Terry Cavanagh on why he believes Dicey Dungeons is his best game yet

Loaded questions

Terry Cavanagh is known for making difficult games, including the likes of Super Hexagon and VVVVVV, two tough-as-nails gauntlets that challenge digital dexterity and reaction speeds. They're crucibles where the sting of failure is treated by the balm of an instant restart. They're not, notably, deckbuilding roguelikes that revolve around dice manipulation. That would describe Dicey Dungeons, Cavangh's latest and (according to him) greatest game.

Back at GDC in March, I got the chance to ask him about it. "People hate dice and randomness," I said. "Why did you make a game about dice and randomness?"

"It's not like I'm especially into dice!" he objected. I'd unintentionally put Cavanagh on the defensive, my tongue perhaps too hidden inside my cheek. Still, it's unusual for a videogame to revolve around a board game component some might (mistakenly) view as archaic. Plus, it turns out, he is totally into dice.

"So this started as a jam game at some point last year - I really wanted to make a deckbuilder inspired by Dream Quest. Obviously that's a very figured-out genre, so I thought about ways I could do something different, and dice seemed like the right direction."

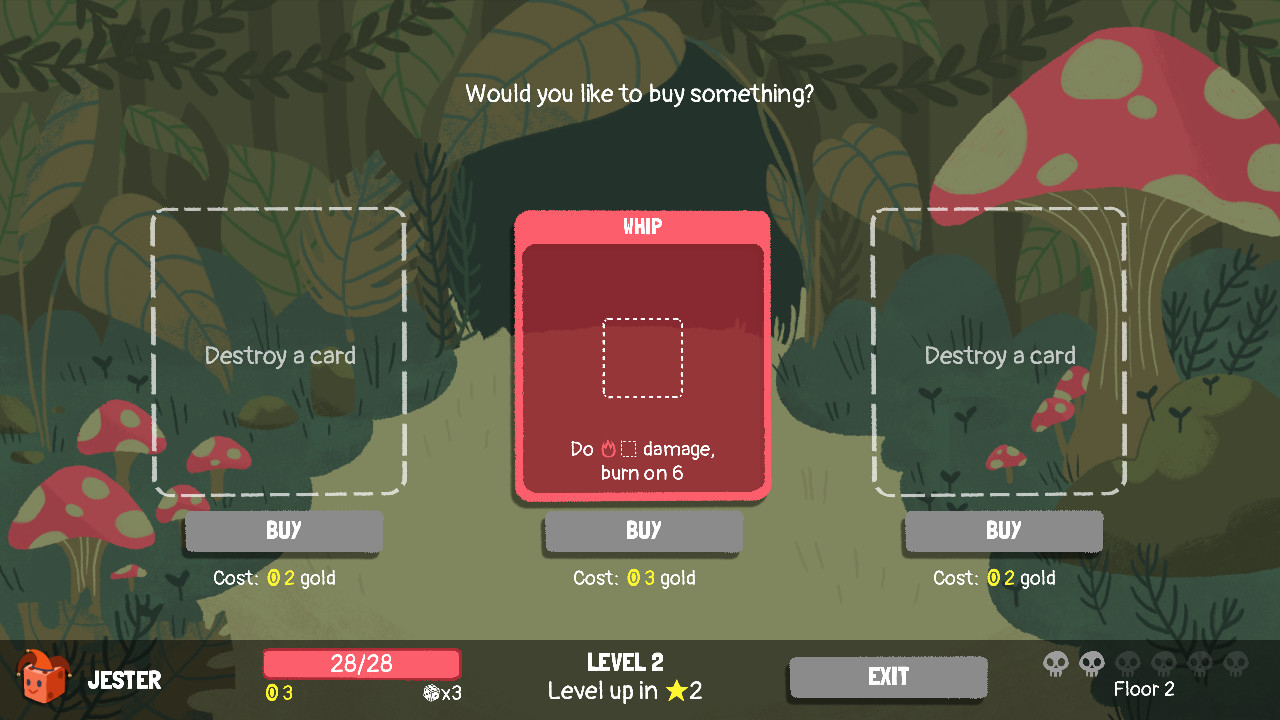

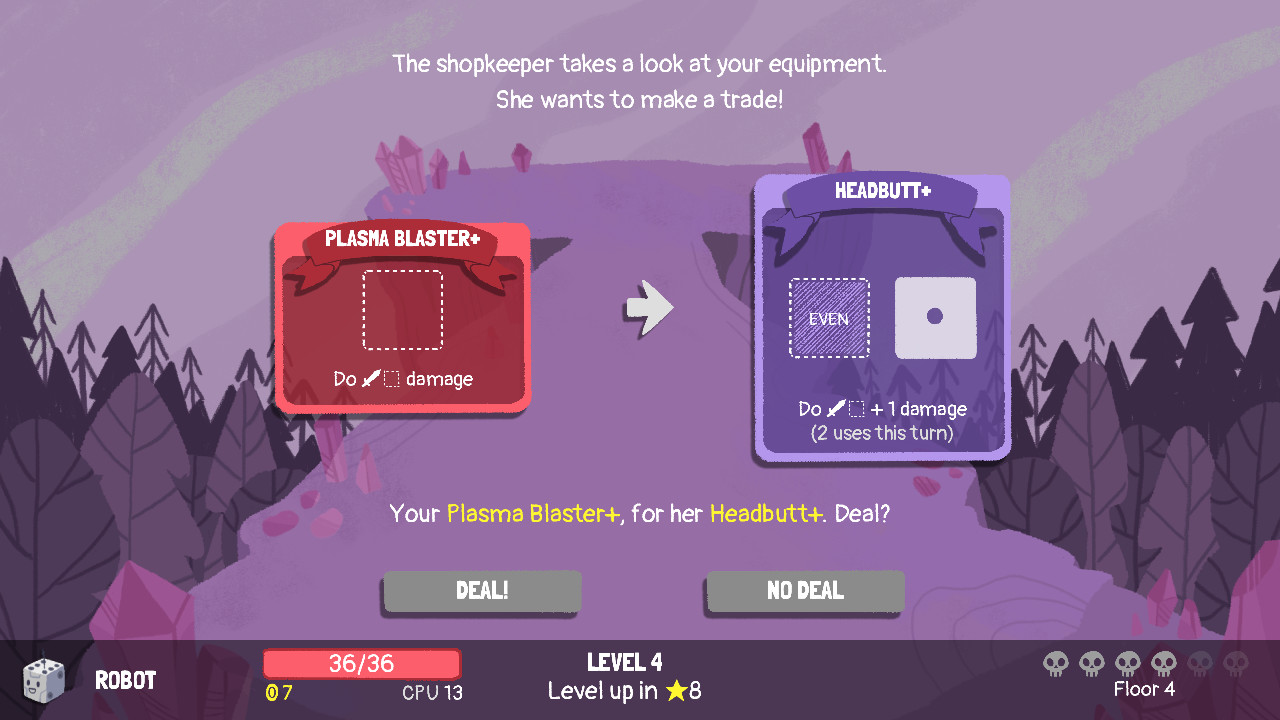

Dicey Dungeons is about rolling dice, giving them filthy looks, then massaging your results into something more palatable. A six might be useless to a Thief wielding a dagger that you can't use with any number higher than a four, for instance. That's when the Thief gets to break out their trusty lockpick, and split that six into two lower numbers. You accrue more equipment over the course of each run, and there's often not enough space for all your gadgets. It's a dice-driven deckbuilder with tools instead of cards.

"It turned out that combination really, really worked, which I didn't expect. You could say I stumbled into it, but I've come round to loving dice and the way they let you think about randomness in this very comprehensible way. Anyone can see really simple odds. Say you roll a one and a two, you can go 'oh if I re-roll this it'll probably be higher'. You can immediately do that in your brain without too much stress, which is a fantastic thing."

I don't hate dice. Deployed correctly, they can be a powerful driver of interesting decisions, and Dungeons is testament to that. I've played multiple early builds, each time returning to a game that's built on the potential of some impressive initial scaffolding. For sure, that's how Cavanagh sees it.

"The core worked from day one, that's what made me so excited. Once I had that, working on Dungeons has just been having a spreadsheet and adding a line when I think of a random thing, and that [immediately] shows up in the game. It's just a constant stream of adding stuff I'm really excited about, because there's so much room to explore."

