Why the System Shock remake's guns are designed to be like "campy, movie props”

Lead art director Evelyn Mansell says in a game you want a gun "that does weird things.”

It’s been about an hour since Evelyn Mansell - one of the lead art directors on the System Shock remake - and I started talking about guns. Specifically the big, daft chunky guns that she worked on, but also about videogame guns in general - what makes them tick. What separates a good one from a bad one. Whether or not Doom 3’s shotgun is one of the good ones (it is).

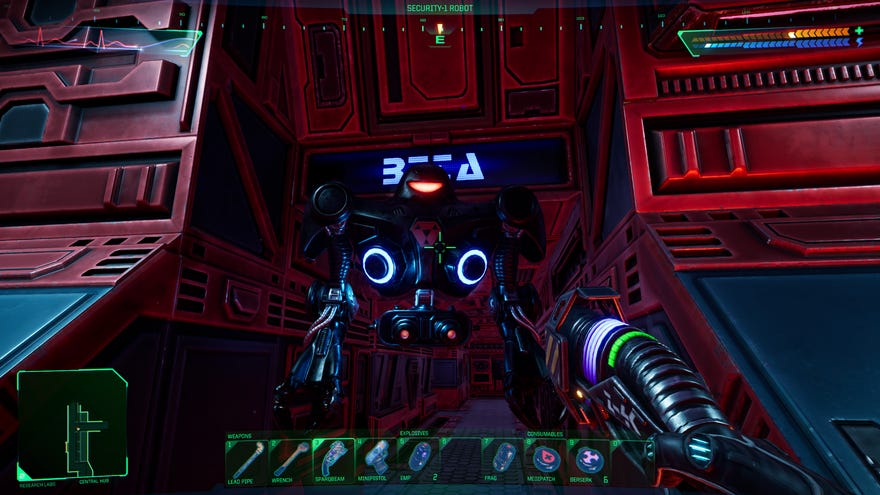

If there’s one area where all of the remake’s ideas truly come together and shine, it’s in the weapons. There wasn’t much to see in the original - nothing beyond the tip of a barrel. Here, the weapons are very much the star of the show. Heavy, industrial things covered in thumb-print smeared LCD screens and superfluous greeblies. NERF guns that've been painted by a 12-year-old and covered in spaceship parts. These are the toy guns you would have wanted for Christmas, and I wanted to know more about them.

A game filled with as much tech and grimy atmosphere as the System Shock remake is a dream come true if you’re the sort of person who is really into practical, industrial sci-fi design. Mansell joined the project early on as a character rigger, from a background in modding, before ending up becoming integral in developing the game’s entire aesthetic after a shift in development saw Nightdive Studios’ pivot from the more grounded look of the pre-alpha build to something more stylised. “I really wanted to avoid that typical Unreal Engine Remake look of shiny metal surfaces and realistic materials,” she tells me. She focused more on evoking the key aspects of the original’s style - blocky, tiled walls and high-contrast patterns. Mansell goes into more detail, telling me that she encouraged the other artists to use unconventional values for materials: “I wanted the materials to look and feel realistic but to not be the materials you would use to build an actual space station. The idea was to make it look like a miniature, like something built for a movie.”

That idea of everything being cardboard that’s been painted to look like metal is something that extends to every aspect of the game’s visual design. Everything has an exaggerated physicality that makes System Shock’s tech feel more like a movie prop or a replica. Mansell tells me that she really wanted to bring the work of concept artist Robb Walters - someone who worked on the original game as well as on the BioShock games - to life. “All of Robb’s designs would make excellent toys. That really fed into the new aesthetic. There’s all this grunge as if everything has been covered in artificial weathering and oil washes,” she says.

.jpg?width=690&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp)

It’s a concept that’s been executed perfectly, adding an almost camp quality to the weapons and environments without detracting anything from the original’s game’s atmosphere. Mansell explains that “there is a realism to the levels and the weapons, but it’s more like playing with a toy or a board game”. It ends up making the entire world feel a lot more like an actual physical space than more traditionally realistic approaches usually manage. The team mostly trusted in the player’s willing suspension of disbelief to do a lot of the leg work. Mansell feels that “it can actually be harder to accomplish that with realism - anything that falls short of that level of naturalistic perfection sticks out like a sore thumb. A consistent art style sticks with people much longer.”

