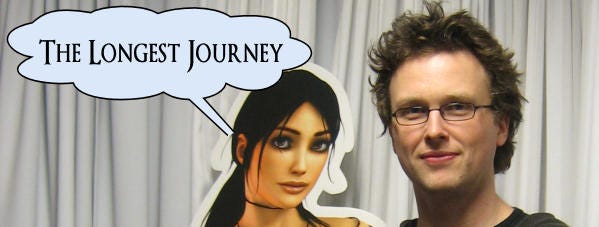

Ragnar Tørnquist On... The Longest Journey

In part two of our interview with The Longest Journey creator, and project lead on The Secret World, Ragnar Tørnquist, we get down to discussing The Longest Journey and Dreamfall. TLJ is a game that’s very special to me, and one I credit as having affected my life.

What follows is the most involved discussion of the game, and its sequel Dreamfall, I’ve seen from Ragnar, talking about the philosophy behind the game, the messages it contained, what it’s like to have aged ten years and reflect, and not least the news that The Longest Journey started life as a platform game. We’re joined by Dag Scheve midway through, which derails the conversation impressively. And if you look carefully, there’s also some more exclusive snippets about The Secret World hidden in there.

RPS: How old were you where you when you started developing The Longest Journey?

Ragnar: I was 25.

RPS: So pretty young.

Ragnar: Yeah. We’d wrapped up Casper, and shipped late – the story of my entire career. I was between projects, and at that time Funcom was deciding that working for hire… we were never going to keep our heads above water. So we decided to make our own games. One of them was going to be an online game, which became Anarchy Online. And the other was Project X. We had a Dublin office back then, but the game they were making died. But we liked the ideas there – two realities, one science fictiony, one fantasy. So I said, let’s do something with that: two worlds. And here’s the funny part: that game started off as a platform game. Do you remember Heart of Darkness? It was all the rage at that time. I was not a fan. I did not want to make a platform game. I wanted something else – I wanted to create this really interesting universe, and have characters you could interact with. And I loved adventure games. At the time, one of my favourites would have been Gabriel Knights. Oh, and the LucasArts games – Day of the Tentacle would be my favourite game of all time. So if I get to make anything I want, I want to make an adventure game. The genre was definitely beginning its decline. But I thought, screw that! I wasn’t as commercially orientated back then as I am now. Nobody was standing in my way, so I just did it.

RPS: This is why you have succeeded in life. You recognise DOTT as the best game ever.

Ragnar: I started building the idea of the game about a single character. A character that was known from very early on – long before the game had a title – as April Ryan, in a world that was dystopian and dark and depressing. She then travelled into this beautiful fantasy world. It’s interesting to look at the original design documents and see what changed. April was living in the Borderhouse, in this wasteland of a city, always dark – a very Dark City vibe. We watched that when making TLJ. April was having dreams of these dark angels. That’s how it started.

RPS: Why did it lighten from this dark beginning?

Ragnar: I realised that the game wasn’t really about a terrible world and a beautiful world – I realised it was more about the balance between these different elements of the universe. You wouldn’t make one of those sides a terrible place. You’d just make it different. And if you’re going to get into April’s life and enjoy her existence, which is crucial for understanding when her life is turned upside down, she has to have a life which is appealing. It’s a traditional story: you have a safe environment, you have characters who’ve never really experienced anything who are suddenly thrown into these situations. When I first realised that was the direction to go, I was thinking of putting it in the modern day rather than the future. But at the same time, to show the contrast between magic and technology, that might have worked better by setting it in the future. I was always torn between the two. Sometimes I wish we’d done it modern day, but other times I’m happy with what we did. So that was it. It wasn’t ever about finding out that there’s a heaven compared to this hell, but finding out that there’s a balance. Once you’ve realised that, then everything changes.

RPS: So you’re pleased with that change in direction?

Ragnar: I think it was the right decision. People are so sick of these dark, dystopian futures. Bladerunner’s still a fantastic piece of work, but that’s Bladerunner. Everyone else is doing exactly the same thing.

RPS: I recently played TLJ all the way through for the first time in years, and weirdly I’d forgotten that it was set in the future.

