Our PC Games of the Year 2018

It'll take you all of 2019 to play them

The doors have been opened, the games inside have been devoured, and now it's time to recycle the cardboard. Below you'll find all of our favourite games from 2018, gathered together in a single post for easy reading.

If you're not yet familiar, each December we pick our 24 favourite games from the previous year and cram them behind 24 different doors. Those doors are then opened, one a day, revealing the game inside like a delectable surprise. Any game released in 2018 is valid for inclusion, whether it was released as early access or left early access during that period. Any game from a previous year is also valid if it feels of 2018 in a particular way, whether due to a substantial update, re-release or anything else. The point is to celebrate the games we loved this year, not to quibble over such trifles as time.

The list isn't in any particular order, except for the one at the end which is factually, objectively, 100% the best game of 2018.

You can still read the calendar in its original calendar form, but otherwise hit the buttoms below to start paging through enough great games that it'd take you all of 2019 to play them all.

Subnautica

Brendan: Subnautica is a game of wondrous dread. It surfaced from the slimey seas of early access in January, so it qualifies as a 2018 game, and if any of you want to argue about that, I will feed you to the deep. I like this fishy survive ‘em up because it puts humanity in its place. You’re stranded on an ocean planet, one of untold humans who have conquered the stars, but forgotten the sea.

Most survival games are about overcoming nature, dominating it, bending it to your human will. You affect the environment. In Subnautica, it feels the other way around. You’re not top of the food chain in this water world, not even close. And you quickly learn that the best way to live here is to accept that nature is king. To thrive, you have to work within it, not against it. The best way to get teeth from those Stalkers isn’t to kill them, but to play fetch with them using scrap metal. The most useful thing you can do when a terrifying new seabeast emerges from the shadows isn’t to blast it to bits, but whip out a scanner and learn what the hell it is. It’s still about exploiting natural resources, sure, but it does this in its own gentle, thoughtful way. It helps that it doesn’t offer any worthwhile weapons, and maybe it’s a sad condemnation of humanity that in order to learn humility within the natural world we must be entirely disarmed, but the result is the same: a survival game that’s about knowing nature, not beating it.

Matt: My interest in survival games tends to perish pretty quickly. There’s satisfaction in overcoming a world that doesn’t want you in it, but I was loath to start trudging on another treadmill of mundane tasks. Then Subnautica came along, and plunged that treadmill into an alien ocean.

It’s a place of terror and wonder. More the former at first, when you can’t be sure if every iridescent fish is going to be your dinner or if you’re going to be its. Gradually, though, you get comfy. You carve out a base amongst the coral. You craft some flippers. A handheld jet. A submarine.

As the world yields to your knowledge and machines, new areas open up. Dangerous areas, where oversized shadows let out oversized wails. Dread deepens with every step into the dark, a drone that batters against need and curiosity. Those caves are rich in minerals and mystery, your existence sustained by both.

Fear gives way to understanding. You set up an outpost in the depths, a metallic invasion supplied with oxygen from dead fish. You build a scanner room, turning painstaking searches into simple collections. Your work is well rewarded.

‘Rewarding’ sums up so much of Subnautica. Every project has its bounty, every zone has its surprises. There’s a unique, primal horror to being in an environment you’re not equipped for, with creatures that very much are. Subnautica’s brilliance lies in subliming that fragility into mastery.

That ocean will never be your planet, but it can become your home.

John: I’m so pleased I was dumb enough to ignore Pip’s plaintive pleas that we all play Subnautica during its early access. Because I got to experience my favourite ever survival game only after it was complete.

I’d certainly have had such a splendid time, over a much longer time, if I’d played its earlier iterations when a person with far more sense than me was imploring me to do so. But I’d also not have had the completeness of it, the beginning, middle and end of a genre that so often only offers the middle.

Despite putting in as many hours as I could, despite not mainlining its storyline at all, I found Subnautica to be a narrative experience in a way survival games almost never are. Not just because it has the whole plot to discover (and discover it you must, don’t let anyone tell you about it), but because it let me tell myself so many more personal stories as I went. Struggles to survive calamities, that first time I discovered a new spectacular species, building my home and making it feel safe, venturing into the deepest caves to find the strangest secrets...

Subnautica is as deep as its own oceans, with so much to find, so many ways to happily potter, and always with just enough sense of threat that the safe parts feel wonderfully safe. If you don’t care for survival games, don’t write off Subnautica with them - it’s something uniquely special, where the mechanics of the genre feel vital for the greater purposes of exploration and understanding.

Chuchel

John: Chuchel does something very, very few games have ever tried to do. Vignettes. While there has of course long been the madcap 5-second game modes of WarioWare and its various copies, Chuchel is something very different - something like mini-episodes of a cartoon, except as an outrageously cute puzzle game.

Each of the dozens of little scenes sees Chuchel, an ill-tempered and hungry ball of black fuzz, trying to get hold of a delicious cherry. Only to be thwarted by a red bug-like creature, the Jerry to Chuchel’s Tom. Or indeed a deific hairy hand that descends from the sky and just plucks the cherry away, ending a sequence with perhaps a nod to the animation of Terry Gilliam.

This is Amanita, they of Machinarium and Botanicula, but in a far more silly and joyful mode. Where their games are usually whimsical and musing, this is anarchic and daft, a cacophony of happy noise and colour. And most of all, goodness me, it’s so, so funny.

Playing Chuchel has been one of the absolute highlights of 2018 for me, not just because it’s a self-contained creation of joy and fun, nor just because it features exquisite animation and puzzle design, but because it was the very first time I’ve been able to properly play a game with my boy. 3 at the time, this was a game that let him make suggestions of what to do for me to try, in a way he instantly got. And even more than that, it was a game that had us both guffawing, sharing laughs in a way that really doesn’t happen often when there’s a 38 year age gap. It’s such a pure thing, pleasurable and ridiculous and with that slight edge of malevolence that makes all the best cartoons fun.

Dave: If there’s one lesson to take away from Chuchel, it’s that a lot of hassle would be avoided if people shared more. Chuchel, a black doodle with an orange hat, is fighting with a rodent-like scribble over who gets to eat a single cherry, but their dispute frequently means they lose it entirely to some other creature. They team up together to try and get it, only to stab each other in the back with the rodent-scribble usually coming out on top.

It’s very minimalist, each scene containing all the puzzle pieces needed to progress. The frantic art style and madness of what’s on display is strangely charming and by the end I was rooting for the black scribble to eat the cherry. But the thing that made Chuchel stand out to me was that it managed to tell a relatively endearing tale without uttering a single word. Characters talk gibberish, yet their gestures clearly show exactly what they desire and how they react to each other. It’s also one of the few games that nails slapstick humour, which is quite the feat. Very enjoyable for the short amount of time it takes to finish it.

Monster Hunter: World

Dave: Monster Hunter: World is probably the game I’ve sunk the most hours into this year (a whopping 81 so far, if my Steam account can be believed). I’ve slain or captured countless monsters in my pursuit to make some powerful weapons and effective armour to hunt bigger beasts.

It is utterly gorgeous to look at, with each of the five areas you can hunt in being a large labyrinth that you must memorise the optimal paths for. The vibrant locations you explore are filled with life, be it plants to harvest to craft items to make hunting easier, or the fauna that occasionally try to attack you, distracting you from the hunt.

But the main attractions are the massive beasts found with every mission. From your first hunt with the Great Jagras, all the way up to taking on the Elder Dragons, the hunts will test your combat skills in unique ways. It takes a big investment of time and effort, since you’ll regularly grind the same monster repeatedly for resources to make new weapons and armour, but chasing monsters with friends was probably the most fun I had this year, especially when you’re all working together to take down a massive Elder Dragon that’s been giving you hassle. Are Kushala Daora’s tornadoes in the final phase too much to handle? Have some friends place explosive barrels while it’s asleep so that you can end the fight quickly.

I’ve always wanted to get into the Monster Hunter series, and while I’ve been reliably informed that Monster Hunter: World is a far more streamlined experience than some of the other versions of the game, it felt suitably complex enough for my tastes. But really it did shine the most when I got a group of friends together to take down tough monsters, even though it is entirely possible to get through the main game on your own.

Monster Hunter: World also has a ton of character, which is a thing that seasoned Monster Hunter players are all too familiar with. Palicoes can be outfitted with all sorts of cute costumes, including the most recent update allowing players to turn them into little snowmen. You can also create more personalised armour that either upgrades your character’s abilities, or gives them slots to put decorations in to customise them to your liking. There’s even a woolly pig in the main hub area, for no other reason than to be cute.