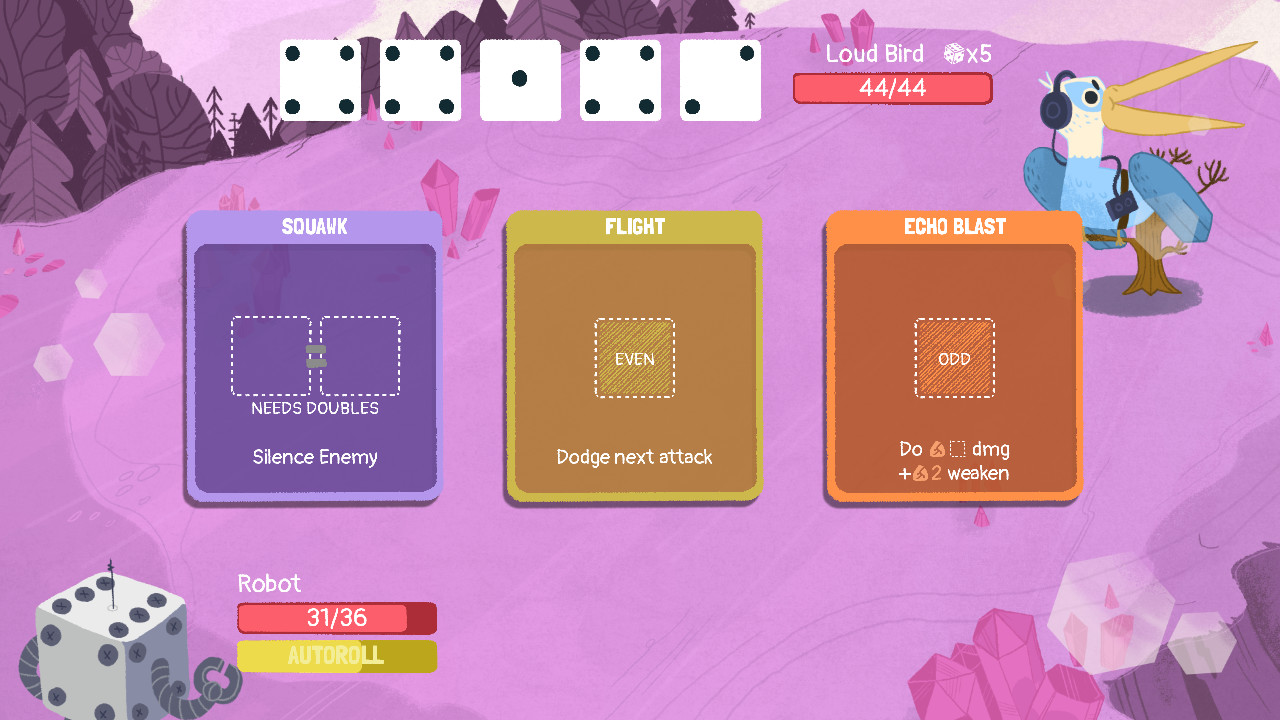

Cavanagh's talking about the six different characters, who all begin the game with different abilities and specialised equipment. That Thief can nick his opponent's tools, while the Witch (Cavanagh's favourite) has a spell book that builds up over the course of each fight. On top of that, each character has six different modifiers.

"Some of those modes are so different they're almost different characters", Cavanagh told me. "There's a robot mod where it works in reverse. So the usual robot rules are about gambling for more dice: when you exceed a certain total you lose all of your equipment. You're playing a game of blackjack to get the resources you need to attack. But there's another robot mod where there's a panel of dice, and you can request them - but there's a 50-50 chance that a random piece of equipment will just disappear, and you don't know what that's going to be. It's very similar conceptually to the other game mode, but it's completely different to play. There's a tonne of stuff like that."

With dice front and centre, though, losing to random chance is always a possibility. When I asked Cavanagh if he ever thought about the players who'd bounce off after an unlucky start, he told me about the one he'd just met. A starry-eyed Super Hexagon fan, excited to get their hands on Cavanagh's latest.

"They were so enthusiastic", Cavanagh told me, wistfully. "Then they sit down to play it, and the enemy was just rolling sixes every time while they kept getting terrible rolls. He didn't fully understand how some stuff worked and they made mistakes, but... yeah they just had an awful, awful time with the game."

Cavanagh chuckled. "Then he sort of cooly got up and went 'yeah, yeah it's really interesting. Cool. Well, thanks, I have to go to another meeting.' Obviously that's gut-wrenching, but it is sort of unavoidable. Part of me wanted to sit them back down and go 'no, play it this way. It's better if you play it this way!' But that's part of the fun, you have to give people the freedom to fail."

As Star Trek's Picard once opined, sometimes it's possible to make no mistakes and still lose. Cavanagh's keen to avoid that, though.

"It's very important that the game feels fair, and I think it does. I think when people lose in the game it's usually as a result of something they've done - maybe not on the last turn when the enemy got a really good roll, but something they did in the last battle, or when they made a bad level-up choice. There's always something that they didn't do right, and that's what makes the game work."

Talk of fairness within chance put me in mind of the modern XCOM games, where reality gets massaged. True randomness means that over the course of a hundred hours, a player may well miss three 90% chance shots in a row. Except they never will, because at certain points XCOM steps in and spares its players from RNG's excesses. No such system exists in Dicey Dungeons, I found out. "It wouldn't be right for my game. It never steps in and makes things easier or harder." Dicey Dungeons can get away with that, he reckons, because failure is nearly always your fault anyway.

"Maybe an unexpected thing about this game is that it's quite easy. If you lose it's probably because you did something wrong. Getting good at the game and enjoying it, mastering it is a process of figuring out what the best strategies are, thinking through the consequences of your plays".

I had one last question, inspired by the hundreds of hours I've sunk into the best deckbuilding roguelike around. How much Slay The Spire had he played?

Next to none, it turns out. "I feel like the biggest deckbuilding roguelike in the world is probably a game I should avoid playing until I've finished this. Just because I don't want to contaminate my ideas with their ideas. I want to do my own thing, you know."

It's a fair approach, although it has its pitfalls. I pointed out other developers might do the opposite, and play as much Spire as they can. We both grinned through his response.

"I mean, part of me wonders if I've messed up here and I should have done that, because obviously it's very good. I wonder if after I finish Dicey Dungeons I'm going to go play Slay The Spire and think 'oh fuck', 'why didn't I think of that? That's so good.'"

I'm glad he hasn't. Dicey Dungeons could well wind up devouring as many of my evenings as the Spire, and if I'm going to fall down another rogue-hole I'd rather it didn't look like the last.

"Genuinely, I think this is my best game", Cavanagh told me. On the balance of probability, I think he might be right.

Disclosure: Former RPS treehouse-mate Pip Warr did some writing for Dicey Dungeons.