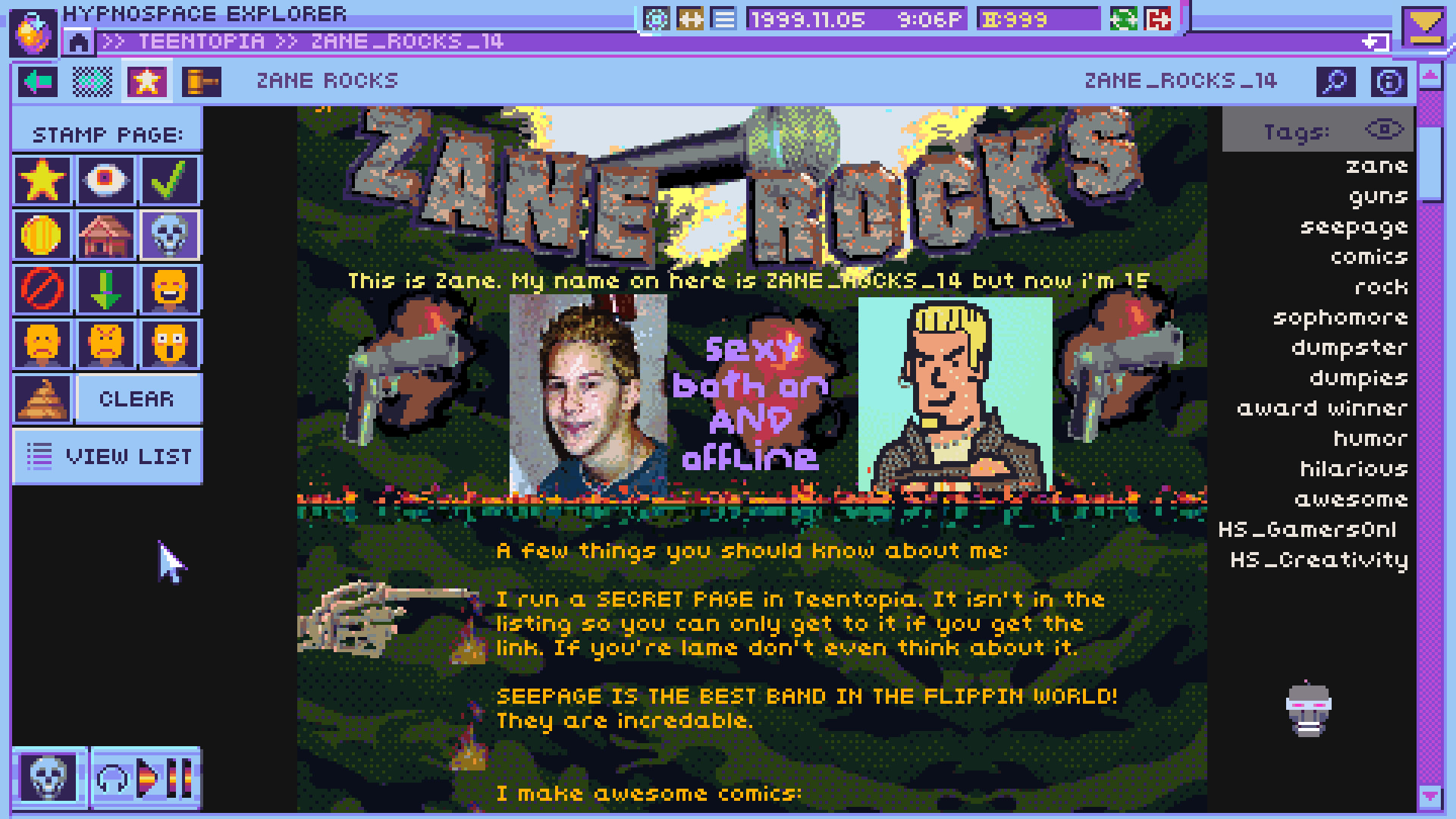

This, Tholen realised, naturally opened up possibilities for puzzles. Much of Hypnospace Outlaw is the result of design-serendipity like this. He saw that MerchantSoft would try to crack down on pages that feature content that doesn’t fit their category, and so users might try to hide pages to get around the rules, all the better for a player to try to find them.

MerchantSoft thus couldn’t be the only route into Hypnospace’s superhighway, so there are other ways to discover pages that users didn’t want MerchantSoft to know about.