It was most certainly worth the wait for it to come to PC, even if it didn’t have the best of starts. Now that the updates are coming thick and fast, we’ll hopefully see some more returning monsters from the prior games in the series, as well as new beasts to slay.

Matthew: I’ve not progressed much in Monster Hunter World, the popular videogame adaptation of Rock Paper Shotgun’s extensive tips guide, but that’s entirely because I’m hooked on walloping the game’s first monster, the Great Jagras. It’s far from the most spectacular beast in the game -- it’s basically An Iguana But Big -- but it has one of the most satisfying takedowns I’ve seen in 2018.

The Jagras likes to gobble up smaller creatures to heal and strengthen itself, distending its belly with the unfortunate Aptonoth it swallows in the opening area. (Incidentally, one of the best bits about this fight is how it plays out like clockwork, so you can always enjoy Jagras-whuppings on tap.) As a fellow overeater I see a lot of myself in its sad, post-lunch waddle, but as a monster hunter I only see an opportunity.

Hit its fat tummy enough and the beast vomits up its meal, leaving it as a wheezing heap on the floor and ripe for further bashing/stabbing/whatever-the-hunting-horn-does. Yes, it’s unkind to pick on anything in that window of post-puke vulnerability (see also: Hitman), but I love the logic of this particular tactic. It’s such a reliable technique that it’s especially good for feeling the improvements of your weapon upgrades; every sharper blade I build I’m right back there, smashing its stomach to see how much faster it delivers street pizza. If that’s not worth a recommendation, what is?

(My compliments to The Vomit Thesaurus for the phrase ‘delivering street pizza'.)

Alice Bee: Dave totally grokked my Palico love. Like, the best thing about MonHun: World is obviously the fashion. Yeah, living eco-systems and whatever, but good lord, the outfits. The armour sets range in style from puffy winter wear to bondage night in Shoreditch. Some of them are spectacular. And your Palico basically becomes an accessory, like a chunky handbag.

These outfits are all made from the skin, scales, armour, teeth, feathers and fur of the beasts you've successfully hunted. If you wore any of it down the street in real life you'd be covered in red paint almost instantly. And it's hilarious because all the Monster Hunter HQ lads are going on about how amazing and wonderful these rare creatures are and how we should respect them and study them, and then send you off specifically to kill them. Like, yeah, I'll study it up close, I'll study it real close, with this big mace made from the bones of its cousin.

Basically, the core of Monster Hunter: World can be summed up with a small section from that Radio 1 interview Tom Hardy did where kids sent in questions:

"We can see ourselves in all living things, so one has to care about everything and approach it with love -- unless of course it attacks you. In which case, lovingly, see it off with a big stick. Love all things buddy. Unless it's coming at ya mate. [In which case] dispatch it with the love, man."

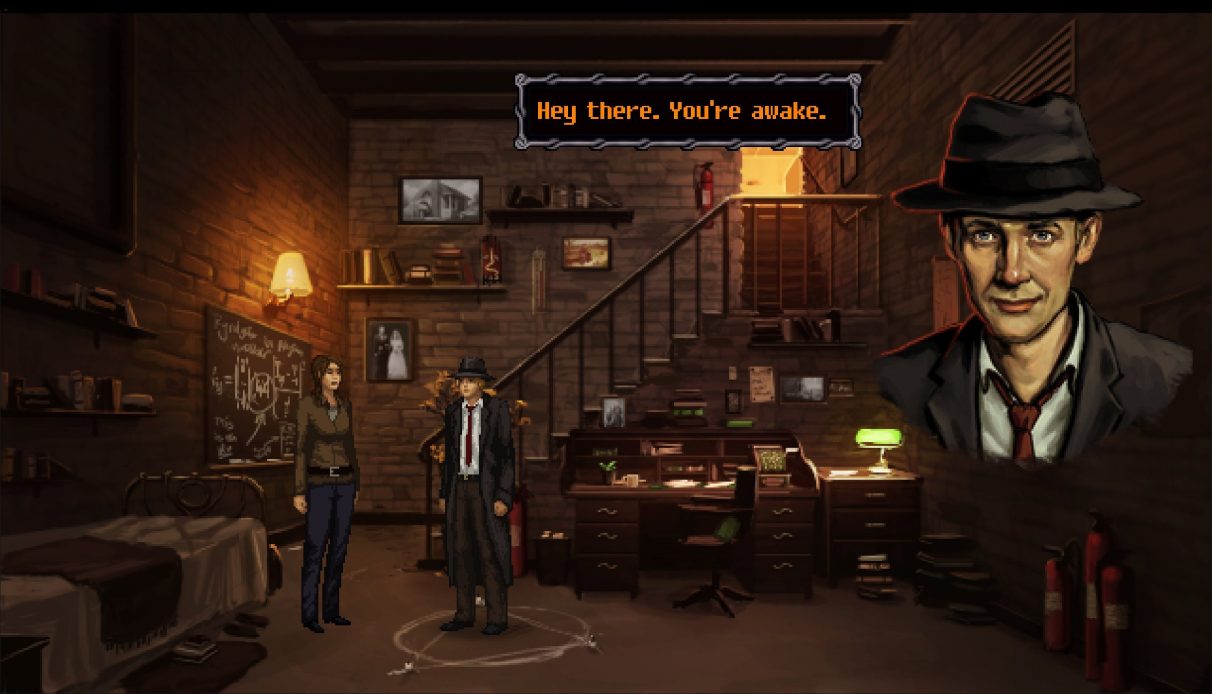

Unavowed

Alice Bee: I love point ‘n’ click adventure games, because they got to me at a formative time. One of the first games I ever played was Day of the Tentacle. Then The Curse of Monkey Island. I worked around the LucasArts/Lucasfilm stable for a bit. Adventure games will stay with me, like everything else that touched me between the ages of 10 and 16: scented gel pens; Blue WKD; crushing parental disappointment at GCSE results.

They tend to be ‘if you liked Monkey Island, then check this out!’ games, though. They come with a caveat built in from the ground up, usually even in the press releases, because they scratch a specific kind of brain itch. And often they aren’t very good, but I play them anyway, because of that itch. But Unavowed is very good. It’s the ‘if you like video games, then check this out!’ kind of game.

A band of cool misfits teaming up to solve supernatural crime is extremely my jam anyway; it’s basically every TV show I regularly watch. But Unavowed has so many twists and turns and entanglements, and the characters are so beautifully drawn, in every sense. You want to play it over and over again, not just because you can pick three different origins for your character (what’s the word? Replayability?), not just because puzzles have different solutions depending on who you’re with (the strong lady will throw a brick through a window; the police detective can shoot it out) but because of how the different members of your squad talk to one another.

Backstory and personality are revealed in the incidental party banter, but you can only take two of them with you on a mission. Different situations can trigger different conversations, so all together there a lot of possible combinations. Eli the fire mage was my favourite. He is preternaturally long-lived, and watched from afar as his children grew up and then aged past him, having faked his death to protect them. He is well-mannered in an old fashioned way, but deeply sad and conflicted. And like any of the characters, you find most of this out by walking around in the rain in New York, waiting for your team to talk to each other. And the weird thing is that you want to.

John: Every year there are one or two good adventure games. This year we had the splendid Unforeseen Incidents, a fantastic example of the form. But we also had Unavowed, that did something different. It was a fantastic example of an evolution of the form - something traditional point-and-click adventures haven't seen since the '90s.

Dave Gilbert has always shown a deft had at creating great stories and decent puzzles in a very traditional fashion, and using Adventure Game Studio meant they also looked like the classic early '90s games they were in the spirit of. But in Unavowed, by intelligently lifting key elements from RPGs, he adapted a genre that has been stuck for decades and showed what else it could be.

Of course, it could be argued that it actually all happened the other way around. That RPGs picked up where the adventure game became stale, took the best elements of the conversational choices, the impactful decisions, and put them in a whole other genre. Unavowed perhaps marks the reclaiming of this, using the ideas BioWare developed (until they forgot them), letting you choose between companions have having accordingly different experiences, having different decisions have different consequences, and even changing the puzzles you see depending upon how you play.

Whatever it might be, Unavowed shows that there is still life in the old genre yet, that there are new places for pointing and clicking to take us. And frankly, if one man can do it, then teams should be able too. I desperately hope this sees others try to follow, although I feel wearily certain in a world where adventures can only ever be minor indie niche hits, it's incredibly unlikely they will.

But this year it matters not, because we got the wonderful Unavowed, and for now that's lovely.

