Wot I Think: Democracy 3

Tactical voting

Democracy 3 made Alec into Nick Clegg and Adam into an Orwellian nightmare, but their terms are over. Now Graham has been elected to tell you Wot He Thinks about Positech's political policy simulator.

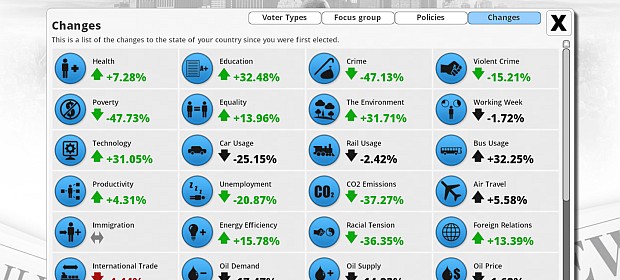

Democracy 3 is a game about a user interface. Look at this thing.

Look at those bar charts. Look at all those big, round buttons. I've played a lot of games with cluttered interfaces, but this whole game is nothing but obscure iconography. Are you intimidated? Don't be. Watch what happens when I mouse over something.

There was a flowchart under here the whole time. Democracy 3 is a game about a big menu that's an undercover flowchart.

You use that big menu to shape your chosen country, selecting whether you want to rule as the Socialist party be a lilly-livered, sweater-wearing, egghead liberal, or whether to get into bed with big business and let their oil-slick fingers frack your precious lands. The game's surface level allure lies in the way it promises to let you live out your political ideals, to see them either turn you into a beloved leader or a pariah, and see the UK, France, Germany, USA, Canada or Australia, flourish or crumble under your decision making.

The seductive power of that promise makes it easy to overlook the ways in which the game is limited.

As linked above, both Adam and Alec had different experiences, but my very first rule as leader of Britain ended in unchallenged triumph. I put alcohol tax to 50% and changed the drinking age to 21. Then I put the maximum amount of money possible into the intelligence services, and installed CCTV cameras on every street corner. I ended the sales tax, increased income tax to 50%, and set corporation tax to around 25%.

Then, I poured the extra money I was gathering into science funding, laptops for every school student, food stamps, free school meals, subsidised buses and trains, grants to help new businesses, state housing, child benefit, rent controls and unemployment benefits. Each of these stimulated the economy and, in turn, earned me more money.

Within four years of being in power, crime was eradicated and Britain was an environmental paradise. Within eight, illness fell to insignificant levels, our country was given the Kyoto award, and the science funding had given us a technological advantage that helped to eradicate poverty. I had a 91% approval rating, and eventually won a third term with 74% of the vote against an opponent who managed just 8%.

With a little patience, it's not hard to become beloved (and in the game), and to lead your nation as a single party state. It's even relatively straightforward to do so while living by (most of) your principles; by the time I was in my fourth term, I could do whatever I wanted, because I was so popular that there was little risk of me being deposed. I built a space station.

Democracy 3 is not about challenge, then. This was true in Democracy 2, as well, but there are ways to game its algorithm, exploit its odd balance, and "win". At this point, the game fizzles out; there are no new decisions for you to make and you hit the term limit as a hero.

When you reach this stage, its easy to start pointing fingers. There's a vast web of numbers beneath Democracy's surface, representing your policies, the strength you're willing to enforce them, and the population's opinions of your actions. But there's very little real politics. You never have to cope with anything as messy as a parliament or congress of fellow politicians working against your initiatives. You never have to call in favours or live by campaign promises. The same decisions present themselves over and over - do you want to allow software patents, do you want to extradite this criminal, do you believe this or do you believe that.

First of all, politicians shouldn't point. Second, Democracy might better be thought of as a game about social engineering. You're playing with a population, not via a political system, but through that big, beautiful menu.

