How Teardown made a great game from destruction

If you unbuild it, they will come

Games about destruction tend not to do the whole destruction thing very well. Put it this way: for years Red Faction has been the banner for destruction in games, despite its most recent instalment releasing nine years ago and its core being rather more about shooting than destruction. While you can destroy lots of things in Red Faction, there’s not much of a game in it.

Thankfully, we now have a new banner destruction game: Teardown, a game in which you can destroy pretty much everything. But Teardown’s serendipitous and difficult journey from tech tinkering to release taught lead developer Dennis Gustafsson something important about the whole idea of letting players demolish stuff. “There’s this expectation that more destruction in games is always a good thing. But actually, it’s really, really hard to design something around a fully destructible world.”

What you play today is the result of many different prototypes made in Gustafsson and partner Emil Bengtsson’s often fruitless-seeming attempt to find a good game in destruction. Teardown has been a driving game, a survival sim, and a stealth game. It’s featured giant spiders and taken on various different flavours of the heist game it finally became.

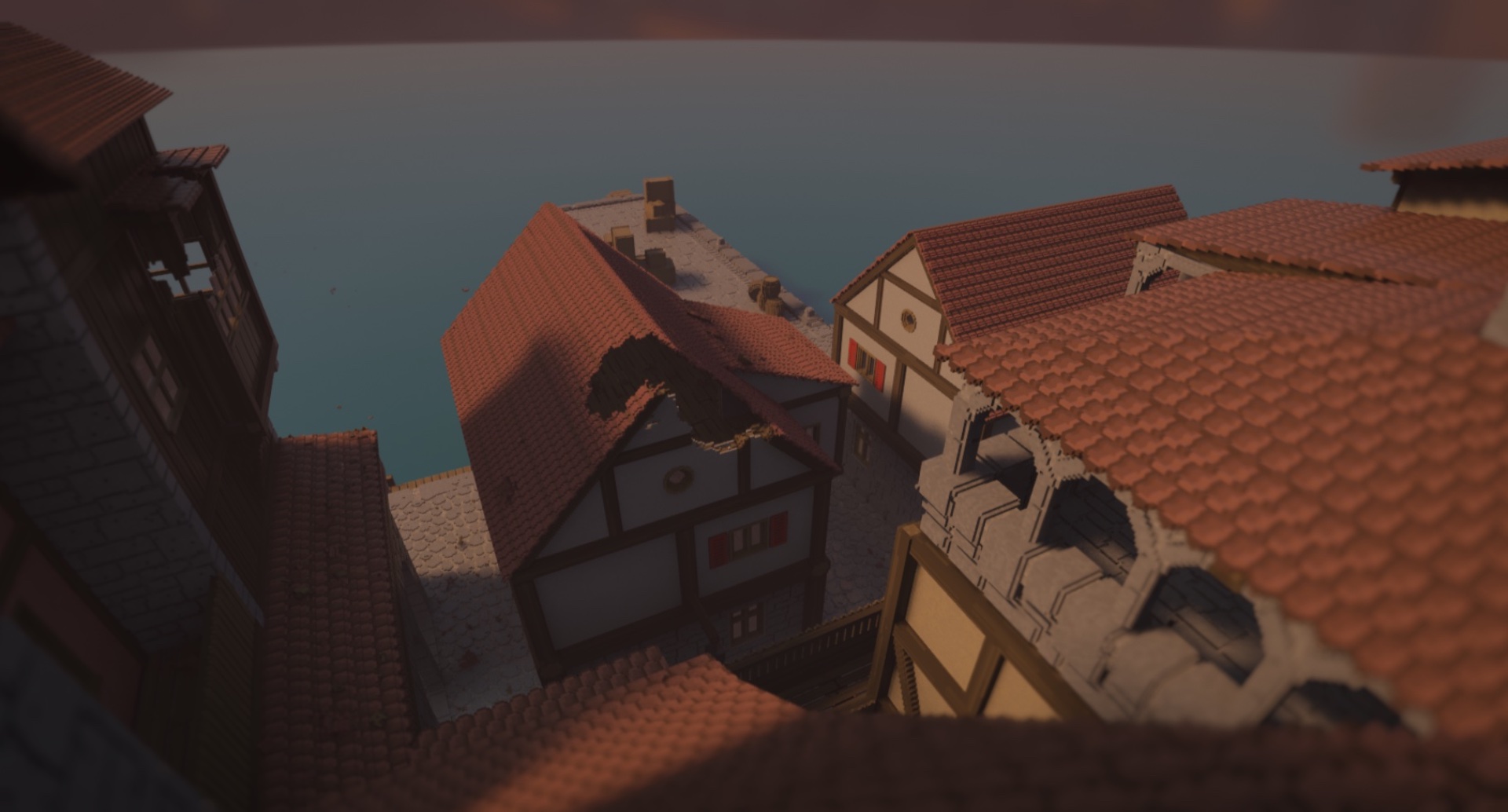

And it didn’t even start off as being about physics destruction, despite Gustafsson having started his career at physics middleware companies and his highest selling game (so far) being the 150-million-player mobile-based physics puzzle game Smash Hit. Instead, Teardown flickered into life as a ray tracing experiment. Entranced by the look of realistically lit voxel environments made in Magicavoxel, Gustafsson had started messing around with voxels, experimenting with realtime ray tracing that was made possible by the geometric simplicity of boxy scenes.