Forza Horizon 4

Matthew: At the time of writing, winter is about to arrive in the Britain of Forza Horizon 4. It will coat the open world in snow for one chilly week and then have the good manners to bugger off for another three. Playground Games have long catered to the impatient - this is a series where you can come in last and still unlock the next race - but accelerating the seasons into a monthly blur of wet mud, soggy bluebells, frozen lakes and sweating sheep feels like a whole new level of instant gratification. And I love them for it.

I can think of few games that work so hard to make my life so easy. Its campaign is a vast spread of driving disciplines, but I can totally ignore the stuff I don’t like (crunching into bollards in Edinburgh street races) to spend more times with stuff I do (shattering every bone in my ass as I throw jeeps off Arthur’s Seat in cross country). The more you play a discipline, the more you get of that discipline, which is really how all games should work out what to offer you next.

And the racing itself is built around beautiful scaling difficulty. You can tune your drive from ‘pretty much just hold accelerator and you’ll at least get to the end’ all the way up to the sim-like depths you’d expect from its grumpy big brother, Forza Motorsport. (I can’t speak to Horizon’s quality as a sim, but there are a lot of words I don’t understand on the tuning menu, which is usually a good sign.) Win too easily and Horizon politely asks if you’d like to punch up the difficulty. Asks, not demands - it’s not just the landscape that’s stupidly British.

And it’s such an incredibly good natured game, a celebration of all things wheeled. Yes, it fetishises the the playthings of billionaires, but its garage of 400+ cars is also full of quirky old bangers from Britain’s automotive glory days and the humble hatchbacks you learned to drive in. There’s also a new side story based on a YouTuber recreating classic racing games. Yes, that sounds ghastly, but to see Playground acknowledge its debt to Project Gotham Racing, Smugglers Run and OutRun is genuinely endearing.

As someone who failed their driving test nine times it takes a lot to get me to look past that psychological scarring and settle into a virtual driving seat. Forza Horizon has long aided that recovery, and this is the best one yet.

Graham: It normally takes me a good hour at least to start having fun in a game, as I bat away cutscenes, memorise controls and slog through tutorials. Recent driving games like Need For Speed and The Crew have been no different. If we were judging games on their first ten minutes however, Forza Horizon 4 would be the best game of 2018. In that short time it gives you a brief taste of four different kinds of vehicle across four seasons and four locations in its bucolic British countryside, with each time-skipping transition made via a seamless match cut.

If the game had ended there, it would have been a superb 30 Flights Of Loving successor, but I'm glad it didn't. Everything that follows is similarly slick. Forza offers you an abundance of map icons just like every other open world game, but I never felt exhausted at the prospect as I do in many of Ubisoft's equivalents. Partly that's because the story is light and silly, starring a cast of car-fetishist festival organisers carrying clipboards who think the only thing better than wheels is you. Partly that's because hurling 4x4s down mountainsides is more fun than most action-adventure fetch quests, and FH4 has variety and pacing that most open world games lack.

But mostly it's because traversal is fun when you've got hundreds of cars to choose from and can drive to your destination as the crow flies.

I don't drive in real life, which means all my experience of real cars comes from the passenger seat. Most of that experience was when I was a kid, sat in the backseat of my dad's car on long drives across Scotland. Whether driving on motorways or single-track country lanes, I'd spend that time looking out the window, imagining myself running along the fences and hilltops of the horizon, or wondering what lay beyond the dense treeline.

Forza Horizon 4 lets me recreate these days by allowing me to drive cars my family owned on similar motorways and country-lanes, but also fulfils fantasies by letting me veer off those roads and go barrelling straight through the treeline and towards that horizon. Whether driving a Peugeot or the Jaguar XJ220 I coveted as a ten-year-old, your car is a juggernaut, and stone walls, lampposts, and all but the sturdiest of trees will tumble before you as you speed in a straight line towards your next objective marker.

This is a fun, joyful, generous game. Its first ten minutes are the best of 2018, and all the minutes that follow are pretty damn close.

Yakuza 0

Alice O: The game dad is a man known for demonstrating his love for his surrogate daughter figure by stabbing men in the neck. The daughter figure will work for hours to make the game dad even crack a smile. The game dad will only voice his feelings at the bitter end. The game dad is a tedious symptom of ageing developers struggling to reconcile their love of stabbing necks with their love for their new children. There is another way.

Yakuza 0's game dad is a beefy mobster with a heart of gold, bound by his sense of honour and duty to unravel a conspiracy that's threatening to tear his crime family apart and has already seen him framed for murder. He shouts. He growls. He bodyslams thugs. He kicks teeth out. He straight-up stabs several people. He races slot cars with children and helps them to believe in themselves. He pulls shapes with Michael Jackson. He teaches a band of adult punk posers how to act tough. He gives a chicken a job at his real estate company. Oh, and our Kiryu is only one of two wonderful game dads in Yakuza 0. The other, Majima, is a wiry psycho with a heart of gold. I love my two game dads.

Sega's open-world brawler RPGs don't strike a balance between crime drama and wacky dad antics as much as lean so hard into everything that sure, I'll go along with whatever it wants. Its tone is: a lot. Yakuza is all melodrama, all the time, in every aspect. Every boss battle a monologue. Every sidequest a personal story. The game dads give everything their all. They can't even fight without breakdancing or heaving a startled man above their head, leaping into the air, and slamming him down face-first. I adore it.

I'm happy simply running around those bustling cities, pushing through crowds, eating a big dinner, singing karaoke in ridiculous costumes, going bowling, eating a second big dinner, running Majima's hostess club in maybe my favourite minigame from any game, and helping every single person I talk to. God help me, I've even tried playing Mahjong. I gave up on Mahjong.

Matthew: I don’t know about GOTY, but Yakuza 0 definitely stars my GOTY - gangster of the year. His name is Hiroki Egoshira, aka Mr Shakedown, aka The Biggest Bastard In Kamurocho (a highly contested title). He roams the streets of Sega’s party district looking to steal our hero’s hard earned cash. By which I mean, cash I punched out of another man’s face. Egoshiro will do exactly the same to you if you let him, and because his fists are the size of bollards he’s more efficient with it. Lose the fight and he’ll take every penny in your pocket. Not so bad early on; devastating when you’re trying to save 100 million yen for later upgrades.

He’s easily avoided, but when you do spot him you can see the money he’s currently carrying - an often massive sum floating above his head, beckoning you to come and take a swing for a big payday. Even better, you can find him sleeping on the pavement and siphon money from his pockets, but at the risk of waking him. Going back for repeat pickpocketing has all the tension of Pop-Up Pirate, only Pop-Up Pirate wouldn’t kick the shit out of you once he’d popped. Egoshira is the perfect blend of brisk arcade design and memorable character building.

That’s the magic of Yakuza 0 in a nutshell. It’s a world where any interaction can be turned into a hectic minigame, be it rhythmic button thumping to sing drunken karaoke or impressing schoolgirls by sniping chat-up lines in a shooting gallery. And it’s a place you can’t walk down the street without getting pulled into harebrained distractions - in the opening hours alone you’re protecting Michael Jackson, chasing a must-have JRPG through a chain of increasingly baffled muggers and teaching softies how to be punks. At the very least this has to be the funniest localisation of 2018 - no game has made me hoot louder.

In fact, seeing how much soul Sega captures with a couple of static, un-voiced dialogue boxes reminds you how poorly its done elsewhere. What a cast of fabulous freaks this is. Papillon Kato! Steven Spindig! Ayu the nervous dominatrix! The Walking Erection! This is a world of characters - and names - I adore. That I’m still to solve the central conspiracy - a surprisingly gripping tale of property corruption - speaks to the distracting power of everything else.

Yakuza 0 has no desire to be seen as a realistic life simulation, but it has more life in it than any game I’ve played this year.

Spy Party

Matthew: It’s Spy Party and I’ll cry if I want to, cry if I want to. You would cry too if it happened to you. ‘It’ in this case being shot by a sniper who is watching the aforementioned shindig from across the street. To win the game, the spy at the party has to complete a list of objectives without drawing attention to their very human behaviour in a crowd of very non-human NPCs. It’s one of those clever asymmetric multiplayer thingies, which is a fancy way of saying 'you'll likely enjoy one role more than the other and grow to resent the time you aren't playing as it’.

I'm definitely a better sniper than spy. I find parties quite hard work to relax at when there isn't a laser sight swaying on my back. But trying to act with the drive and purpose of an AI is still a delicious bit of role-playing (and something I miss now that Assassin’s Creed ditched its excellent multiplayer mode). Would an algorithm stride in a straight line to meddle with those statue heads? Should I try and fake a glitch and walk against the side of a table? There is something hilarious in making these dumb calls and watching that laser dot instantly snap to your back.