Ragnar: Yeah – that reflects the conflict I had within myself, and also the art director who really wanted to do it in the future. I always tried to pull it into the present day, and visually, he tried to pull it in the other direction, which has worked out really well. I’m not a big fan of things that aren’t recognisable on some level. I really wanted to say, “This is a place that I can understand,” and then bring on the fantasy. We did this especially in Dreamfall – bring everything down to the simple life, make it something you can empathise with. Especially with Venice in TLJ. It was modelled after East Village, where I’d lived in New York City. I wanted that atmosphere – a sort of funky, cool place that’s homey and villagey. And then bring on the skyscrapers and the spaceships.

RPS: This is a constant rant of mine. Games forget to ground you before spinning off into fantasy. Why do so many games forget this? The opening of Half-Life was so brilliant, and I don’t understand why everyone doesn’t do that.

Ragnar: I don’t understand! I love games that make me feel like I’m living a normal life, and then BAM, things change. Movies do that so well. Even big action movies understand this. Why don’t people do that any more? I agree.

RPS: Regarding Stark and Arcadia [the two worlds in TLJ], I think it’s impossible not to see it as commentary on the world we’re living in. Stark appears to be a satire of Capitalism. Was there a commentary you wanted to make?

Ragnar: Yeah, I always do. But I don’t try to push it into people’s faces. I’m a different person now than I was back then, that was a long time ago.

RPS: I found that too, playing it again. I’m a different person than the guy who first experienced the game.

Ragnar: That’s something I was able to emphasise with Dreamfall. With TLJ it was something that emerged as we made the game. I’m not sure the statement in TLJ was very clear or direct, and I’m not sure I want to say, “This is what we tried to say with it.” I try to put a lot into it, in terms of what my own beliefs and personal conflicts are, and leave it open for people to interpret.

RPS: Like what?

Ragnar: Like referring to religion in TLJ. Games don’t often refer to religion. I was trying to make the whole idea of that universe co-exist with religion, having that story in the context of faith. Because obviously TLJ is a game about faith, and Dreamfall is even more about faith. To the effect of having a character called Faith. The Longest Journey is a game about finding yourself, and having belief in yourself, and conquering your personal demons, on a very simple level. It is also a game about having faith, and you have all these characters, like the Catholic priest, having him refer to the whole aspect of faith in relation to the unbelievable nature of split universes, and how you reconcile that with your own personal faith. April is discovering that as she goes along – that to me is the core of the story.

And you’re right – it’s a heavy satire of corporate society, and the media. I think in TLJ it was more in pieces, whereas in Dreamfall it was more reconciled with the whole game. It was a more mature game. With TLJ, up until well into development, I had no idea what the ending was going to be. It emerged as I played the game myself. While with Dreamfall, we made diagrams that described the themes, and how each person related to the themes – it was a whole different process.

I think for some strange and crazy reason, TLJ has become such a treasured memory for a lot of people – the game has really affected people. And I think it is what it is, and for me to step on that would be wrong of me. With Dreamfall it’s sort of the opposite. I had a very clear statement that I wanted to make, and I followed that through. I think TLJ reflects the mind of a 25 year old, and Dreamfall is that of a 30-something. When you’re in your 20s, you don’t know where you’re heading, much like April. While in your 30s, maybe it is more about the loss of faith in yourself, faith in religion and faith in the world.

RPS: For years I’ve been trying to write this book for teenagers. I’ve got three chapters into it so many times, but never got any further. Replaying TLJ, I was so embarrassed by how much I’d stolen – totally unconsciously – and I was freaked out by it. These ideas had seeped into me. One thing I’d stolen was the notion of Balance, which is ridiculous and I can’t take. But another thing, and you can’t stop me stealing this, is the extraordinary idea of the central character not being very important. That’s almost unheard of.

Ragnar: That’s something that happened later. In the beginning it was, yes, she’s the chosen one. But then that changed, that was an extremely important part of it. And that’s why it carries over into Dreamfall. April has to be disillusioned. If not then what the hell? She went through all that, and what are you in the end? I think it’s about realising that you’re – well – a part of the [he adopts a sarcastic voice] “great wheel of time”. You’re only a cog, but… you can make a big difference.

RPS: It sounds silly when you put it like that, but that’s a really honest statement about reality.