A major way is by using tags and ‘clubs’ such as HS_Goofs-n-Laughs. Click on one and you’ll get a list of all other pages marked with it; they work a bit like the webrings that bound early websites together. “Since there are some unlisted pages, it was almost another overlapping circle of things you can explore outside the MerchantSoft-made zones,” says Tholen.

And then there’s text searching, which Tholen was nervous about because he saw testers ignoring the search box at the top of the in-game browser app. “They didn’t trust that it functions like a real OS would.”

What’s more, with a lucky search, players can stumble on things intended for the later game. “People found out quite a few sequence-breaks, sometimes by accident, because they guess things to type that I hadn’t thought of.”

Partly to address this, the game gates off pages according to where you’ve progressed in the story, and how many jobs you’ve taken from MerchantSoft: you can’t search for pages within zones that MerchantSoft hasn’t yet assigned to you.

But the gating also helps keep Hypnospace manageable for players. “It’s just super overwhelming,” says Tholen. “Even with the three or four zones you have at the beginning, people seemed to feel a little overwhelmed.”

Outside these formal ways that Hypnospace is organised, Tholen also designed informal ways to connect pages: linking them through stories and relationships between their makers.

These links grew and developed as its puzzles evolved. For the first year and a half, Tholen only made one puzzle, the early Gumshoe Gooper one, in which you have to find pages that illegally use images of a copyrighted cartoon fish.

“There was no consideration for what the puzzles were going to be yet, or what information you needed to know,” says Tholen. “We just made a bunch of content first. It’s probably not advisable to do that!”

But as a mass of pages built up, Tholen began thinking about the characters who authored them and their relationships, and for inspiration he looked back over the GeoCities archive oocities.org to see how they’d link to each other.

“It felt like archaeology, and also a game. I found a person who had a GeoCities website about Andromeda, but I couldn’t really tell if it was sci-fi or about the galaxy because it was so weirdly laid out. Then I saw a link to a completely unrelated page of an artist from Slovakia who does postmodern sculptures. I wondered why they were related, and then I saw him mention the name of the lady who does the art, and realised, oh, that’s his wife, and then back on her page, right at the very bottom, there’s ‘Designed by’ and it’s that guy. So you discover this relationship between these two websites.”

The team effectively built up lore around Hypnospace’s users, little details for players to notice that build links between them, and also help to point players around.