On the plus side, I like that the spy's secret code word to contact the double agent is 'banana bread’. This is because, 1) I like banana bread and enjoy being reminded of its existence, and 2) you can fake contact and say the phrase out loud to paint suspicion on another character and there is something deliciously grim about dooming a life with such a dumb phrase. You wouldn't hear it in a John le Carre novel, would you?

Spy Party is a game full of quirks like these - one of those ‘easy to pick up, difficult to master’ affairs. It's one of the few games that everyone in the RPS video department instantly took to, and I've grown fond of it as a team bonding tool (albeit one that involves more headshots than the usual trust exercises).

Play a few rounds and you'll start developing theories about which character models are more likely to catch the eye, and which parts of the room are best hidden from the sniper’s gaze. Alex's excellent mechanic column on the game talked about it in fighting game parlance, and it really does have that vibe of building a favoured strategy. Only instead of debating the value of Ken's dragon punch over Ryu's, you're pondering whether an old lady's big, purple hat is more or less incongruous than a dwarf in a tuxedo. Come on, of course this was going to be on the RPS GOTY list.

Alice L: I don't want to sound like I'm bragging but: I'm really bloody good at Spy Party. It's actually the only game I'm any good at being a hitman in, as I'm quite good at sussing out suspicious behaviour at small (virtual) parties, but less good at hunting an actual target down on a huge map without arousing suspicion. Maybe I should play Hitman how I play Spy Party? And then maybe I'd be actually good at it?

The RPS video team, AKA Team Lemons, have featured Spy Party a couple of times on the channel. One time where I went head-to-head with Noa and obviously thrashed her, and the other was during EGX, when we streamed for the first time ever. (Technically the first game we ever streamed was Human Fall Flat, but it was a weekend of first-time streams, so it counts.)

Spy Party is a great game to play with friends because being on both sides of the screen is thrilling. I do perhaps enjoy being the sniper more than the spy, but I think they both have their charm. Trying to act like AI is something I do well at in real life, walking into a room, awkwardly walking around it, and then bumping into things on my way out is a speciality of mine. So you can only imagine how good I am at it in this game, where you’re most likely to win if you act like a generated computer character. Did I mean to pick up that statue and put it down again awkwardly? Or did I actually just change it from a bird to a bust?

I’m also incredibly - but secretively - competitive, so winning a round of Spy Party feels absolutely magical - and as I said, I win often. I promise the reason I love this game isn’t just “because I’m good at it” but it is because I have had a lot of fun with this game this year. Banana bread.

Graham: We say every year that games are eligible for the advent calendar if they have been substantially updated and therefore feel 'of' that year. Spy Party qualifies. I think I first played it around seven years ago, when it was using placeholder human models and assets from The Sims. Its recent updates - the most significant of which includes six new maps - have made it newly relevant again. And if, like me, you hadn't played it much since those early years, you'll find it's now a beautiful, deep multiplayer game through and through.

Warhammer: Vermintide 2

Matt: “The Skittergate once again work-works!”

Warhammer: Vermintide 2 was my first visit to the Warhammer universe. I bloody love the place.

That’s odd, because it’s a miserable, blighted landscape plagued with rat hordes, dark magic and chaos warriors. Those rats are fantastic at naming things, though, and they’re oh so satisfying to splat.

Is this essentially Left 4 Dead with wizards? Yes. Is that an excellent idea? Also yes.

I prefer it, in fact. Vermintide 2 takes the best ideas from Valve’s horror shooter, and embeds them into a game where the hordes don’t feel like tissue paper. Most enemies are weak, but they’ll still chew you up if all you do is hold down a mouse button. You have to strafe and block, time every slash and use your class ability strategically. Every engagement is engaging.

That’s especially true against the bosses, which have made me laugh more than anything in any game this year. I’ll never forget that time a tentacled chaos-spawn slurped its way around some ruins, its position trackable by whichever friend happened to be shrieking. You think you’re the king of the world, then a half-formed sack of mouths and gore picks you up and starts to eat you.

Then your pal chucks a bomb, and you’re cast to the floor as the beast turns on a fire mage who immediately regrets their heroism.

They don’t really, though. There’s a unique gratification to saving your friends at the last moment, a camaraderie only slightly spoiled by the way my character spent the whole game insulting her fellow adventurers. They’re a snarky bunch, these witch-hunters and warriors, their personalities mostly embodied in bluster and put-downs. That’s OK. I enjoyed apologising for my elven barbs.

If that grates rather than gratifies, then that’s OK too. It’s the banterous set dressing to missions that stand strong without them, to level design that’s visually spectacular and mechanically thrilling. One mission takes place almost entirely within a cave, the very last section a desperate sprint towards the light. Others involve solving simple puzzles while fending off hordes, in one case building to the best ‘I’ve got it!’ moment I’ve ever been treated to.

I wouldn’t call Vermintide a horror game, but it can definitely be a scary one. Fear taps into reptilian circuits that plunge us into the worlds our avatars inhabit, into believing that there really is a bile troll at your back. There’s a totality to panic, an urge to act that grips where other emotions only guide.

Social panic offers a special kind of pleasure. When you’re fleeing from the same rat ogre, or on the brink of being overwhelmed by a sea of snarling rodents, that panic invokes presence in a shared situation. You all have your own roles to play, you all get your moments in the spotlight. Left 4 Dead figured out how to keep players on their toes with AI-horde directors, and the templates for special enemies that necessitate teamwork. Vermintide 2 combines those ideas with its own, resulting in the most fun I’ve had in a co-op game since Portal 2.

Also, hitting stuff feels real good.

Assassin's Creed Odyssey

Matt: I don’t think I like Assassin’s Creed Odyssey for interesting reasons. I still like it quite a lot.

I could point to the side quests, which have had me accidentally murdering the mothers of voluntarily caged idiots then not-so accidentally sleeping with their fathers. I’ve improvised children’s bedtime stories and helped decorate their sad clay model substitutes for friends, and punched Olympic champions to prove I’m good at running.

I’ve also spent a lot of time just fetching herbs, and beating up bears.

I could point to the combat, a vast advancement over the Creeds of old and an iterative improvement to last year’s Origins. There’s the kick, of course, but clamber up the rest of the skill tree and you’ll find varied abilities that suit different playstyles. The different weapons are fun, too, especially the special axe attack that lets you chain one-hit-kill over the head swings.

It does get repetitive, though. After a few dozen hours.

I could point to Kassandra, a Hellenic hero who won’t take nonsense from any malaka. She’s written well and acted better, the best assassin since Ezio. Though she isn’t actually an assassin, and will do murders for anyone who chucks her some drachmae. Character consistency is hard to come by in a game that incentivises stabbing passing guards to top up adrenaline metres.

Ultimately, I like Assassin’s Creed Odyssey for its world. Of course I do! Acres and acres of achingly beautiful coastlines, mountains and forests. It’s staggering that Ubisoft have filled so much space with so much identity, with vistas that so rarely look alike. There are nearly a hundred synchronisation points in Odyssey, and all of them deserve a visit.

Oh, and the final boss fight is wild.

Alice Bee: Despite the fact that I am well aware of its flaws, and that I know it is in many respects as shallow as a 1am puddle of wee outside a kebab shop, I cannot get enough of Assassin’s Creed Odyssey. The frequency with which you ding levels, or complete missions, and get a big gold sparkly swoosh on the screen, makes you feel like you’re achieving something, even when the amount of time you’ve spent playing the game means your real world achievement is less than 0.

It’s also a lot of fun running around Greece and seeing all the ancient places in a pre-ancient form. I was really excited going to Delphi and the Parthenon and Olympia in the game, because I have been to those places in real life on a school trip. stood next to sections of fallen pillars from the temple to Zeus in Olympia. They’re wider than a grown adult is tall. They’re amazing! And in the game I’ve seen them standing up again. (Incidentally, if you are ever in London you can go to the British Museum for free and see half of the surviving marble from the Parthenon, which one of our Lords nicked in the 1800s claiming he had permission from the Ottoman Empire, and we will not give them back. The Museum's position is that "the sculptures are part of everyone’s shared heritage and transcend cultural boundaries". This sort of thing is why England is still not very popular.)

For my analysis of Kassandra, please see this poem:

Sonnet 43 by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of being and ideal grace.

I love thee to the level of every day’s

Most quiet need, by sun and candle-light.

I love thee freely, as men strive for right.

I love thee purely, as they turn from praise.

I love thee with the passion put to use

In my old griefs, and with my childhood’s faith.

I love thee with a love I seemed to lose

With my lost saints. I love thee with the breath,

Smiles, tears, of all my life; and, if God choose,

I shall but love thee better after death.