Ragnar: Yeah. And people hated it. Both in-house and players. They felt cheated. People do expect, after playing the game for 30 hours, of course they’re going to end up being the most important piece in the whole puzzle. But you’re right, that’s also something we’re doing with The Secret World too. In an MMO, every player cannot be the chosen one. I hate that in WoW, when I’m referred to as “the chosen one”, and I’m thinking, “Fuck you! I’m not the chosen one! There’s 200,000 people before me who are also the chosen one! I don’t want to be chosen, I just want to be a person who plays a part. Why not go that route too? For me it can be just as enjoyable to be that person in the crowd, with an interesting story to tell, rather than being the King.

I have to admit, that’s not an idea that comes from The Longest Journey. It comes from many stories before. I stole from a lot of people. Neil Gaiman, Joss Whedon with Buffy the Vampire Slayer – I was watching that when I was making the game.

RPS: That shows. In a good way. People can copy Whedon really badly, and it misses on every level.

Ragnar: If you can’t do it, don’t even try.

RPS: But you succeeded.

Ragnar: I think I have a good ear for dialogue, and he had my style without me evening knowing it. When I saw Buffy I had a revelation: “Holy crap! This is exactly what I want to do.” So it’s a Neil Gaiman type story mixed with Joss Whedon style dialogue. But I have no shame about that. I think every writer should steal liberally, so long as you add your own stuff, and do it honestly. I think Dreamfall had a different identity – it was more me.

At this point we’re joined by Dag Scheve, Ragnar’s writing partner.

RPS: Having played TLJ a couple of months ago it’s interesting to see how I’ve changed. Some things that were normal gaming conventions of the time seem a bit daft now. And I’ve obviously changed a lot since I first played it. I still connected with the story very much, but I didn’t feel that same attachment. I’m 30 now, and I didn’t feel the same connection with an 18 year-old.

Ragnar: I don’t think I could ever make that game again. I haven’t played it in a very long time. I think I’d have trouble playing it as a lot is very naïve. Dreamfall is a much more mature game.

Dag: I found it a little naïve too. Although it is a good game, it’s a good story.

Ragnar: Yeah, you’re brilliant too!

Dag: But I don’t think it’s as good as the story that we made for Dreamfall. It’s not as profound.

Ragnar: No, it’s not as profound, but it has a simple joy that’s lacking in Dreamfall. It has a sense of exploration and adventure that’s lacking in Dreamfall, because Dreamfall is a lot more serious, and everybody’s questioning themselves, and everybody’s having a crisis of faith.

RPS: It’s more Buffy season 7 than Buffy season 1.

Ragnar: Yes. That’s a perfect comparison. And I loved season 7 of Buffy.

Dag: I don’t like Buffy.

Ragnar: You know, you’re not brilliant. You suck.

RPS: Have you heard about Joss Whedon’s new project?

Ragnar: Yes. Actually, I was so happy that day. It was my happiest day.

Dag: What are they doing now?

RPS: It’s called Dollhouse.

Dag: Is he doing a new adolescent show?

Ragnar: No, he’s starting in the 30s this time.

Dag: Because I like Angel more than I like Buffy.

We then get a long way off track, before finally clawing our way back to the subject, and back to character development

Ragnar: Character development is narrative. That’s a thing I learned in TLJ, and carried over to Dreamfall. I used to have a completely different opinion. I thought that story could be a good story regardless of characters. That the mechanics of a story were independent of characters. I think it’s possible – it’s doable – but I’ve changed completely. My philosophy now is that the character builds the narrative. It’s something we’re transforming fully into The Secret World, because there character development is the gameplay. But it’s also the story. It’s how you transform yourself within the game. It’s character development as narrative. Which is how you tell stories through RPGs and MMOs. That’s what you’re talking about with life being a narrative. See, so I did it before you!

RPS: I think narrative is almost a better word than story, because narrative implies progression, and games require that.

Ragnar: Yeah, exactly. What is narrative, what is story, and what is plot? I really don’t know the answer. Every story has a narrative, or does it? I’m not sure.

RPS: A character I loved in TLJ was Burns Flipper, the acerbic guy in the hovering wheelchair thing.