Those voxels got Gustafsson thinking. Physics destruction with polygons is difficult, partly because arbitrary geometry makes it hard to calculate collision detection. But nice square blocks? Voxels made the technical fundamentals a lot simpler, and soon enough he had a sandbox up and running in which you could run around and smash up a voxel world.

“Which isn’t really a game,” admits Gustafsson. “But it was a lot of fun, and then I teamed up with Emil, who I’d worked with before, and we tried to come up with a game idea for this setting, this world where everything is destructible. And that’s where the challenge began.”

The reason why Teardown is great, and why Gustafsson and Bengtsson had such a torrid time in making it, was that they swore from the outset that they’d avoid one of the key pitfalls of destruction games: the way destruction is used as a visual effect without much bearing on the game itself.

This commitment immediately wrote off their first prototype, a driving game in which you’d smash into things and see them falling over. ”I never thought it really worked,” says Gustafsson, “Because when you smash into something you can see it breaks but you don’t use it for anything and you don’t see much of what it causes because you’ve already swooshed by when the thing settles.”

So over several months they turned to making a series of stealth game prototypes. You’d think that stealth wouldn’t gel too well with a concept based on smashing stuff up and, sure enough, that was a problem. Enemies had to be made very insensitive to sound to accommodate the destruction, and this presented all kinds of issues that Gustafsson and Bengtsson never really solved, whether the enemies were swarms of spiders or guard robots.

More than that, though, having enemies in the game got in the way of the fun of breaking things. Just when you wanted to experiment or perform a spot of precise destruction, they’d show up and derail you. Yet within this problem lay an idea that would come to define the philosophy behind Teardown – not that Gustafsson and Bengtsson realised it at the time. They instead moved on to develop another prototype, this time based on a heist, where the challenge was about getting to the things you had to steal.

“The problem with that, of course, was that when everything is destructible, the task becomes almost trivial if you’re given a lot of resources,” says Gustafsson. You’d blow up the wall with your bombs, grab the valuables, done. He and Bengtsson didn’t want to restrict the number of bombs you’d have, but they tried placing caches at specific points on the map so you’d have to go and get them before pulling off the heist.

“But it never really took off because the fun of the game disappeared when you were so restricted that you couldn’t do anything,” he says. “If you’re not given vehicles and tools to do destruction it’s more just a regular game, and then once in a while you can place a bomb and see the effect. We wanted more freedom than that.”

Moreover, Gustafsson knew that providing that kind of freedom limited the number of obstacles he could put in the player’s way to add challenge and shape to a scenario. He had elevation: how high up would the objective be? Water could slow players down or deny access. Distance imposed time limits on them. He could also place indestructible objects in the world but he didn’t want to, because they’d be frustrating and potentially introduce confusion over what a player can destroy.

“It was a very, very frustrating experience, because from a design perspective, a fully destructible world is terrible to work with because you can’t put any restrictions on the player,” says Gustafsson. He was sure that somewhere across all these prototypes lay a game he wanted to make, but after seven months of searching, he was beginning to think they weren’t going to find it. Bengtsson came off the project, but Gustafsson kept plugging away, in part to continue developing his engine’s physics and ray tracing, and in part because he just couldn’t face abandoning the whole thing after spending so much effort on it.

Then, a breakthrough. Gustafsson knew the game was at its most fun when he was free to walk around and tinker. Remembering the way spiders would derail him as he was trying to indulge in a little pinpoint destruction, he understood that the game couldn’t really have any enemies or dangers spotted around the world, and he came up with the idea that serves as Teardown’s heart: two phases.

In the preparation phase, you’re free to do what you like for as long as you like. This unimpeded period of experimentation and play is when you plan the heist and prepare the ground for it. Then, in the second phase, which usually triggers when you steal the first object, a countdown begins and the game changes. Now your plan is in action and success is down to how well you’ve prepared and whether you can pull it off.

Why is the key pressure Teardown imposes on you in the second phase usually a countdown? For Gustafsson countdowns seemed to fit the heist theme, but he tried some other ideas, including setting the target in a cave network deep underground which would start to fill with water when you collected it. But the pure timer won out.

“I think that from a game design perspective, timers are almost always considered a bad thing,” he admits and, in fact, he agrees. But it became apparent that giving the player choice over when to set it off negates a lot of of the frustration that comes with being given time pressure. “It never comes as a surprise. You don’t start the heist until you decide to.”

Teardown had one final creative leap to make before it became the game it is today. Gustafsson’s first heist levels were long corridors along which the player would have to proceed, grab the loot and return the same way to return to the getaway van. They had one target to grab and a set distance to cover.

But as he and Bengtsson, who’d rejoined the project, designed maps, they discovered that the obstacles available to them – elevation, distance, water – really weren’t giving much to work with. But what if players had to steal multiple targets? And what if they were scattered across a wide level, rather than being located at the end of a long corridor?