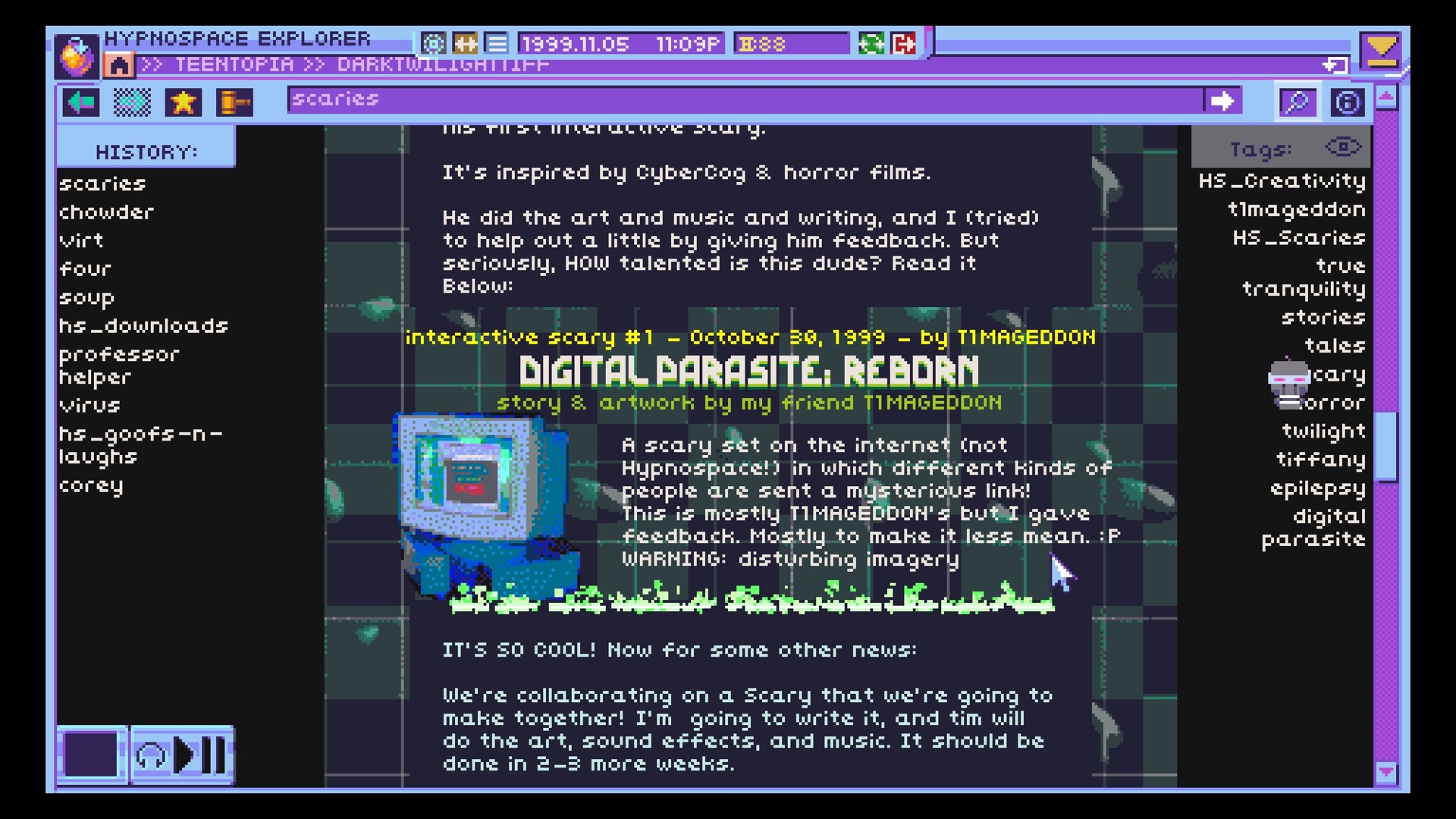

“So there’s this group of people who makes Scaries, which are like creepypasta things but a little more goofy and Hypnospace. One person made a really ornate one and I realised that its art style looked a lot like some art I did for a hacker character. So I made it so it was a collaboration between them, and then made them have more of a relationship. It was a little haphazard and very iterative.”

It helped that he could see what testers searched for. Tholen made sure that the most common searches would always return results (though not for the remarkably high number of tester queries for Limp Bizkit), knowing that for a lot of players they’d be their way into various puzzles.

Some pages were specifically made for a single puzzle, such as What In The World?, page about tech, which Tholen made because too few testers were figuring out the puzzle through the intended means. So the page’s author talks about how to make a secure password, which acts as a formula to figuring out his own password, which is the object of the puzzle.

“For some reason, as long as the characters feel like they’d say the things they say on their pages, players never seem to notice or care that it’s so in your face,” says Tholen. “Another thing we did - actually, this could ruin it for you a little bit! - some pages have flashing elements. Of course, having flashing text is a gaudy internet thing, but I made sure that in Hypnospace, it’s probably something you should read.”

And maybe gifs of revolving skeletal hands could also point at important stuff?