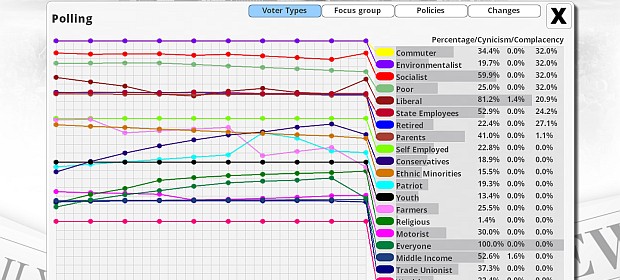

Hover over any one of the icons on its main screen and the game shows you how each issues and policy connects with those that surround it, green, red and black lines each moving at different speeds to signify the strength of influence.

Poor people? The flowchart tells me they're unhappy about unemployment and the alcohol tax, but they love the food stamps, the state housing, and the good state schools.

Hover over those state schools and I can see instantly that they are helping reduce poverty and unemployment. What happens if I lower the funding to those state schools and introduce national service? Let's find out.

I click a couple of buttons and tweak a couple of sliders, and the flowchart dribbles in a different direction. New icons appear on the main screen. Some of them are probably red, signifying that I've done a bad thing.

Whatever decisions I make, the balance feels a little off. People really love food stamps, but they don't care much at all about my turning the country into a police state. There's no simulated Twitter demographic filled with feckless bleating.

Yet this doesn't change my enjoyment of pulling on that web's strings. It doesn't need to be challenging, or realistic. It's a cause-and-effect toy.

Free from the burden of reality or of needing to win, Democracy still makes you curious. What if I abolish all taxes? What if cancel all welfare policies? What if I close the state schools? It's not balanced or deep enough to provide any pretense of what would really happen - that's the promise it can't deliver on - but approached frivolously, there's lots of satisfaction to be found in pulling its levers out of childish curiosity.

That's why I'm in love with that interface, which makes such a vast array of numbers immediately readable and playfully manipulable. It's the reason why even when you see through the facade of its theme, it's still fun to keep playing.

I play a lot of 4X games, grand strategy games, games that are jobs, games with numbers stuffed in every corner. The numbers are an abstraction of whatever fantasy the game is trying to sell - football management, middle ages lord simulation. The interface, too, is an abstraction of what you as the player are trying to control.

So Civilization 5 is a game about conquering a world. It simulates that world as a complicated array of numbers, and relates those numbers to the player via a beautiful map. Players then take actions upon those numbers by, for the most part, clicking on buttons that float above the map, like that wonderful, economical 'next decision' button Civ V placed in the bottom right of its every screen.

That game's map is great, but you don't spend a lot of time looking at it. You spend a lot of time looking at the menus. A lot of games are like this, or used to be. It's why HUDs have become more minimal, to stop you from having to play a first-person shooter by staring at the mini-map rather than the game.

Democracy 3's triumph of design is that the menu is the way the information is communicated, the way in which you dive in to interact with that information, and the beautiful thing you look at. I like that because of the economy of it. It's elegant in a way I admire separate from its impact.

But it's also why your control over this cause-and-effect system is so compelling in spite of the simulation's limitations.

It would have been so easy to obfuscate the logic behind the game's responses to your actions with a bad interface, and doing so would have completely undermined the fun of just seeing what happens when you change something. What I'm arguing for here is that the political theme, while a neat narrative hook, doesn't necessarily matter. There's fun just in tipping a domino over and watching the ripple effect that follows. Democracy 3's menu is great because it makes those ripples so easy to create and easy to follow.

If you want to play a deep, balanced politics simulator, and prove your ideals correct, then Democracy probably won't satisfy past a couple of hours of play.

But if you want to teach someone about the basic connections that form society, Democracy 3 is the perfect way to do it. Let them tinker with its infographic, and they'll come away smarter for it.

Or if you want to just have some fun, then set aside expectations of real governance, or your need to be liked, and instead be bold. Explore those what-ifs. Twist those nozzles, watch what pops up, and clap like a happy baby.

Democracy 3 is available to buy for £20 direct from its developer. It's also on Steam.