Celeste

Graham: I first played Celeste a few years ago via the free Pico-8 release. I enjoyed it, but I confess that I was a little disappointed when TowerFall-developer Matt Thorson announced that he and a team of people were making a fuller, polished version of the same idea. The best it could be, I thought, was an exceptionally well-made version of something conceptually ordinary. The kind of game I'd enjoy playing but never be truly excited by.

I'm an idiot, obviously - and kind of a dick - because Celeste proved me wrong in two ways. The first is that it's conceptually exceptional too, thanks mainly to its idea-packed level design. That your moveset remains the same throughout - run, jump, a depletable air-dash - doesn't matter when each area you visit introduces environments which use those abilities in radically new ways. My favourite introduces floating, solid blocks that can be passed through when you dash into them, forming funnels you can enter to launch yourself into new areas if you can find the right angle of approach. That each of these areas is used to tell a story about mental health via mechanics makes it all the better.

The second way it proved me wrong is: there's no limit to how excited I can be about something this exceptionally well-made. To be clear, I always knew that making something this polished was hard, and I also always knew that it was rare. There's surprisingly few platformers that are as focused on movement as Celeste is. But across its level design, its art, its music, and the feel of the simple actions you can perform in it, Celeste is a masterclass.

Katharine: What is there left to say about Celeste? We gave it our old-school Recommended badge when it came out back in January, and by the time July rolled round we'd already pegged this most excellent platformer as one of our Bestest and Most Top PC Games of 2018 so far. In the intervening months, it's (quite rightly) won a ton of awards, both for its incredible jumping and how it tackles its themes of mental health, anxiety and depression, and it's remained there, high up on our ever-growing mountain of bestest PC games, ever since.

That's partly because Celeste's dash is so gosh-darned superb - the tightest and most satisfying of any PC platformer that's come out this year in my books - but what really elevates Celeste from all your other jumpy PC games is the way Madeline's movement is so intimately entwined with the environment and the things she's trying to escape and get away from.

It's a game about overcoming challenges, both physically in the game's design, and mentally inside Madeline's own head, each setback giving you more determination to try again and give it another go. And even if that proves too much, Celeste isn't a game that tells you to simply pull your socks up and 'cope'. Instead, its clever Assist Mode says it's all right to not be very good at jumping, and that asking for a little help sometimes is perfectly fine (take note, Dark Souls).

Ultimately, though, it's the jumping that carries Celeste up that mountain o' games, and I suspect it will be quite a while before another platformer even comes close to matching its sweet, sweet dash.

FAR: Lone Sails

Katharine: When I arrived at university in the mid 00s, phone photo filters were just starting to become a thing. The newest and most popular was one that rendered an entire picture in black and white, save for a few things highlighted in red. If your phone was really fancy, you could even choose which bits to turn red, too. A cool trick, I thought at the time, if only because my measly Nokia 3210 could barely make and receive calls and texts, let alone take actual photos. Then everyone started doing it to every photo they ever took. It got boring real fast, and I was quietly glad when it finally became uncool about two months later.

Fortunately, FAR: Lone Sails has resurrected that idea with timeless style. With its moody, grey landscapes punctuated by the bright, auburn nose of its tremendous car-boat-train contraption and the hooded coat of its tiny wanderer man, this is one of the most achingly bleak yet beautiful games I've played all year - and a heck of a strong debut from Swiss developers Okomotive, too.

The star of the game is your giant land boat, which you lovingly tend to and care for as you whisk your way across a damaged and war-torn stretch of countryside. It's a huge great thing, taking up almost half the screen when you're pumping its valves and pushing switches inside it, and its cavernous innards make you feel small and powerless as you scurry across each of its three floors in order to keep everything moving.

However, when you switch over to using its titular sails for a spell and the camera pulls back even further, you realise just how insignificant your thumb-sized speck of a human really is in this monstrous, industrial landscape. This is a world where powerful machinery rules the roost; humans are merely there to keep the lights on and hide inside.

Despite the game's cold, hard exterior, though, there is so much life to be found right on your doorstep. Your land boat is a wonderfully tactile and dynamic breed of vessel. As you strain to lock its power switch into place, carefully making sure to expel any excess steam building up that might inadvertently cause a fire, you can really feel the heft and might of this grey-red beast start whirring to life as its gears and cogs groan and splutter in the engine. It's a wondrous bit of design, aided in no small part by its clever soundtrack, and it helps to make this hulking collection of nuts and bolts feel alive and homely.

You start getting so attached to it, in fact, that every knock, graze and bump fills you with dread, like it's some kind of colossal robot toddler that has no control over its own limbs. This sense of parental responsibility is further reinforced by the fact you've got to constantly keep feeding its bright blue core with barrels of fuel or whatever bits of trash you can scavenge from outside, too, as you can only coast on its sails when the wind's strong enough. In the moment, it's not unlike the frantic plate-spinning of Lovers in a Dangerous Spacetime, but here the game's sense of urgency comes not from the constant threat of total and utter destruction, but from the need to keep this mecha-baby alive so you can see what's left of the world around you. After all, it's only you keeping it all together here, and without careful management everything - you, your ship, your journey ever eastward - will coming to a slow, grinding halt.

FAR isn't simply about poking and prodding a bunch of levers and switches, though. It's also brilliantly paced, regularly making you venture beyond the walls of your makeshift stronghold to investigate the battered and broken world around you. Sometimes it's simply to clear an obstacle blocking your path, other times it's booting up other old machines to give your boat a new lease of life - and the more meticulous among you will almost always be rewarded with signs of life from previous travellers if you take the time to look. Despite everything pointing to the contrary, there is plenty of life to be found in this forsaken desert, and you are the one who's slowly but surely rousing it from its slumber.

What lies at the end of your journey? That would be telling, but I can wholeheartedly say it is absolutely a trip worth taking. It's a game of quiet wonder with a warm and tender core, and I guarantee you'll never look at a car-boat-train the same way again.

Graham: Katharine has already wonderfully encapsulated FAR's strengths, but I wanted to add, in modern parlance, that this is the game I think the most people slept on in 2018. It's not my favourite game of the year, but the ratio of how much I like it versus how many people I see playing or talking about it is the most out of whack. And that's a real shame, because it's one of only a handful of games in this year's calendar that I'm confident anyone would get something out of. Heed what Katharine has written above and add it to your pile to catch up on over the Christmas break.

Zones

Alice O: You know when you fall asleep at 2am during the credits of an artsy 70s horror or sci-fi film where the synth soundtrack warbles over slow shots of landscapes blown out in unearthly colours with lens filters, then your dreams trap you inside a seemingly endless version of that unreal landscape and the synth warbles on and you feel curiosity and unease but not quite fear? And you walk and you walk and you run and you run and you glide and leap and the landscape very slowly reveals anomalous objects like buildings that aren't buildings and elevated highways that aren't highways and incomprehensibly large crystals and citrine shards that glide through the sky like angular goldfish and it's just you and the music and the landscape possibly forever and sometimes you move with such terrible speed that you fear you have become something terrible? Connor Sherlock's walking simulators often make me feel that.

Zones is a compilation of five stroll 'em ups Sherlock originally made for his 'Walking Simulator A Month' Patreon, collected and sold separately so non-subscribers can explore them too.

My favourite is Witch Of Agnesi, visiting a purple-tinted foggy forest. Trees, grass, rocks, hills, stone circles... you get it. But! Unlike many walk 'em ups, here we can sprint at great speed and leap over trees. The name, the movement, the music, and having recently seen films like The VVitch and Hereditary made this a strange sort of liberation, a feeling of great power but also horror. Whatever I am, I must be a terror to behold - but I'm free.

Others visit a dark mountain range where neon squiggles swirl through the air and collect in great columns like lightning blasting up into the sky, plains dotted with ruined stone buildings and crossed with vast roads which look like elevated highways but have rocky outcroppings growing through them and are definitely not highways, a barren blood-red world of glistening rock and jagged stones almost like hairs beneath aurora, and a landscape with a strange futuristic industrial(?) installation beneath a vast yellow crystal. In some we have some sort of jetpack and can boost on high, in others we're just a regular person.

These places are big. Very big. I've sprinted for many minutes in a straight line and not reached the end of any. They may be infinite. You'll see the same objects repeated, old parts in new arrangements or new places, but that's fine. The hypersaturated colours blowing out detail combined with the scale make them dream spaces which give me that feeling of being in those movie credits panning over a scale model. And the music is key to this.

Primarily retro-sounding synth with occasional tinklings of piano and bashing of drums, it's always a little alien and often melancholy, music for the experience of one person. It's a huge part of the moods I feel in these places, and of the journey. Even if I'm passing through a long barren stretch, the music creates a rich texture.