Ragnar: When he dies, that’s my least favourite moment in TLJ. When April comes to find him dead and she says, “You never got to walk again, did you?” [There is much laughter from everyone] Horrible! Horrible!

RPS: Despite that, he’s a great character.

Ragnar: That’s another interesting thing. A great thing with Dreamfall, and much more in TLJ, is the freedom the actors have. Being able to go off script. Andrew Donnelly who voiced him is a stand up comedian. I told him, go wild with this. The way I did the casting was to write sample dialogue for all the characters, and then I cast it. I only had the sample dialogue. Most of the dialogue for TLJ was written in a frenzy during the night. I stayed for two or three weeks in New York, and I did the writing at night until 3 or 4 in the morning. Then I went to bed, then printed it out on the crappy printer I bought, and then I’d hand them the new script pages. So the game was there, but it lacked all the dialogue. Therefore it was also very open to being able to go off script. I also knew what their voices were like. So for example with Crow, my favourite character, I think only five lines of dialogue had been written when I cast the guy. He [Roger Raines] was brilliant, just what I wanted, and the way he read it shaped how Crow’s dialogue was written. So it was written for him. And the same with Burns Flipper. It was written for that guy. Some of the outtakes are the best ones there – things I had to cut unfortunately.

RPS: I don’t want to talk about the swearing in the game, because it’s an incredibly tedious subject. But he was a good example of why it was a good idea to have swearing.

Ragnar: He was a good example of why it was a good thing I didn’t have someone standing over my shoulder while we made the game. You know, we had penises on display. I’m all for full-frontal male nudity.

RPS: That’s the opening quote right there.

Dag: That’s what I have to live with.

Ragnar: TLJ began with the penis, and we tried to do the same in Dreamfall but the publishers said, “No, you can’t do it. It won’t get released in the US.” I was thinking about sneaking it in, but I’m a more responsible person now.

RPS: I remember the original review in PC Gamer, and all it went on about was the penis and the swearing. I was so cross. So I began my campaign to mention it every month.

Ragnar: And you did. I was reading PC Gamer back then, and I think you mentioned it every single month for a year and a half. I was always searching… oh, John Walker, alright, ah yeah, there’s The Longest Journey. I thought, woo!

RPS: It became really funny to get in a mention, no matter how irrelevant. But I really take some credit for that game getting attention.

Ragnar: And you should, definitely. I think we’ve had some champions. You’re one of them, and we had some champions in the US as well. And the game sold quite well, even though we haven’t made that much money from it. It sells better than Dreamfall at this point. But both games are still selling continuously.

RPS: For me, the games have been primarily about imagination. And the importance of imagination. I think TLJ hit me at the right moment. It made a real impact. It seemed to be a celebration of imagination. One of the big messages that I got from it was, if you let your imagination die, you are essentially spiritually dead.

Ragnar: Yes, exactly. And that’s represented in the games. A friend of mine interviewed me last year and made a similar point. He said that TLJ was a game about storytelling, and Dreamfall is a game about storytelling too. You have the Storytime realm. So they are stories about stories – meta-stories. Stories about other people telling stories. And stories about the power of the imagination. Arcadia is a place of imagination, where those things are made real. It’s the kind of thing you have to think about. I’m not sure whether it was intentional or not. But I think that’s the legacy of reading a lot of Neil Gaiman, because his stories area always about imagination, and the power of storytelling.

That’s definitely the case with Dreamfall, because the structure was a story within a story within a story. It has so many starts, and they’re all inside each other. That was all intentional, especially how it wraps up in the Storytime, and how Zoe is asked to tell a story. Is that story the game? Is that her view of the story? That’s going to be evident towards the end of the whole TLJ saga – the importance of stories. TLJ starts with an old woman…

RPS: An old mysterious woman…

Ragnar: An old mysterious woman being asked to tell a story, and it ends with the same woman telling that story. That is the framework. Imagination, yes. But more importantly storytelling as a tool for imagination.

In part three we discuss why it’s so important to Ragnar to write female characters, then go headfirst into Dreamfall’s story, including a fascinating explanation of the role of faith in both games. And finally, if it will all fit in one place, the potential for Dreamfall Chapters.