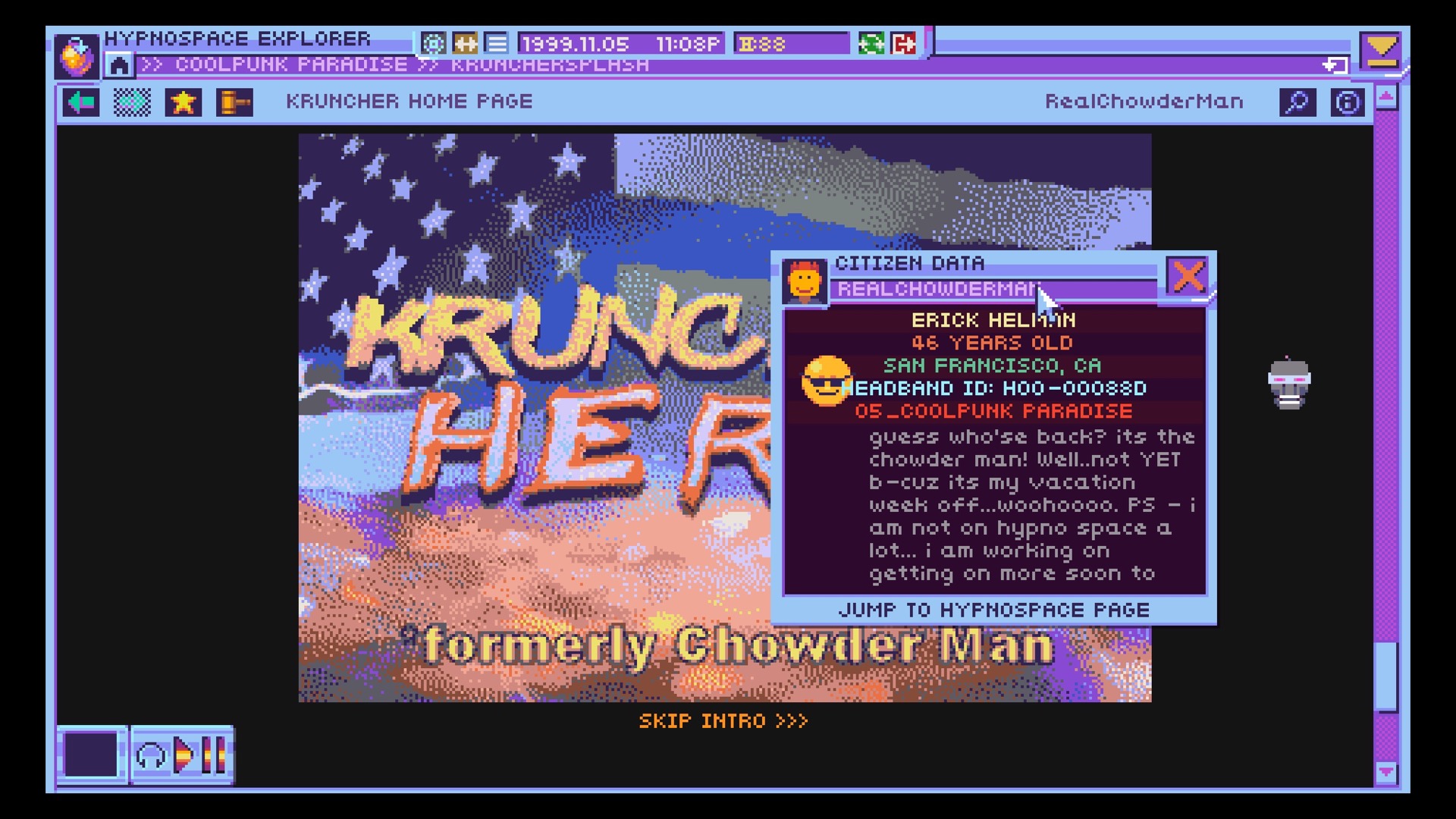

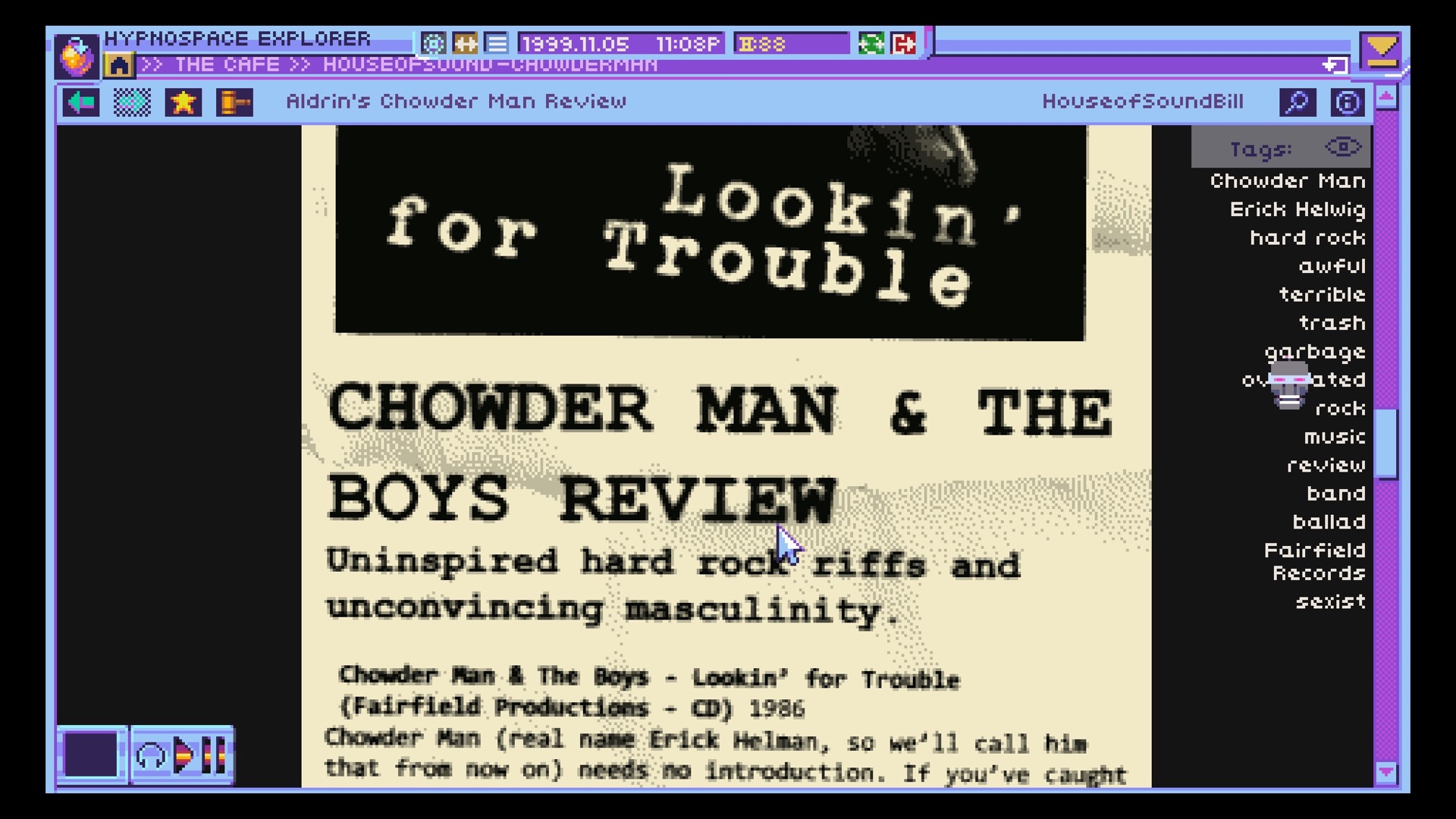

“There are skeleton hands pointing at important things! And also non-important things, too. Most dumb ideas we had, you can excuse their existence because it’s the 1999 internet. We have Chowder Man, this Kid Rock-type guy, and he was just going to be there in the background. But as Hot Dad [comedian Erik Helwig, the musician and likeness behind Chowder Man] sent more songs, we were like, we’ve got to make people listen to this stuff!”

So a story was written for Chowder Man, even though he wasn’t meant to factor into any puzzles. “I wanted players to be able to discover things that they weren’t pulled to through the cases, because it’s exciting.”

But then Tholen had to cave on that hope in the final few months of development. It turned out that almost no testers were seeing this extra material, because nothing was pulling them to it. So he had puzzles pull in pages like those about Chowder Man, just so players would see them.

“As a team we were a little worried that it’d feel forced. But either people detect that and appreciate seeing the funny stuff, or they just don’t notice. No one really cares, so I’m happy with that.”

It was a similar case with the applications you can download and run on Hypnospace Outlaw’s computer desktop. Early in development, Tholen thought, “Wouldn’t it be cool if there’s a soundscape generator?” And so the Hypnospace OS got apps.

The soundscape app is otherwise purposeless, but other apps do figure into cases, such as one which involves following a community of users who share encrypted music and other files. But how to open them? The answer involves a lot of searching and sleuthing and eventually downloading an app that MerchantSoft would never suspect.