The game suddenly opened up, presenting a broad physical and temporal space for creative destruction. Bengtsson and Gustafsson had found their game.

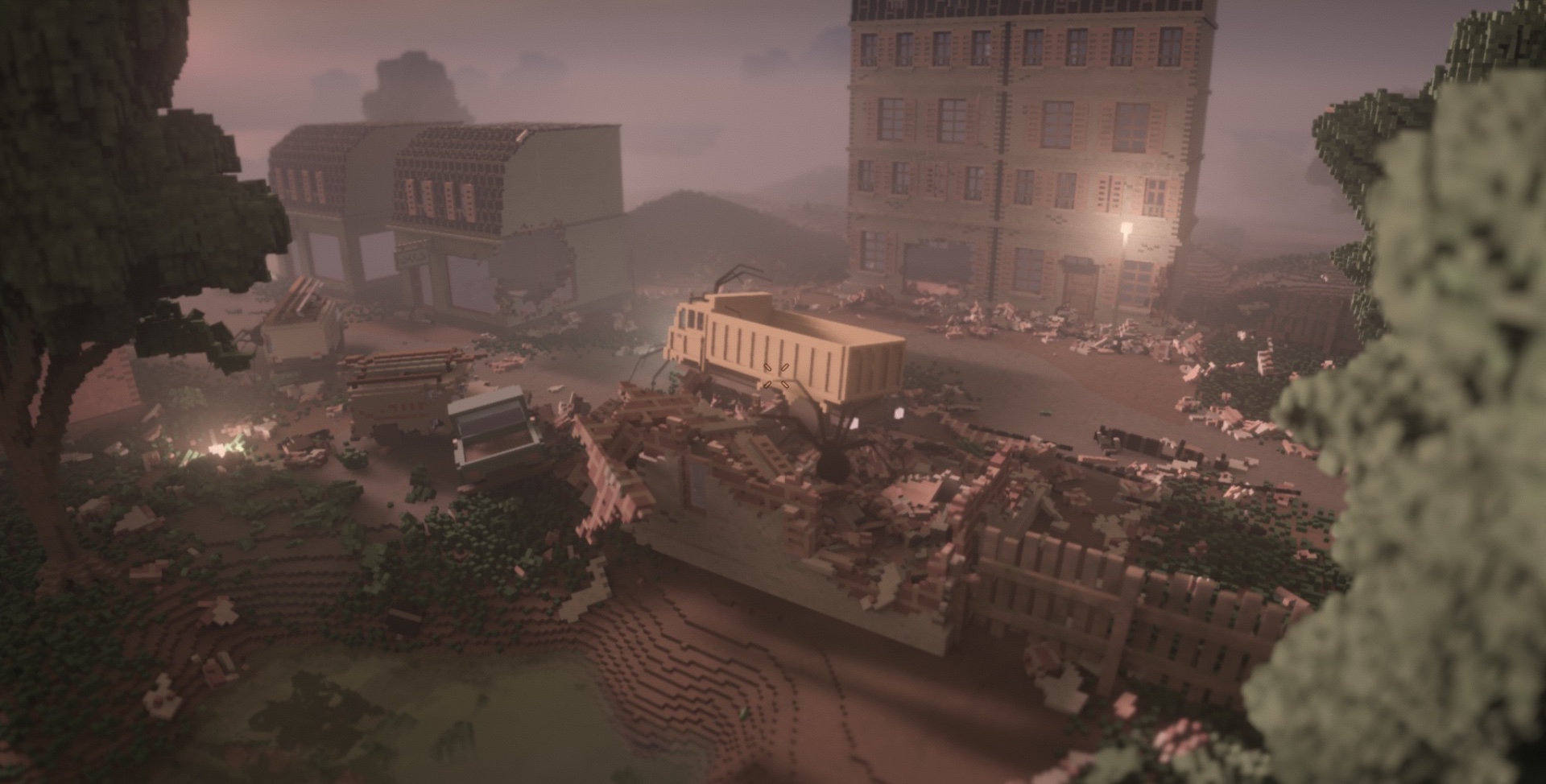

Of course, since release in Early Access, it’s turned out that the most popular levels in Teardown don’t involve the countdown. Players’ favourite levels are the one in the Hollowrock Island map, in which a helicopter gunship appears when you trigger the second phase, the one where you’re dodging lightning strikes while stealing paintings, and the ones where you’re demolishing buildings.

So as work continues on the forthcoming second part of the game, Bengtsson and Gustafsson will focus on missions without countdowns. “But it’s also hard to say, because usually when a game has a lot of missions of one type and a few outsiders, you tend to like the outsiders more. But if you fill the game with the outsiders you’ll like the others.” Gustafsson laughs. “So I think we’ll try to find a better mix.”

For him, though, Teardown’s at its best when it’s against the clock. “I really like the time-based heist missions, because I enjoy this optimisation aspect, of going back to perfect things.” It’s a preference which seems to speak about his determined attitude to game design, one which found something that no one had managed before: a great game in destruction.