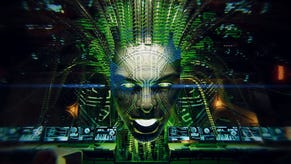

Taking such a big creative swing with a game with this many expectations and dogmatic fans must have been a daunting prospect. I ask Mansell how you even set about trying to do something new with something old. “So, at this point I really just have to admit that I’d never actually played through the entirety of the original game,” says Mansell, though she points out that System Shock’s ideas trickled down into so many games over the years that you can see them almost anywhere. They set out to recreate the game as people remembered it, not updating it exactly as it was. “When people who played the original game play it, I want them to go, ‘Oh, this is exactly like I remember’, even though it’s not literally the same,” she says, describing the process as “a tricky balance”. “There was so much back and forth on what kinds of modernisation would feel appropriate and which kinds of modernisation would detract from the spirit of the original.”

The art design of the remake has an almost contemporary indie game sensibility to it, tapping into the current trend of trying to make new games look like they were made a long time ago. Mansell tells me there was a lot of inspiration from the current 3D pixel art movement, a style that “takes those PS1/PS2 technical restrictions and then works on top of that with modern techniques”. She tells me that she enjoys working with limitations and that “having them really helped us evoke the time period that the game belongs in”.

Speaking of time periods, I have to ask about all of the gloriously antiquated technology that’s littered throughout the station. Messages are stored on USB sticks. Readouts are shown on CRT monitors. There aren’t any touch-screens in sight, everything is interacted with via big chunky buttons and heavy leavers. “There was definitely a conscious decision to tap into the design of the kinds of science-fiction that inspired the original, like Alien or Silent Running,” Mansell explains. It definitely comes through in the game itself - everything is very industrial and lived in.

All of the physical, grimy tech helps sell the station as an active work-place. There’s been an obvious effort to avoid “sleek, clean sci-fi”, as Mansell puts it. “It’s the difference between an oil rig and corporate offices.” If you’ve ever worked in an industrial setting, you’ll understand what Mansell means when she says that “when you want something to be actually usable and dependable - something that can actually be fixed if it goes wrong - you use heavy, physical equipment, not touch-screens and voice commands.”

Its in the weapons where you can see these ideas come together. Mansell tells me that they’re all “real labours of love, iterated on throughout the whole process by the whole team”. Starting with the initial concepts from Robb Waters, a lot of work went into deciding how the guns should function. “We really wanted to give the feeling of campy, movie props,” she explains. “A lot of the guns are, at their core, the bones of real guns with a plastic facade glued over them.” I can’t help but think about the way they made the blasters for Star Wars, as Mansell tells me how much of it was a matter of “getting references from real guns, modifying parts of them and then building the prop gun over the top of it.”

“We really wanted to give the feeling of campy, movie props”

It’s fascinating to hear just how much is involved in making a shooty thing for a videogame. It makes sense that so much thought should go into them, considering that they are, ultimately, the real main characters of any first-person shooter. Mansell feels that “the biggest part of getting these guns to feel like they’re part of the world is having them appear to function in a believable way”. She tells me that “as long as it looks like it’s doing something - I don’t even need to actually know what it’s doing, as long as it feels important.”

We talk for a long time about video game guns. It’s a subject that, being a medium where physical violence is de rigueur for most interactions, has had decades of thought and experimentation put into it. How do you determine a good videogame gun from a bad one? This is when Mansell tells me that she thinks real-life guns are “generally really boring, just artless tools made to kill people, engineered with only one consideration - make thing go fast, person dead.” Real guns aren’t interested in aesthetics and world-building, so I ask what sets videogame guns apart, and Mansell explains that “in a videogame, you want a gun that’s interesting - that does weird things.”

System Shock has no shortage of guns that do weird things, whether it’s throwing balls of plasma around or spewing electricity in hazardous arcs. Mansell tells me that she spends a great deal of time “thinking about Unreal’s Flak Cannon, which throws out superheated pieces of metal that bounce off the wall”. She already finds this mechanically and visually satisfying, but it also shoots a big grenade that bursts into pieces of metal, which she feels “makes some sort of sense - the gun has a sense of physicality to it. It makes me think about how to use it, the gameplay implications it offers.”

The mechanics are one thing, but System Shock’s weapons also perfectly fit the setting and help imbue it with character. As Mansell puts it, “the other aspect is aesthetics - how does it feel?” She explains that she has some of her projectiles accelerate after they leave the barrel, an effect which is “barely noticeable but it adds to that THUMP as they impact the walls”.

Despite their apparent simplicity, good videogame guns are the result of all of the collaborative work between various artists, sound designers, engineers and designers. Mansell feels that “all these little effects and touches all pour into making these things great. I think ultimately what makes a great videogame gun is the effort and imagination the people making them bring to it.”

“And whether or not it has cool little vents on the side?” I ask.

“And whether or not it has cool vents on the side, yeah.”