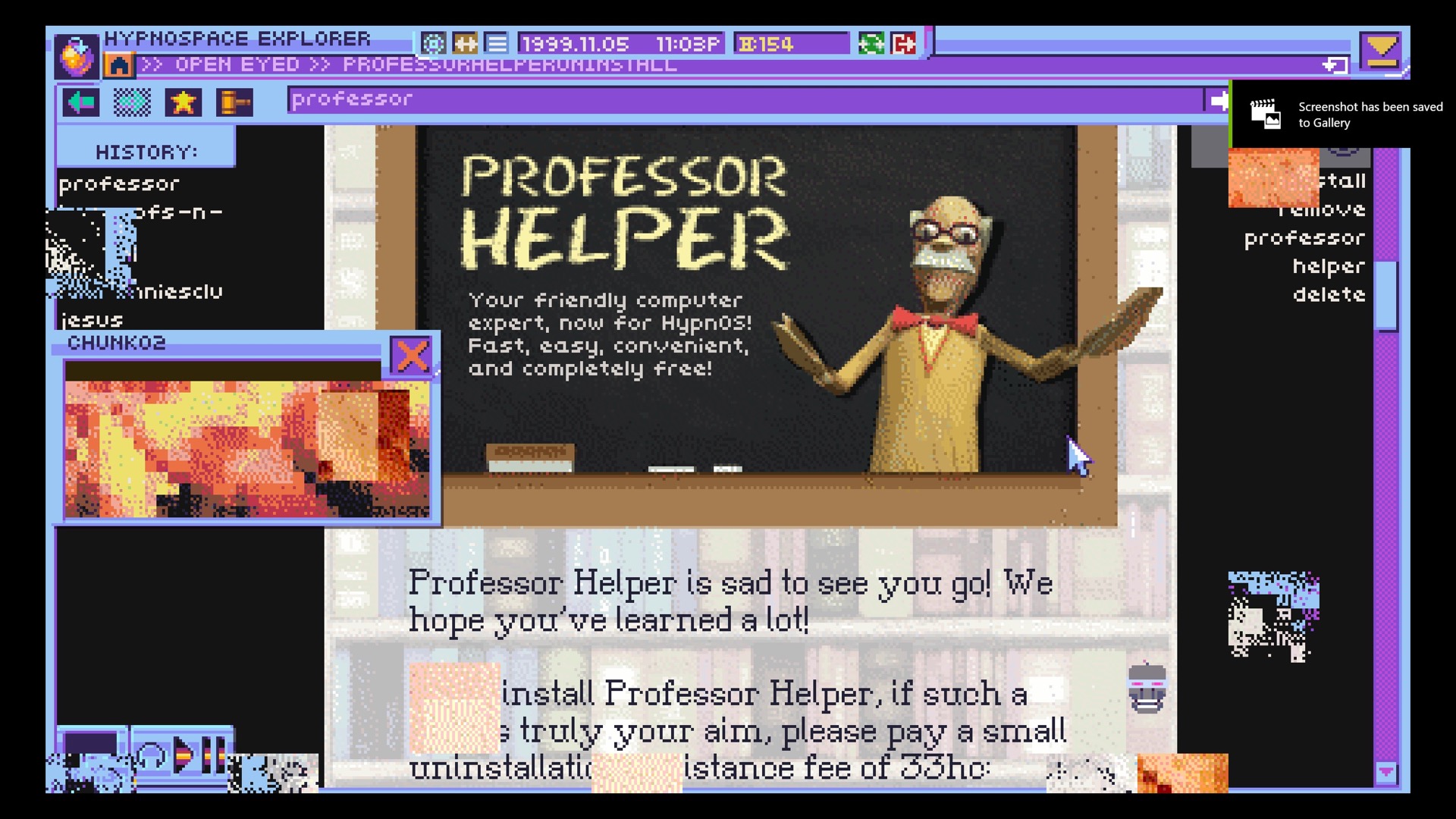

Other apps were destined for greater things, such as Professor Helper, a Clippy-like fun-irritation which is key to the game’s story but is loaded with way more functionality than the team managed to actually use. “We spent two weeks on coding in hooks so he knows what you’re doing, if you have the downloads manager open or whatever window is in focus,” says Tholen. “But we never did anything with it, so he just shows you ads.”

He’d like to release an update, though, and in it, he’d like to have MerchantSoft buy Professor Helper, so he starts wearing its logo on his shirt and showing you their ads. “And he’d also respond to what you’re doing in some other non-helpful way with documentation that reads like a intern wrote it.”

Professor Helper is a model for the wouldn’t-it-be-cool-if attitude that kicked off Hypnospace Outlaw: the will to embody late-1990s computers, and the iterative process behind the puzzle-design and storytelling that binds it all together. Making Hypnospace Outlaw was as wild and organic a process as that which lies behind the real web it parodies.

Disclosure: Xalavier Nelson Jr. sometimes writes for us, is one of the devs of Hypnospace Outlaw.