These walks are unguided. Pick a direction to head in or a distant landmark to investigate, and off you go. Cresting a hill might reveal a distant glimmer, a new goal, which you eventually discover is an irregular rockpube arcing with electricity, or a glowing stone circle, or something which triggers a change in the music, or... I don't know. I do not know the inner workings of these Zones, and I don't want to.

I've been enjoying Sherlock's work for years and it's exciting to see him still try new things. Days and nights and suns and stars and boiling clouds rolling through the sky lead to dramatic moments in parts of Zones, dawn breaking behind a skyline of neon crystal spires or darkness falling when I've somehow found myself deep down a chasm.

"It's not really a place," Twin Peaks fan-favourite character James Hurley once growled about where he rides his cool hog to, "its a feeling." The same with me and Zones.

Sometimes, at night, I find myself back in these places.

QUBE 2

Alice L: QUBE 2 is the Portal 3 we never had (yet, I'm still holding out hope for a Portal 3). It brings you mind-bending puzzles in a sci-fi environment full of different rooms filled with new challenges.

Your name is Millie Cross, you find yourself stranded on a vast, open, alien planet and the last contact you have with earth is a phone call from your husband and dog. You make your way through a sandy storm and you black out. When you wake you find yourself waking up in a building filled with cubes. Now, I know you're probably thinking this doesn't sound much like Portal, but this is only the beginning. Once Millie gets her bearings inside the building she is met by the voice of Emma Sutcliffe, who tells you to remain calm. You’re apparently suffering from cryogenic induced amnesia, she thinks you were tasked with destroying “the Cube,” (see, more cubes) and you’re in a suit that will give you the ability to manipulate your surroundings (which are specific white squares... or 2D cubes). Your task is to reach a human distress signal in this weird, blocky, stark, environment.

I dunno why I don't trust Emma, but I have a sneaky suspicion it's because of a certain Bristolian personality core from Portal 2. She helps guide you through the strange planet which means using some special gloves to get to your end goal. The gloves let you create different coloured squares - green generates a cube, orange a platform, and blue makes you bounce. Your job is to get through each progressively more difficult chamber by smashing through doors and pressing buttons, using oil, fire, magnets, fans, massive ball bearings, and your roster of different coloured cubes. It’s not a gun, and it’s not all physics based, but the same ideas behind Portal are present.

It's the restrictions on your abilities that make it so challenging - and satisfying - to work out the solutions. You can only have one cube of one colour at one time, and you can't change the colour of squares beneath cubes already in position. That means you need to twist your brain into cube-shapes to work out the order and timings of puzzle solutions. When there is an element introduced that feels more powerful, such as the magnets, these only serve to make it feel like you're breaking the system in some way by discovering methods the designers never intended. You're not - these are the only available solutions to the puzzles - but it still feels fantastic.

I just adore puzzle games, and figuring out a particularly tricky room in QUBE 2 gives me a sense of joy that I struggle to replicate in real life.

Also, it reminded me of Portal. A lot. Did that come across?

Yoku's Island Express

Matthew: I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: I’m really envious of Yoku. He lives inside a giant pinball table, which means the world does all the hard work for him. Imagine just sitting there as flippers bat you towards your destination, or coasting on metal rails from one side of town to the other. Yes, you’d live in constant fear of The Abyss, but have you read the headlines recently? The threat of falling into an ambiguous pit can’t be any worse than [insert whatever shitshow you’re currently dealing with]. Regardless of whether Yoku’s Island Express is a great game, it’s a solid pitch for where we should be taking our infrastructure.

Luckily, it is a great game. One that makes a clever connection between pinball and exploration. What are pinball tables, after all, but landscapes dense with secrets that you unpick by squeezing the ball into crannies or opening new routes by exploiting obscure rules? Villa Gorilla’s magic touch is splitting the world into a network of smaller tables. It’s pinball for people too impatient for actual pinball, giving a constant rush of new challenges, while still channeling that core satisfaction of nailing the perfect shot. It also has lots of fruit pick-ups that plink and plonk happily - as any serious GOTY contender should.

On top of all of this there’s a layer of Metroid-y thinking, as new abilities open new routes and reinvent previous paths. I’m very fond of the slug hoover, which is not something I expected to write this year. One of my favourite things in this kind of exploration platformer is uncovering a map screen and seeing a vast world unfold in cross-section - that this map connects into one massive pinball table is doubly pleasing. Both Metroid clones and pinball games are hard to get right, for Yoku to tackle them both, and find so much interesting interplay between the two, made this the most pleasant surprise of the year.

Graham: I associate pinball tables with dank bars, dilapidated seafront arcades, and the crushing regret that comes after three balls have plummetted beween the paddles, taking your money with them. Yoku's Island Express is the antithesis to all of these things, set as it is on a sun-kissed island of happy creatures, plentiful fruit, and playful rhythms. Here, pinball isn't about grafitti art and skulls on fire, but about the fun and freedom of pinged, spun, and shooped along rails and around a colourful world.

I was convinced to play it by its trailers, so I'm going to put one here in case it does the same for you:

What I was grappling with in my Yoku's Island Express review was that I thought Yoku was probably a very good game rather than a great one. I still think that's probably true, but I found myself compelled to celebrate it at the end of the year anyway. There are few games that offer such easy access to joy, and I could use a few more of them.

The Red Strings Club

Matt C: Would I want to visit The Red Strings Club? It’s a classy place, with gorgeous piano tinkling and and drinks that put you in touch with the roots of your soul. That’s no exaggeration - the bartender plays his patrons like an electric fiddle, nudging their mental states towards the answers he seeks. He’s an information broker, and most folks know something about the conspiracies that whirl outside his doors.

Those conspiracies involve brainwashing, AI and cybernetic implants. Shadowy figures are bent on rewiring humanity to eliminate prejudice, depression - and inevitably, freedom. Hang around the club for long enough, and you might start to think they’re onto something.

That’s largely because the Red Strings plays host to one of the most interesting characters I’ve ever met. Akara is the world’s first ethical android, and she wants you to know about it. Maybe drugging your customers is an ironic necessity when unravelling a plot about neurological manipulation, but there’s no way that’s going to pass without comment.

It’s a game about questioning assumptions, and not just when you’re playing detective. It’s the most explicitly philosophical game I’ve played since the Talos Principle - and that mostly involved absorbing dialogue rather than participating in it. Akara quizzes you after every encounter, testing both your intuition and your moral compass.

Technology can set that compass spinning. Who’s to say that ridding the world of mental anguish is an evil act, and who’s to say that it isn’t? Should we change what it is to be human, or should we be left free to suffer? There’s more philosophical meat here than at one of Kant’s dinner parties.

I wrote my university dissertation on whether we should turn to AI for moral guidance, and struggle to convey the thrill of playing a game that asks the same question.

Alice Bee: Matt will definitely have written about philosophy this time. The Red Strings Club is fabulous. My favourite thing about it is that it’s all hands on. Normally when I play something that’s about the terrible advance of technology, it’s about how humanity becomes removed from actually doing the stuff that gets did. You just press a button and your computer does whatever the queued action is.

Because it was the sort of upbringing I had, we used to go to the RAF Fairford Air Tattoo most years, and one year we were talking to an American pilot, who flew one of those big transport planes. He said that the crew used to be bigger, but as technology got better you needed fewer people to fly a massive plane. And he didn’t mistrust the technology, he just felt a bit safer with more people on board in case the tech stopped working. Like when you enter a signal dead spot and can't access Google Maps and really wish you had someone who knows the area because you have no idea where you are and you’re pretty sure you’re going to die.

The point of that story is that in The Red Strings Club technology is super advanced but still made by hand. In the first section of the game you’re an android, inserting implants into people to change their lives. One of them can somehow give them more followers on social media. The people come through on a production line, hanging on a conveyor and totally naked. It’s very impersonally personal. But the implants themselves, that have the power to change a person’s core beliefs and personality, are crafted on a lathe, like pottery. Your job is to make them into the right shape. As if we figured out the secret to life-altering technology, and it is: this specific angle combined with this curve will make you not care about the opinion of others.

This sort of thing runs through The Red Strings Club like some kind of long thread. The actions of people are tied up in technology because, obvs, it’s what we do with technology that makes it good or bad. Unfortunately a lot of people are shitheads.

Katharine: Those cyberpunk pottery sections Alice mention above are my favourite parts of The Red Strings Club. You've just hacked an android responsible for sculpting personality modules out of clay to fix the problems of would-be clients. Or at least it looks like clay. Whatever futuristic material you're actually dealing with, you sit down at a crafting wheel and slowly ease different shaped tools in and out of chunks of biomatter stuff with your mouse to create the desired template.

Now I know nothing about pottery and have never 'thrown' an actual pot, as they apparently say in the pottery biz. But it's also something I've never done in a video game before either. It's oddly therapeutic, clicking your mouse real fast to whirr up the wheel while moving it from side to side to mould it into the correct shape, and I don't think it would feel nearly as satisfying or tactile to perform using a controller, for example.

It's a shame there isn't more of it, really, especially when the entire act is so fundamentally tied to your mouse, and therefore your PC as a whole. In fact, I'd happily play a game that was just cyberpunk pottery, perhaps against the clock or with even more tools at my disposal to make even more outlandish sculptures. Alas, what I thought was going to be a tutorial for something more complicated later on in the game like the bartending sections ended up being just that: a one-off module-making session.

Still, despite its brevity, this is anything but a throwaway mini-game. Your actions here and the modules you choose to install do in fact have a lasting impact on what happens later in the game, and it's just another thing that makes The Red Strings Club stand out as far as I'm concerned - although if anyone does know of a good pottery-making game, please do point me in its general direction. I promise I won't use it to hack your personality in the process.

The Hex

Katharine: Not content to send up one genre of gaming, The Hex takes aim at practically every type of game going, from platformers to RPGs, top-down shooters to turn-based strategy and everything in between. It's a both a celebration and gentle probing of what makes games tick, and the best thing about The Hex is that it lets you break and hack every single one of them in order to solve the mystery of why its extensive cast of characters have all been called to a spooky bar in the middle of nowhere, and who will be the one to commit a horrible murder that same evening.

It's a brilliant conceit - I particularly love the idea of a fighting game character 'breaking free' from their eternal face-mashing to become 'OP' as the kids say and get banned from play - but one of The Hex's greatest moments is when it appropriates your own Steam friends list in order to make fake user reviews for its opening platformer sequence.

You play as Super Weasel Kid, a mash-up of Mario and Sonic that appropriates the former's jumping antics and newly spiked goomba enemies and charts the latter's descent into 'too cool for school' territory until he fades into irrelevance. You can see his demise play out in the 'games' themselves, each sequel getting further away from what made it good in the first place, but there's also something inherently cheeky and hilarious watching other real people you know react to Super Weasel Kid at the same time, especially when it's fellow RPS-ers Brendy and John singing his praises before tearing him a new one moments later.

It also gave me pause, though, reminding me what terrible monsters we can be when reviewing games, both as critics and consumers alike, and how difficult it must be for devs to please the unrelenting tide of the masses who demand this that and the other ALL THE TIME. Few other games have made me take stock of how we interact with this most favourite pastime of ours this year, and that alone deserves to be praised and absorbed by as many people as possible.

John: I love the idea of The Hex having its official ending in another game more than I like the idea of actually having to go find it. But I still love that it did it. And I love that having finished the great game, I've still got so many questions. It's a game where you just want to find someone else who's played it, and then ask them everything they're bursting to ask you.

Looking back on it feels less like a game, and more a collection of memories. Which is pretty apposite, I suppose, since so much is told as individual characters' flashbacks. Jumping through a platformer made of negative Steam reviews, punching my way through a beat-em-up that slowly turns on itself, and best of all, those turn-based strategy sections where you use game cheats like magic spells. (I still so desperately want someone to realise that idea as a full game.)

It certainly had far too much of its rather saggy RPG section, but then I really didn't mind when it was in the same game as one that had me laugh so loudly through a hand that had gone to my mouth in shock.

Daniel Mullins has such a smart approach to games-as-games-criticism, somehow managing to make something that avoids belly-hole introspection, yet so searingly and often scathingly presents both gaming, and the culture surrounding it, as a satisfying game itself. I still think he did this better with Pony Island, but The Hex is a wonderful companion. I really cannot wait to see what he creates next.

Alice L: How can a game be like so many games you've played but at the same time be nothing like any game you've ever played? I dunno, but The Hex nails it. There are a few moments that linger for a little too long, but mostly it's snappy, intriguing, and just asking for you to play more. It enables you to reminisce over games you’ve played and loved, and be surprised by something new all at once.

The familiarity of it is enticing and keeps you hooked, but it was the initial chatter surrounding The Hex that pulled me in. It's hard to say a lot about it without spoiling it, and the only reason I decided to dive in was because of the mystery surrounding it. I’m so glad I did.

Battletech

Alec: Hey, 24th April 2018 Me, you won't believe what just happened...

Battletech made a poor first impression on me. I said so, in public, because that's my job'n'that. Enough people I respect (and a lot of other people with all the warmth of a spent, rained-filled can of Red Bull that spent the entirety of November lying in a gutter in Tromsø) had a more positive reaction to it; I'm old enough and ugly enough to know that refusing to hear other points of view - whether or not they adjusts my ultimate opinion - is Angry Young Man-ism, prioritising screeching righteousness over useful understanding. So I went back, I worked harder to understand what this turn-based strategy game had explained about as well as a Sherbet Dib-Dab-addled toddler teaching quantum physics, and, yeah, I got it.

And here we are today. Here I am today, having singlehandedly made the case that Battletech should be one of RPS' bestest best games of the year. (No other rotter on staff has played it yet). Suck it, 24th April 2018 Me.

It's a line I've used before, but the true meaning of Battletech is not a bunch of big robot suits firing lasers at each other until one of them falls over - it's interplanetary Pokemon.

First time around, I was playing on the basis that I had to win, by hook or by massively self-destructive crook - essentially, trying to pummel the enemy into submission before they could do the same to me. Traditional, XCOMish tactics didn't seem to get me very far; it seemed to be an endless war of hitpoint attrition, like two hippopotamus slapping each other with banana leaves until somebody decides to have a nap.

But then! No, don't do that, you fool. Go for the legs, you fool. Not, not even the legs, not any more - go for the side torsos, the ammo stores, the difficult headshots. Rack up pilot injuries rather than reducing your 100-ton trophy to rubble. Kill the meat and spare the metal.

That's how you build an army of steel. That's how you play Battletech. It's a slow game for sure, but the way I play it since The Revelation doesn't feel slow, at least not now there are animation speed controls patched in too. Taking down (and then taking home) an enemy mech is a co-ordinated lightning strike on specific body parts, from specific angles, where once it was like pelting the side of a bus with Haribo.

There's so much I'd change about Battletech if I could; the presentation, tone and storytelling is about as a lively as a night on the tiles with Iain Duncan Smith (even if it is olden tabletop source material appropriate), the tutorial as helpful as a cat trying to explain existentialism, and those headline-grabbing mechs themselves would struggle to give a VHS machine from the 1994 Littlewoods catalogue a run for its money in the 'fabulously imaginative technology' stakes.

I can't stop playing, obviously. The core loop, the essential realisation of precision-subsystem-strike combat, is so well-realised, so compulsive and so satisfying, that I don't even see the sea of brown'n'grey any more. I see my plan. I see my trophies. I see glory.

Better still, the recent Flashpoint DLC liberated Battletech from its bafflingly pro-monarchist, slow-motion shrug of a plot, transforming it into the long-term, delightfully endless game of freelance, iron-clad mercenary work it truly deserved to be. Battletech will be one of the longest-term residents of my hard drive in quite some time.

Jazztronauts

Alice O: Jazztronauts sends us ram-raiding Steam Workshop levels in an interdimensional tram to steal furniture, fixtures, fittings, trash, and even walls at the behest of cats who live in a dimensional nexus of a bar. Now that's a video game premise.

The true wonder of this mod for Garry's Mod is that, aside from the hub and a bit of story framing, the whole game draws from maps and characters uploaded to the Steam Workshop for other purposes. A giant telly in the bar flicks through random levels, showing only the name and thumbnail, then when we like one we lock it in, hop aboard the tram, and head down the windy road between worlds, downloading the level automatically.

When we arrive, it's time to steal. Whacking certain types of bits in the level with our baton will summon magical scientsits to suck it up and whizz it away. Tables, chairs, crates, lights, lamp posts, trees, plants, food, trash, vending machines, rocks, telephones, doors, microwaves, kettles, sofas... depending on how the level is built, we can steal all sorts of things. Eventually we can buy upgrades to even steal walls, ripping them out with a groaning shudder to reveal the pink and cat-filled glimmering raw fabric of the universe. This is: 1) great fun; 2) all sorts of daft; 3) a delightful ripping-apart of the reality of games.

Jazztronauts revels in how fake this all is. A 'Mewseum' in the hub teaches the basics of how Source levels are built, teaching what we can and can't steal, and houses a menagerie of the NPCs we yoink. Video game levels are fake as heck, and Jazztronauts wants us to tear them apart. We get tools to steal more, steal faster, and warp through walls. The paper-thin reality is shredded but peeking behind the scenes only makes it more delightful, getting to explore places we weren't meant to see.

While the cats can be a bit sarky about some levels, Jazztronauts delights in how damn weird player-made levels can be, the range of things players want to see - and the range of skill they have to make them. As a fan of mod readme files, I've hugely enjoyed ram-raiding random levels. Cities built for roleplaying modes, Counter-Strike levels, recreations of real-world houses and schools, test levels, bugged levels, race tracks, RTS maps, places from Star Wars and Harry Potter and Spongebob Squarepants, waterparks, playgrounds whose purposes I cannot fathom... I adore this way of flicking through the Workshop.

Flashes of other players' reactions appear too, with Jazztronauts drawing random comments off a map's Workshop page to appear on monitors in the bar and adorn the side of the tram. I laugh every time I see someone furious, baffled, spamming creepypasta stories that I must read to the end or I will DIE, or mourning the closure of a swimming pool.

Jazztronauts also captures that classic "How do I make this damn thing work..." often felt when trying to play mods and custom levels. While it'll download the level automatically, the map won't necessarily come with all the resources you need, sometimes leading to pink and black checker textures on a surface or a model replaced with the word "ERROR" in metre-high red letters. In Jazztronauts, this doesn't ruin a level, just makes it more psychedelic and strange.

Perhaps you'll visit famed magician school Hogwarts and return home with only scrap wood, some fruit, and several hundred error messages.

Oh, yes, I didn't mention all that. When we're done with a level, having collected randomly-spawned gems and stolen our fill, we call the tram to pick us up. It will punch a hole in the level, smashing through dynamically in a way that still makes me smile. Then, back at the bar, we get to pull a lever and have our haul totted up as it rains from a chute like the boobie prize on a game show. This, obviously, is great.

And I shouldn't forget that the framing of these crimes is wonderful. The writing is sharp and funny, the cats varied and delightful, and I'll always chat with everyone (yes, it's kinda a visual novel sorta thing too) when I return to the bar.

And it's ridiculous shenanigans when playing cooperatively with pals.

Jazztronauts reveals the artifice of video games in a fun and clever way while celebrating the enthusiasm and absurdity of people who build things for them. Video games are wonderful and daft and so are we all.

Dragon Ball FighterZ

Dave: When I first played the beta for Dragon Ball FighterZ and had a starting lineup of Goku against Frieza on Planet Namek, I was treated to an in-game recreation of the famous scene in the Dragon Ball Z anime where Goku first becomes Super Saiyan. It’s not the only time the game directly recreates the series, as finishing the fight with Goku against Frieza on a destroyed Namek with a heavy attack gives you the climax of that same fight, and even relatively minor characters Yamcha and Nappa have a fun Dramatic Finish in the Wasteland stage. But seeing that scene, beautifully rendered in the game and given a modern shine, brought back memories and gave me goosebumps.

I’m not massively into anime. For every My Hero Academia out there where I enjoy the premise, there’s another like Attack on Titan that I just find impenetrable. Don’t get me started on why the very thought of Sword Art Online brings me out in hives. So it was a surprise to me that I became a fan of the most Shonen of Shonen Jump manga - Dragon Ball Z - when a friend forced me to watch it.

Dragon Ball FighterZ is not just a pretty face however, as it has everything that I’d hoped for from Marvel vs. Capcom Infinite but which never materialised. The Dragon Ball FighterZ roster has the characters I was largely expecting, for example, but each one has movesets that fit their character. Piccolo uses his stretchy limbs, Frieza has the destructo-disc that comes back and can hit himself if he’s not careful, and so on.

It mimics the anime in heavily featuring screen-wide beams of energy, but it also has a combo system that’s accessible for those who want to get into it and challenging enough for experts to find new ways to get that extra slither of damage. This in turn makes the 3v3 fights frantic. Dragon Ball FighterZ is a lot more technical than any of the Dragon Ball Z tie-ins that have come before it, and more fun for it.

If I had one thing to knock against it, it's that the story mode drags on way too long and feels like some weird fanfiction someone made with all their dream fights in one place. That said, taking breaks from the story mode to either square up against others online, or have a run through the challenging arcade mode more than makes up for it.

For a game that’s as much fun as it is, the number of players on the PC version is criminally low. Presumably there are more players to be found on the console versions of the game, which remain the traditional home of fighting games. However, even if you don’t ever fancy putting up your dukes against another player, Dragon Ball FighterZ has more than enough stuff to play around with.

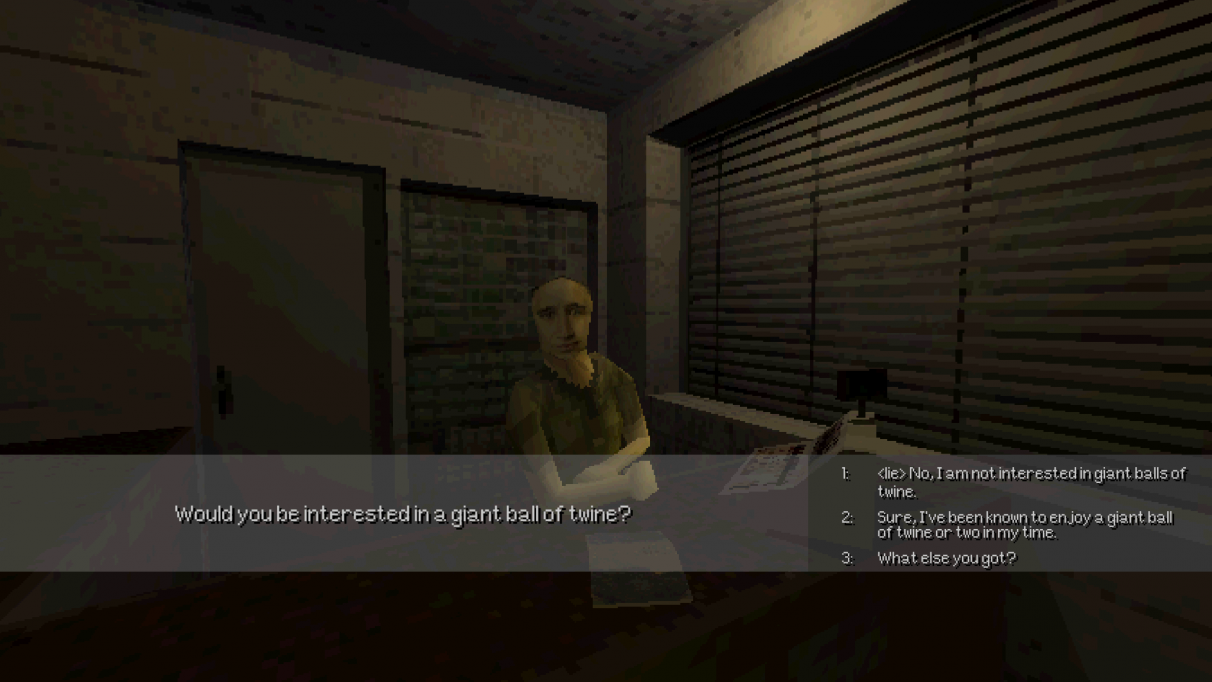

Paratopic

Alice O: Chin up, friendo. You're transporting cursed video tapes which are narcotics at best and a dreadful power at worse, you're in hock to some real shady figures, the city is near-deserted, crows peck at bodies in the streets, and The Man is on your back, but it could be worse - yours could be one of the other two stories this first-person vignette 'em up jumps between.

Paratopic ties together three overlapping stories from three people (or... does it?), a hiker, a courier, and an assassin. We jump between them in time and space, often with only subtle hints that we've changed. Sometimes we walk, sometimes we drive, sometimes we chat, sometimes we... ah, you'll see. It's a bit Thirty Flights Of Loving though at a less hectic pace, especially in scenes where we can linger or chat.

I do like chatting to people. Paratopic's dialogue is often sharp, with menace, humour, and chat all coming across well. I especially like that one option to say we're not interested in a giant ball of twine is explicitly marked as a lie; a twist of a familiar branching dialogue tool shows us more of who we are. I like the garbled Killer7-ish voices as well, especially while listening to the talk station on the car radio.

OH. I LIKE THE DRIVING. Driving through this sinister city is splendid.

I dig the 90s 3D look too, another edge of unreality, and it looks real pretty at times. Having wee doodads to fiddle with around the game--stubbing out a smouldering cigarette, squirting ketchup, and of course a camera to snap away with--is grand as well. Love those fiddlebits.